EXECUTIVE SUMMARY

This is my long-awaited child. We do not want to give her away.- Parent, Kharkiv

We believe it is our mission to teach the world how to understand people with disabilities as equal to us all.– Parent, Dnipro Region

Disability Rights International (DRI) and our affiliate Disability Rights Ukraine (DRU) have, over a ten-year period¹, documented the human rights concerns of more than 100,000 Ukrainian children – with and without disabilities – placed in congregate settings and left to grow up segregated from families and society in orphanages, boarding schools, psychiatric facilities, and other institutions.

Most families in Ukraine would keep their children with some support. They need assistance to care for a child born with a disability. And without it, those who end up in institutions, most often live painful lives and die lonely deaths.

It does not have to be this way.

DRI asked more than 500 brave and courageous families living in Ukraine what they are now experiencing during the war and what they need.

The war has worsened the widespread problems families have faced as they struggle with little or no support to raise children with disabilities. In interviews with DRI staff, parents lay out all the difficult challenges and barriers they face.

These interviews provide a blueprint of the change that must occur – by governments, donors, policymakers, caregivers, and communities during the war and recovery process. We must hear their stories and listen to their voices.

Over the years, DRI has documented children living in atrocious conditions in Ukrainian institutions – lack of medical care and food, tied to beds and cribs and left to die. Since the start of the war, DRI’s investigations have shown² that, what was already a dangerous situation for these children, has become a life-threatening emergency. Without the love and protection of families, neighbors, caregivers, and friends in the community and lack of government oversight children with disabilities placed in institutions are suffering increased neglect, and they remain easy targets for abuse, trafficking, and forced labor.

Children from institutions³ are being abducted and sent to russia, while others are being moved to other countries for safekeeping. Some may never make it back to Ukraine, but those who do should never be sent to live in an institution again.

After the start of the war, DRI’s investigation showed⁴ that disabled children with the greatest support needs were largely left behind and remained living in atrocious conditions. And in some situations, alone after staff had fled them.

No child should ever grow up without a family, be it biological, kinship, or foster care. Article 19 of the UN Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities protects the right to live in the community with choices equal to others. All children disabled or not – deserve love and a family. Thus, the CRPD Stated in General Comment No. 5 (para. 37): For children, the core of the right to be included in the community entails a right to grow up in a family.

¹ No Way Home The Exploitation and Abuse of Children in Ukraine’s Orphanages https://www.driadvocacy.org/sites/default/files/2023-10/No-Way-Home-final2.pdf

² Left Behind in the War: Dangers Facing Children with Disabilities In Ukraine’s Orphanages https://www.driadvocacy.org/reports/left-behind-war-dangers-facing-children-disabilities-ukraines-orphanages

³ Stop Abduction of Ukrainian Children https://www.driadvocacy.org/nyt-opinion-letter-russias-abduction-of-ukrainian-children/

⁴ https://drive.google.com/file/d/1STQ3RcDSFFXpeFr5XxkX5ce4Tg_Vz6vR/view?ts=6272f55c

SUMMARY OF FINDINGS FROM INTERVIEWS & SURVEY

No one will tell you what to do and where to go to get services for your child; you have to be very persistent and mentally resilient.- Parent, Dnipro region

DRI has conducted this survey under odious and dangerous conditions in Ukraine– experienced both by DRI staff and those who agreed to participate.

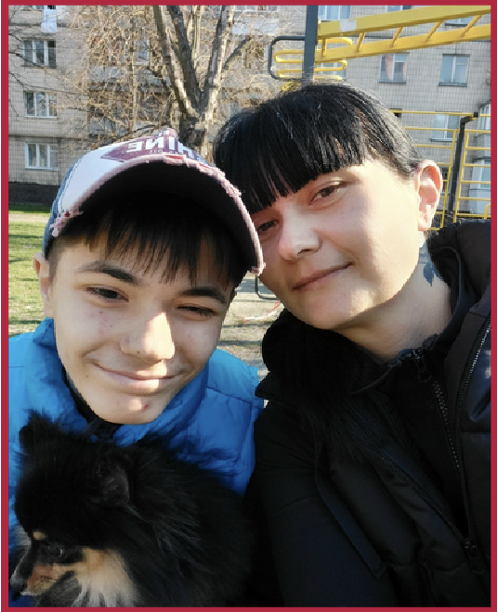

In addition to a structured survey, DRI conducted 24 in-depth interviews and two focus groups with parents. A number of parents also consented to the use of photos and in-depth portraits.

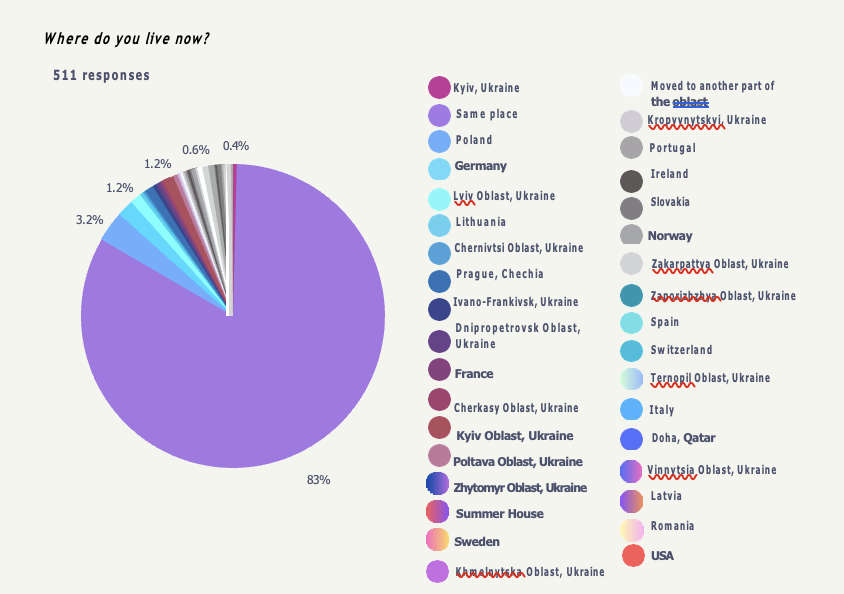

The survey drew respondents from every oblast in Ukraine. Taken ten months into the start of the war, 20% of respondents were internally or externally displaced. This survey, supplemented by interviews and quotes we draw from them, provides a vivid picture of the challenges faced by families that can be used to guide improved governmental policies and urgently needed international assistance.

Despite the recommendations of DRI and our partners in the international community, families report a decline in essential services. While the government provides support to children in institutions at a cost of more than $500/month, the support for children with high support needs living with families is no more than $300/month. The government continues to support institutions at the expense of families – creating incentives to give up children and place them in institutions.

It is impossible to provide everything that is needed with the resources we have available.- Parent, Kyiv

We are prisoners of our situation. Most of the time we spend with our children without a chance even to see a doctor. Social support is minimal. The scariest part is when we are sick ourselves.- Parent, Ternopil Region

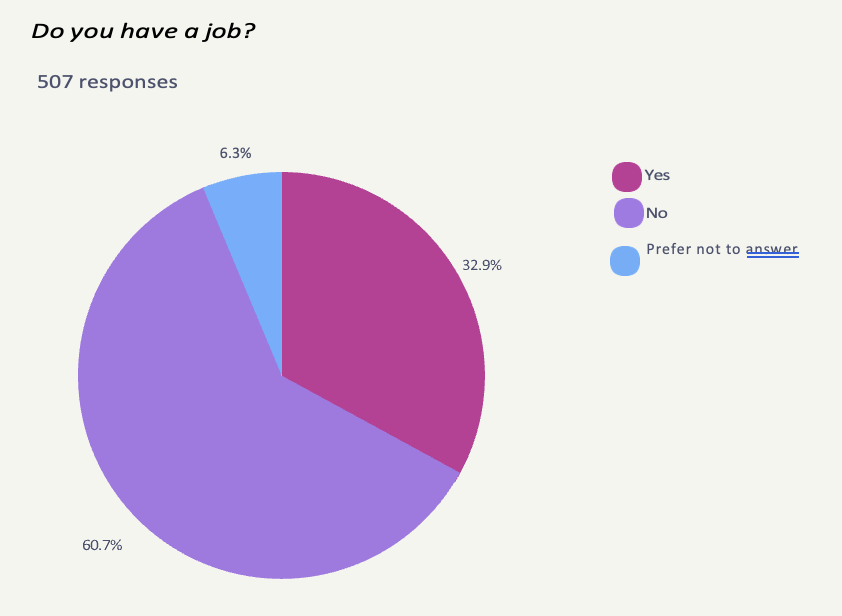

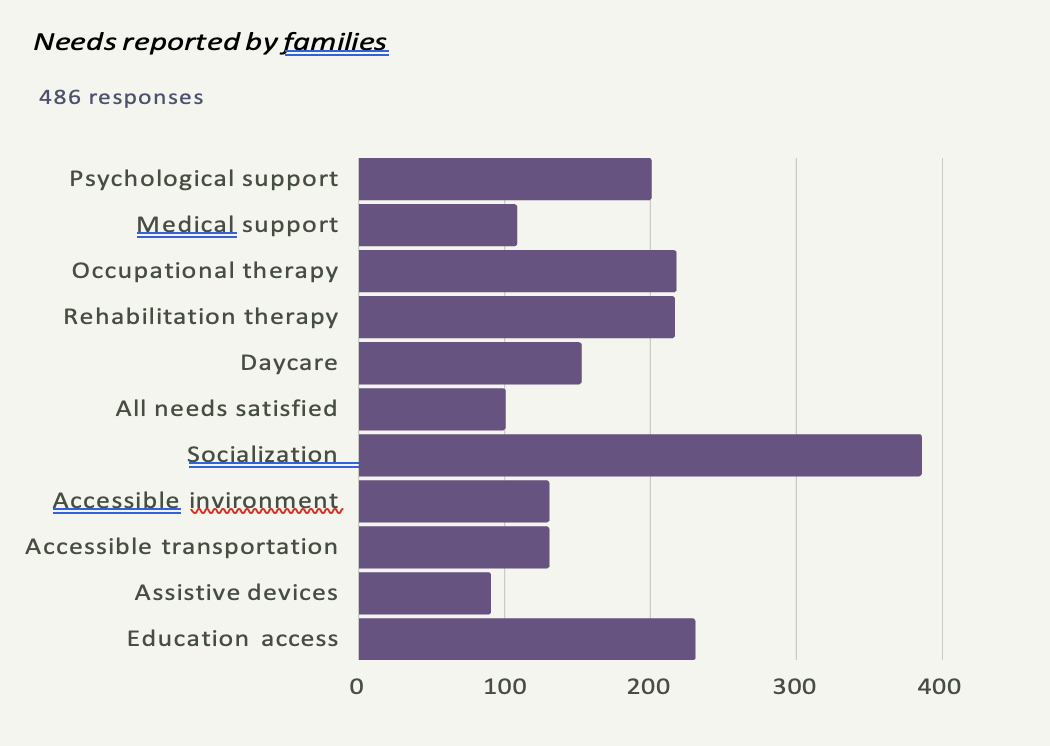

Economic hardship has increased, hitting especially hard for families caring for children with disabilities in the community– despite extensive international funding nearly a year into the war. Overall unemployment has gone up from 224 to 308 of all respondents. Among these families, 79.7% of respondents said that they had access to rehabilitation (or habilitation) services before the war, but only 47.2% had access 10 months after the start of the war. The most frequent unmet needs of children, as reported by parents, are for psychological support (349 of 504) and assistance with socialization of their children (408 of 504). Nearly half reported a lack of access to education (220), rehabilitation, or occupational therapy (216). One quarter reported a lack of access to accessible environments, transportation, assistive devices, daycare, and basic medical support.

With rising inflation, the disability allowance that is provided by the government is insufficient to cover basic needs – creating even more pressure on families to survive or give up their children. The pressures appear greatest for youth and young adults seeking to leave their families and live independently – as families report that there are almost no services to help youth make the transition to independent living.

After he turned 18, nobody cared about what happened to us. - Family, Zhytomyr region

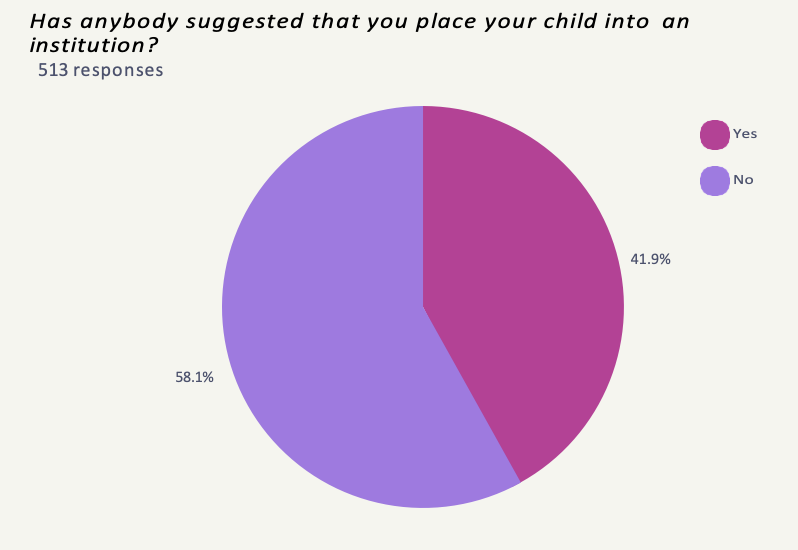

The pressures now placed on families can only be understood based on a picture that was already bleak and extremely difficult before the war. Among survey respondents, 42% of families reported that government authorities or family members suggested that they would be better off if they gave up their children to institutions including doctors (134 of 504 respondents).

To my greatest distress, our local community psychiatrist did everything for us to be forced to go to an institution. We had a really hard time getting out of there.- Parent, Odesa Region

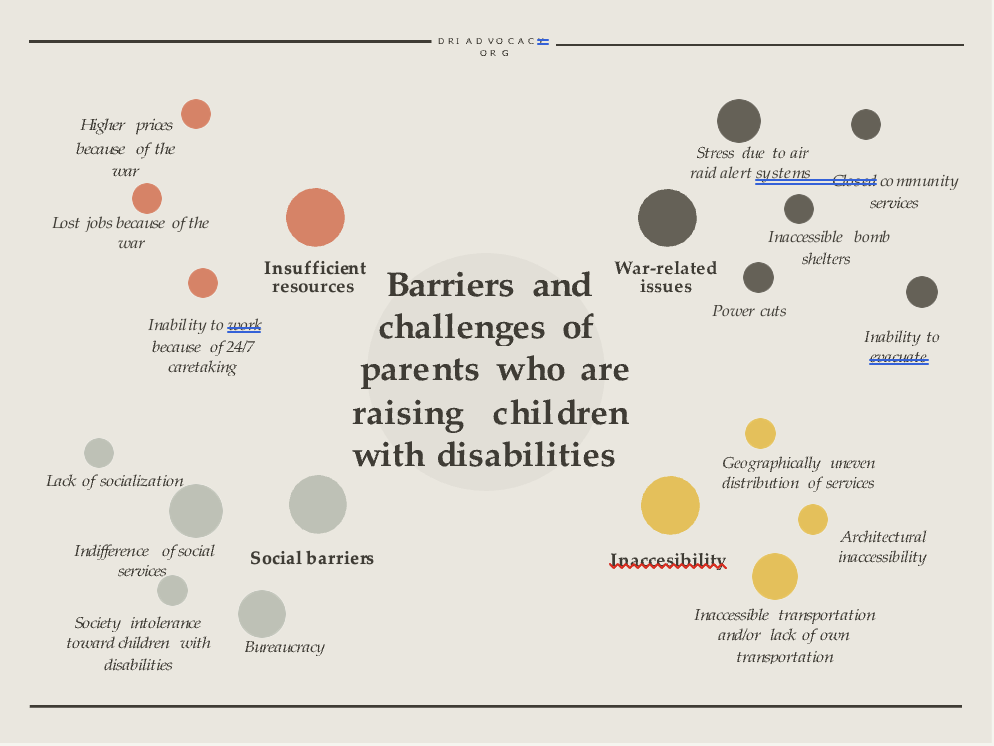

A lack of physical access and transportation limits parents from using services available to others in the community. Bomb shelters are largely inaccessible. In war-torn areas, access to any form of rehabilitation or other support is especially limited. When services are supposed to be available, parents identify a lack of information, a lack of assistance, and tremendous bureaucratic obstacles to obtaining it. Parents also report loss of work because of the war and inability to find new work because of 24/7 responsibilities for caretaking. Without support, families feel tremendous pressure on themselves, which may lead to their own disability.

Trying to save my child, I am ruining myself… All my energy is wasted fighting some stupid barriers in all parts of the social care system.- Parent, Cherkasy region

The DRI survey revealed how the discrimination and marginalization facing children with disabilities is borne largely by women. In the vast majority of cases, 71.8% of respondents reported that they were single mothers raising children with disabilities. Overall, 96.5% of respondents were women. Many of these women themselves are young and report high degrees of economic and social marginalization, discrimination based on the disability of a family member, as well as a high degree of emotional distress under these pressures. They too report the need for personal support and protection. Over the years, DRI has found that young mothers with disabilities are more likely to have their children taken away from them.

Image 2. A stroller with a child with a disability next to the bus

RECOMMENDATIONS

Recommendations – The following recommendations draw from the findings of interviews with families as well as from a meeting DRI convened in July 2022 with the Better Care Network that brought together people with disabilities in Ukraine, family members, service providers, and international humanitarian relief organizations to develop recommendations for immediate action to protect children with disabilities in Ukraine during the war and beyond. These ideas supplement the more detailed recommendations⁵:

- Listen to and include the voices of people with disabilities – and their families. The first-hand experiences of children with disabilities and their families struggling to survive in the

- Careful outreach and support are needed to solicit the views of children with disabilities. This survey has mainly focused on families. To engage the views of children with disabilities themselves, a program of support will be needed to allow them to express themselves and communicate their views in a manner suitable to their own needs and in a context of safety. Efforts should be made at a local and national level to actively engage people with disabilities who are active in disability rights organizations. DRI and DRU’s work on this report provides a general background about the experiences of children with disabilities and their families, and it is not intended as a substitute for the representative outreach to this population, with careful disability and age-appropriate support to ensure full inclusion of the views of children with disabilities that is needed.

- Families will love and care for their children – but immediate support is needed. This should include increased disability allowances that are adequate to meet the basic needs of families of the child with a disability and their family supporters in the household. Additional support is needed so that families have the freedom and support necessary to advocate for the rights and needs of their children.

- Support for independent living and advocacy by youth with disabilities requires support – The survey found a particular gap in support for youth with disabilities. This is a critical age in which young people with disabilities need support to become independent and fully integrated into society, and targeted support can help that transition.

- Women must be recognized and supported – Given the findings that single mothers are the main supporters of children with disabilities in the community, it is essential that mothers must be especially supported to ensure that their voices are heard, they are actively engaged in identifying needs and implementing new policies. Given the economic pressures and history of discrimination against these mothers, donors must provide gender-sensitive support to make this work possible. Support and protections are also needed to help mothers with disabilities keep their children safely in the family.

- Peer support among parents and youth with disabilities can help fill gaps in professional assistance and rehabilitation services – Given the significant gaps in professional assistance and rehabilitation (or habilitation services) available, immediate low-cost supports must be established. Parent-to-parent and disability peer support can help take the immediate pressure off families, allow them to seek employment, and help them fight isolation.

- Support, training, and increased advocacy by and for family members and youth with disabilities are needed to identify the needs of children with disabilities and their families and help government and international donors develop the policies and programs that will be truly inclusive of the views and responsive to the needs of these key stakeholders.

- Families – not smaller institutions or group homes – need support. The CRPD protects the right of children with disabilities to live and grow up with a family. To implement the right to live in the community, as guaranteed in Article 19 of the CRPD, the CRPD Committee has stated that: Large or small group homes are especially dangerous for children, for whom there is no substitute for the need to grow up with a family. ‘Family-like’ institutions are still institutions and are no substitute for care by a family.

- Funding must follow the child -- International support has not yet translated into community support. This finding underscores DRI’s previous recommendations that existing funds from institutions should be shifted to the community through financing established to allow the money to follow the child – rather than being designated for institution-based services.

- New admissions should be stopped, and refugee children should not be returned to institutions in Ukraine. Instead, children should be returned to families or substitute family programs. The immediate needs of children with disabilities in the communities should be met in the context of families to prevent family breakups.

- Human rights monitoring is needed to document conditions in institutions, the needs of children with disabilities and families in the communities, and immediate threats to health and safety they experience.

1. INTRODUCTION

The situation that we have now is not a sprint it`s a marathon. We understand that we cannot get ahead of ourselves, but if we do not do anything - nothing will change. If people who face these challenges on a daily basis do not voice their needs - no one will hear them.- Olena, a family advocacy activist from Ternopil

When a child with disabilities is born into a family it is initially experienced as a stressful event that requires some time for adaptation. However, the lack of support makes this even more challenging.

At first, you face abuse during childbirth, then doctors who caused trauma to a newborn put blame on you, after which they advise you to abandon your child and give birth to a new, healthy one. You decide not to listen to them after all, it is your child. And you must deal with a society that is not ready to accept and tolerate a child with a disability on a daily basis, you experience discrimination, psychological hardship, nervous breakdowns and burnouts, marriage crisis and maybe a divorce, long-term psychotherapy if you can afford it. You also need to constantly seek information, verify all the pseudorehabilitation methodologies by yourself, and finally need to study the neuroplasticity of the brain by yourself to help your child.- Mother of a child born with a disability, Kyiv

That was one of the realities of families before the war. When the war started, she faced another level of challenges. Without her own transportation, she was not able to evacuate her child on time and they spent the first weeks of the war in a local hospital’s shelter in Kharkiv.

I realised that I cannot save my child in situations of emergency or war, and it was a horrible insight.- Mother of child born with a disability, Kharkiv

The family then had to leave the country and seek shelter in Poland where because of the financial hardship they experienced a `loss of dignity`, as the mother reported.

The experiences of families who are raising children and youth with disabilities have been largely overlooked by many different stakeholders and not studied enough to help formulate better state policies and humanitarian agencies' operations. This study aims to shed light on the needs of parents of children with disabilities and give voice to their needs putting it into a larger context of Ukraine`s social care and child protection system as well as ongoing war.

2. DESCRIPTION AND METHODOLOGY

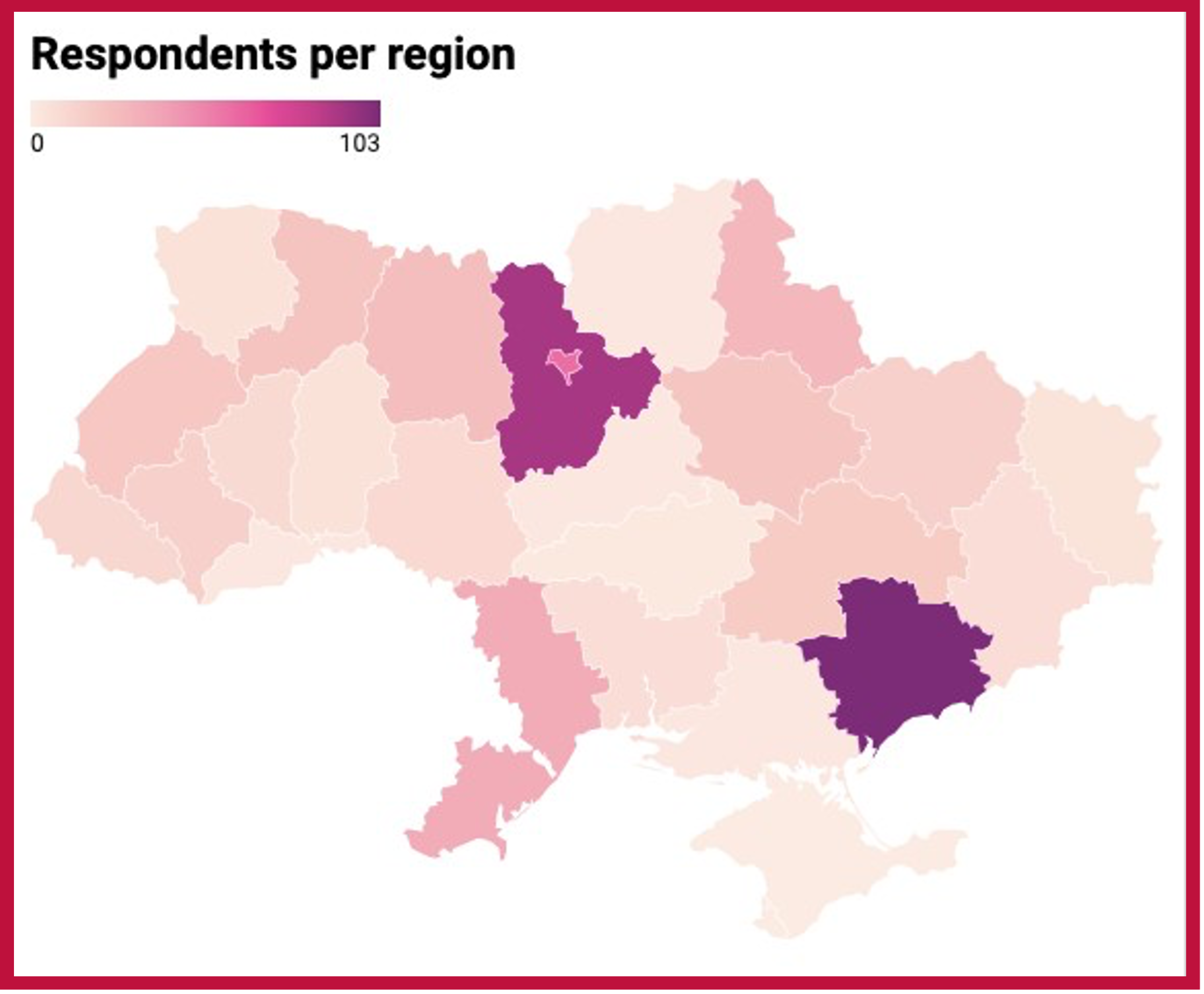

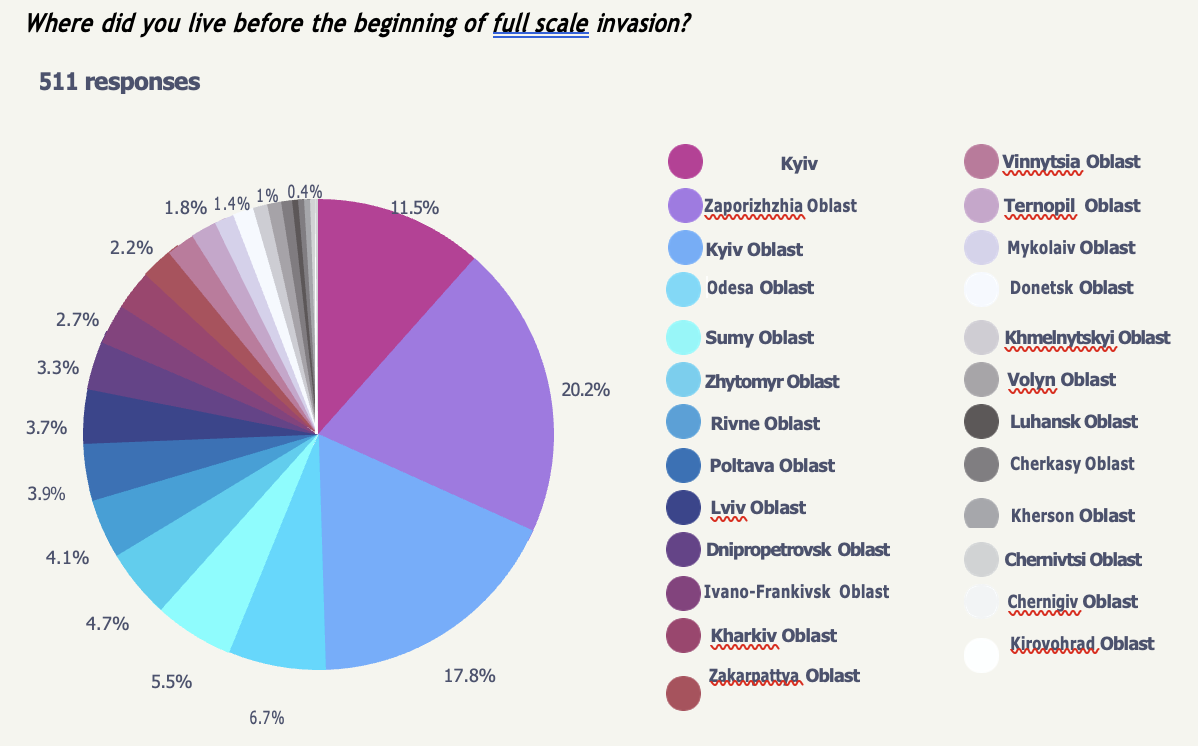

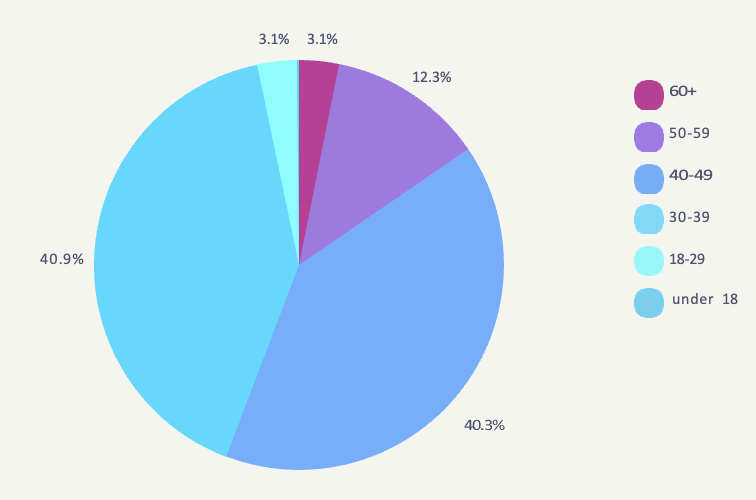

The study was conducted from November 2022 to February 2023 and consisted of a semi-structured self-reported survey, 24 indepth interviews, and 2 mini-focus groups with parents who are raising children with disabilities. The report analyses data obtained from more than 500 respondents from every oblast of Ukraine (except Crimea and areas not controlled by the Ukraine government).

The majority of answers came from parents of Zaporizhzhya oblast (20.2%), Kyiv, and Kyiv oblast (11.5% and 17.8%), and the rest were divided more or less equally between other oblasts. Most of the parents stayed in the same place during the war (81.2%) and the rest were internally displaced or sought shelter abroad.

The majority of the survey respondents were women (96.5%). Most of them - are not married/in a civil union or are divorced (71%) and raising a child/youth with intellectual disabilities and/or autism.

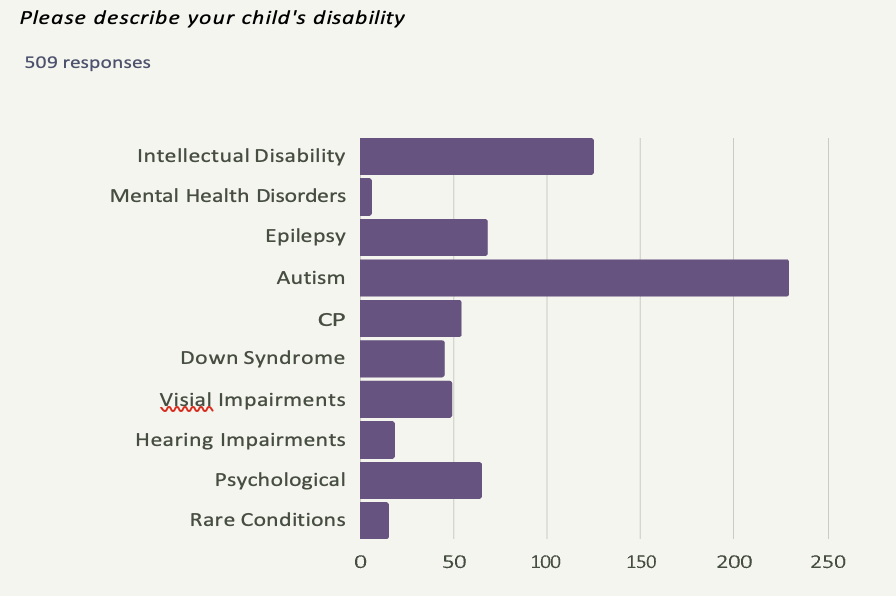

The chart below demonstrates the disabilities of children described by the respondents.

GENDER ASPECT: THE CARE OF CHILDREN WITH DISABILITIES HAS BEEN USUALLY A SOLE RESPONSIBILITY OF WOMEN

After the beginning of the full-scale invasion, the responsibility to care for children, including children with disabilities has fallen almost fully on the shoulders of women. This study represents the voice of mostly solo mothers who are raising children with intellectual and psycho-social disabilities and neurodiversity. According to the study published in 2011 experience of stress raising children with an intellectual disability or autism is similar to findings⁶ on other groups experiencing chronic stress, including parents of children with cancer, combat soldiers, Holocaust survivors, and individuals suffering from PTSD⁷.

In Ukraine, motherhood is usually framed discursively as a sacrifice. Olena Strelnyk, a Ukrainian scholar, published a monograph that explores practices of motherhood in contemporary Ukrainian cities. In `Turbota yak robota`⁸ (`Caregiving as work`) there is a very illustrative narrative of how a mother is expected to give up everything in order to raise her child even if a father is present and a family is full.

Strelnyk has also described how the phenomenon of `working mother guilt` is widespread among Ukrainian women. In her book, Strelnyk does not study the perspectives of those mothers who are raising children with disabilities. Nevertheless, our previous experience of working with parents who are raising children with disabilities confirms that this is true for mothers who are raising children with disabilities even on a larger scale.

CHILDREN WITH DISABILITIES LABELED

According to the Law of Ukraine `On rehabilitation of persons with disabilities`⁹ children with complex disabilities that require constant support 24/7 are assigned a status of disability with sub-group A. These are high support needs children whose parents face multiple challenges due to a lack of rehabilitation and daycare services on the community level for such children. While they are growing up it becomes more challenging to care for them and as a result, they are at most risk of institutionalisation. The same law on rehabilitation lists residential institutions as service providers. A more up-to-date Law of Ukraine on Rehabilitation in Healthcare¹⁰ in addition to rehabilitation also ensures habilitation. In practice, it means a gap for children and adults with complex disabilities since the rehabilitation they are entitled to and the habilitation that they need are split between two different ministries. In most cases, parents of children with disabilities do not have this information.

The system of institutionalisation is set up in a way that children with disabilities up to age 7 can be placed into baby houses (institutions under the Ministry of Healthcare) to receive services and care, at the age of 4-7 children can get to the children’s institution under the Ministry of Social Policy and stay there until they reach 35 (in many cases - until they die) or - if viewed as `educable` by the Medical social pedagogical committee - go to a boarding school according to their disability - an institution under the Ministry of Education.

⁶ As a group, mothers of adolescents and adults with ASD evidenced a profile of HPA hypoactivity as compared with normative patterns manifested by mothers whose similarly-aged children do not have disabilities. This cortisol profile may initially seem counterintuitive given the endocrine response to acute stressors, but it is similar to findings on other groups experiencing chronic stress, including parents of children with cancer, combat soldiers, Holocaust survivors, and individuals suffering from PTSD (Heim et al., 2000; Miller et al., 2002; Yehuda, Boisoneau et al., 1995; Yehuda, Kahana, et al., 1995). Past research on mothers of individuals with ASD has documented their high level of psychological stress (Abbeduto et al., 2004; Seltzer, Krauss, Orsmond, & Vestal, 2000). The present study extends those findings by demonstrating that these mothers also present with the physiological profile characteristic of individuals experiencing chronic stress. The possible adaptive benefits of this down-regulation of hormone activity have been debated, but it may have some undesirable consequences, such as contributing to fatigue and attentional problems. Indeed, a previous study of the present sample suggested elevated levels of daily fatigue in these mothers of adolescents and adults with ASD (Smith et al., 2009).

⁷Maternal Cortisol Levels and Behavior Problems in Adolescents and Adults with ASD

⁸Олена Стрельник. Турбота як робота: материнство у фокусі соціології. Монографія. – Київ: Критика, 2017 [КНУ ім. Т. Шевченка; факультет соціології]. – 280 с., бібл., іл.

⁹ https://zakon.rada.gov.ua/laws/show/2961-15#Text

¹⁰ https://zakon.rada.gov.ua/laws/show/1053-20#Text

¹¹ https://naiu.org.ua/zaprovadzhennya-systemy-rannogo-vtruchannya-mozhe-dopomogty-do-250-000-ukrayinskyh-ditej-z-ryzykom-abo-zatrymkamy-rozvytku/

3. ACCESS TO AND EXPERIENCE OF EARLY INTERVENTION SERVICES

Early intervention is a family-centered system of services that helps children from birth to about 4 years of life, with developmental delays or disabilities, to prevent poor outcomes and realise their full potential. In Ukraine, these existed as private initiatives and in the non- governmental sector since the 2000s in a few areas of the country (Kharkiv and Lviv as pioneers).

The majority of answers came from parents of Zaporizhzhya oblast (20.2%), Kyiv, and Kyiv oblast (11.5% and 17.8%), and the rest were divided more or less equally between other oblasts. Most of the parents stayed in the same place during the war (81.2%) and the rest were internally displaced or sought shelter abroad.

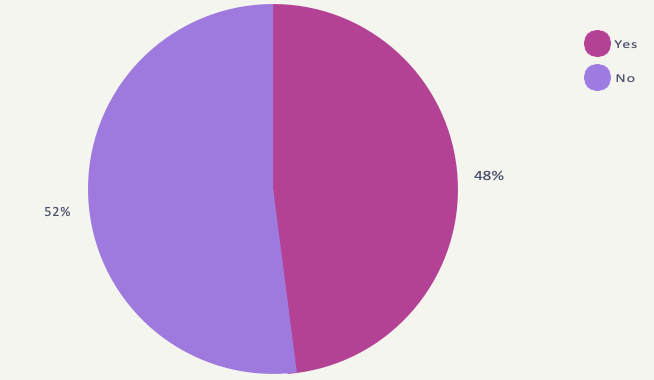

This means that many children born before 2017 had no access to early intervention services: 52% of the respondents did not receive these services.

I did not hear about early intervention in 1986 - Parent, Dnipropetrovsk region

Early intervention started too late for us and did not have a strong effect - Parent, Kharkiv region

Early intervention services became available in our city when my child grew up already - Parent, Odesa region

Good specialists are mostly located in Kyiv and mostly in the private sector. It took us a lot of time and resources to receive them. - Parent, Kyiv region

The numbers might be higher as the survey demonstrated a lack of understanding of what early intervention stands for. Some parents mentioned social allowance, free shoes or a stroller, intensive care, dental assistance, diapers, assistive devices provision, surgical intervention, etc. Some of the respondents said they did not understand the question.

Those who did have access to the services describe their experience as positive. Nevertheless, parents said almost three- quarters of services were private and paid out of pocket. In some cases, parents could not find adequate specialists in the area and had to become specialists themselves.

It is during the early intervention program that we started working with a psychologist, speech therapist, and occupational therapy. It was a very positive experience. - Parent, Zakarpattia region

Early intervention helped me a lot as a mother to understand my child and to better interact with him, to help him develop his potential and to start his socialisation. - Parent, Kharkiv region

We regularly had early intervention and it brought positive results. Everything depended on the specialists and frequency of attendance - Parent, Zaporizhya region

I decided to receive additional education in neurodevelopment and psychology to become a specialist for my child, and children like that - Parent, Kyiv

Image 5. Child sits at the table holding a toy

4. ACCESS TO KINDERGARTEN (EARLY SOCIALIZATION)

In Ukraine, state-run kindergartens are free and accept children from the age of 2 until 7. Private kindergartens admit children as early as 18 months. During wartime, kindergartens are required to have bomb shelters to operate, and the number of children that can be in one group is now limited to 12 (compared to about 25-30 before the war). In some regions of Ukraine, children can be in kindergarten only if both parents are employed, and in some cases - only if they are employees of critical infrastructure (medical facilities, transport, military, etc.)

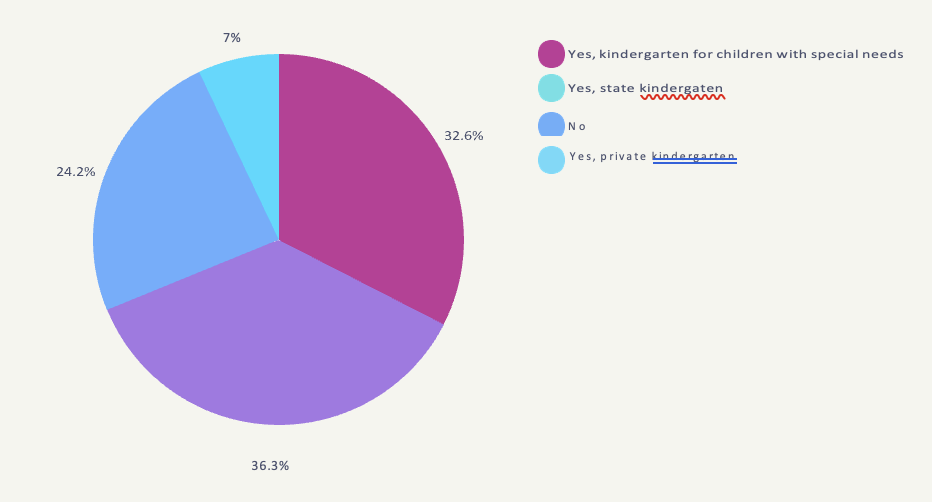

Nevertheless, children with disabilities had limited access to kindergarten long before the war: 24.2% of the respondents said they had no access to kindergarten, and 7% said they could only go to a private one. Inclusive education reform in Ukraine describes an inclusive kindergarten group¹² as a group with no more than 3 children with disabilities at a time (in total - no more than 15 children). Inclusive groups can be created at the initiative of kindergarten staff and the identified levels of support are 1…5. An inclusive group needs to have 1 assistant teacher per group (financed from the local budget) to ensure an individual approach to each child with disabilities in the group. A child can also have a personal assistant (the cost is covered by parents). Those who could not attend the kindergarten were mostly denied access due to disability and/or the absence of inclusive groups in the kindergarten close to them.

We were denied access because of my child’s disability - he was wearing a diaper and they did not accept children of his age who are using diapers. – Parent, Chernihiv region

The closest kindergarten to us was not ready to admit my child. So, he had to spend most of his time at home except for the periods when he was receiving rehabilitation services – Parent, Ternopil region

A state-run kindergarten did not want to take us because of the disability, and there was no special needs kindergarten in our areas – Parent, Zaporizhya region

There are no specialised groups for children with autism in our kindergartens – Parent, Zaporizhya region

My child has high support needs and cannot take care of himself, so we were told to stay home – Parent, Zaporizhya region

They did not want a child with a disability in a group with a lot of children, and there was no inclusion in that kindergarten – Parent, Odesa region

My child was not accepted to a kindergarten because they did not have specialists working with children with autism. – Parent, Zaporizhya region

My child did not speak until he was seven and we were not accepted into a kindergarten. – Parent, Zaporizhya region

There are no kindergartens that accept children with both physical and intellectual disabilities. – Parent, Kyiv region

My child was denied access to kindergarten because he has epilepsy. – Parent, Ternopil region

We could not get into a regular kindergarten, and there was no specialised kindergarten close to us. – Parent, Zaporizhya region

Children with autism are not admitted to kindergarten. – Parent, Zaporizhya region

Even in inclusive groups in the kindergartens, some children were denied participation because of high care needs and low motivation of the staff.

They did not want to have my child (because of his disability) even in inclusive groups. – Parent, Zaporizhya region

The attitude was not professional. – Parent, Sumy region

Teachers don’t care, they are just checking the box and are not interested in the needs of a child. – Parent, Kyiv region

A lot of barriers were created by the staff of the kindergarten. They did not want my child there and did everything for me to take her out. – Parent, Zaporizhya region

The teachers had no experience or motivation to work with children with intellectual disabilities. – Parent, Cherkasy region

Parents also noted the low qualifications of the specialists working with children in kindergartens. The biggest barriers occurred for children with autism and those who were non-verbal or partially verbal, as well as those with intellectual disabilities. Teachers have low qualifications and lack training and experience on how to address the educational needs of children with disabilities. Hence many respondents described the negative experience of kindergarten for their children. They said their children were ignored, left alone, and not engaged in any activities. Their needs were not understood, and they faced bad attitudes toward them and attempts to expel them from kindergarten, some children were continuously transferred from one kindergarten to another.

My son cannot walk, and the teachers had a really poor attitude toward him because of that. - Parent, Zytomyr region

Because of the behavioral issues, the teachers hinted that we should stay home instead of helping him with adaptation and socialization. Nobody had any desire to work with a troublesome kid. - Parent, Luhansk region

They scared my child with something in the garden so much that we now cannot even walk in that neighborhood - my child starts crying when he sees a familiar route. - Parent, Kyiv

My son was in a small group of children with developmental delays. They did not know what to do with him because they had no previous experience. They did not include him in group work and he always had to sit separately. It was sad. With time they asked me not to bring anything for creativity classes because he is not using it, he doesn’t know how to draw and does not want to do it. Even though I know he likes it. I realized that my son is spending 4-5 hours a day in a kindergarten doing nothing and so I took him back home. My parents helped me with caregiving so that I could continue working. - Parent, Zaporizhya region

My child cannot walk or sit herself, so they did not bring her outdoors like other children. - Parent, Sumy region

Other challenges included a lack of accessible transportation if a kindergarten was far from a place of residence, the absence of a special diet in an otherwise centrally planned menu for all children as well as resistance from parents of children without disabilities. The absence of required vaccination (for medical reasons) was often a barrier to being admitted to a kindergarten. Children with high support needs required a personal assistant to continue attending kindergarten and not all parents could afford it.

The administration did not understand why my child needs a special diet. - Parent, Sumy region

We attended an inclusive group. Parents of children without disabilities were against it and said that my son interfered with the educational process. - Parent, Kyiv

However, there were also positive experiences of kindergarten for some children. Mostly positive experiences correlated with either private kindergartens with fewer children and individual approach or NGO-run daycare centers. Parents noted that being included in different activities together with children without disabilities promoted the development of their children and made them ready for school. Another big advantage of being in a kindergarten with supportive staff is that children become more independent and able to take care of themselves compared to those who stayed at home.

The survey showed a correlation between those who received early intervention services and those who later were able to attend kindergarten. Roughly 70% of those who had access to early intervention were able to get into specialized kindergartens.

5. ACCESS TO REHABILITATION SERVICES

Rehabilitation is a set of interventions designed to optimise functioning and reduce disability in individuals with health conditions in interaction with their environment.¹³ Children and adults with disabilities require a systemic and comprehensive approach to rehabilitation to be integrated into everyday life and uncover their full potential.

Rehabilitation services are available in state-run rehabilitation centers (the state covers a course of rehabilitation once a year per child¹⁴) and in private facilities. In some regions, there are NGO-run services that could be free or partially compensated.

Every month of the war brings in more people who received disabilities as the result of hostilities and who require rehabilitation hence diminishing access to the services for children and youth with disabilities.

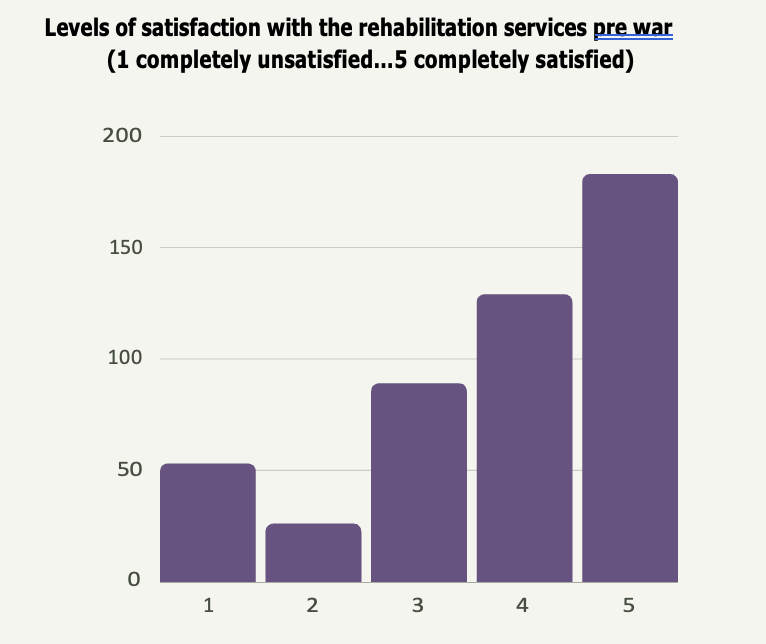

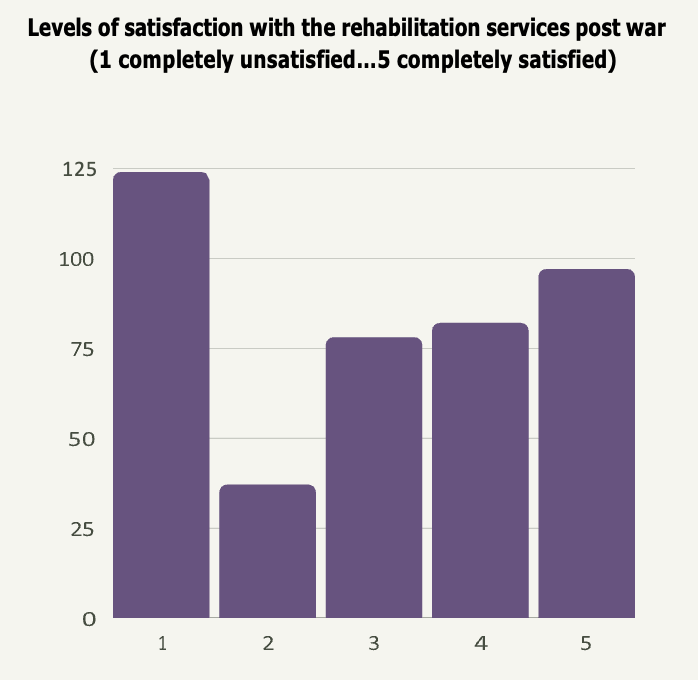

79.7% of respondents said they had access to rehabilitation services pre-war. Only 47.2% have access to rehabilitation services after 10 months of the war. Satisfaction with the provided services has also changed after the start of the war.

According to the respondents, there is a lack of affordable community-based services. Most services are quite expensive and taking into account considering that parents of children with disabilities are often unable to be employed because of 24/7 caretaking for their children with disabilities. The disability allowance is not sufficient and often can barely cover basic needs such as food, clothes, and medicine. At a time of war, the prices for everything have gone up and a lot of specialists left.

We have difficulties finding specialists to teach a child the basic things. -Parent, Dnipro region

There are private centers where we can get services, they are open. However, because of the war and its effect on our budget, we can no longer afford it. - Parent, Kyiv

We used to go to state-run and private rehabilitation centres. After February 24, 2022, the ability to do it declined; the local state-run centre was closed for a while; the alternative one hosted IDPs, and we can no longer afford private rehabilitation services. - Parent, Kyiv region

Some rehabilitation centres are open. However, the cost of the sessions has increased while the income has gone down since the beginning of the war. Hence, we have access to services, but often we cannot afford them. - Parent, Kyiv

Due to the war and power cuts my child cannot get to the rehabilitation center every day and her development is slowed down because of that. - Parent, Odesa region

Another problem with services is their uneven geographic distribution and inaccessible environment. Those who live in rural areas or in smaller cities do not have any services close to them and/or accessible transportation to travel to get to the closest ones.

We could really benefit from `social` taxi - it would increase accessibility of services for my son. - Parent, Kyiv region

It is difficult to plan rehabilitation services because of constant shelling, power cuts, and lack of transportation. - Parent, Sumy region

Very difficult resource-wise. Food, medicine that my children need all the time, prices for private sessions with specialists. And it is very difficult to have no transportation when you are raising two children with autism. - Parent, Ivano-Frankivsk region

Another barrier to receiving services is bureaucracy. Usually, parents need to collect a whole list of documents and certificates to be eligible for state-paid services. In many cases, parents reported a lack of accessible information to even figure out what these documents are. The social services responsible for providing this information are reported to be of little help and not family-friendly in their approach.

The state paid for services of a psychologist, physical rehabilitation specialist and defectologist in a rehabilitation center. However, in order to receive these services every three months we had to go through a screening committee and collect a lot of documents and certificates to become eligible. Sessions lasted 30 min each twice a week. When my child turned five I realized that he is not ready for school - no one is trying to teach him numbers or letters, and there is no systemic approach. The rehabilitation center told me they do not offer such services. - Parent, Odesa region

Rehabilitation procedures are usually offered by the government in spring and fall - seasons when my child with high support needs is extremely prone to respiratory diseases. I wish there were mobile teams from these state-paid services because otherwise we end up missing out on the free services and later cannot afford private ones. Some categories of children require special food categories to ensure their nutrition and often those are more expensive and/or not available. It is very important for social services to be on top of these needs to be able to offer support. - Parent, Ternopil

Youth with disabilities are completely underserved. There are almost no rehabilitation services for youth and adults with disabilities. As soon as a child with a disability turns 18 - they are falling through the cracks in the system.

After he turned 18 - nobody cares about what happened to us. - Parent, Zhytomyr region

Rehabilitation centres that serve children with disabilities cannot accept youth or adults with disabilities. Since the opportunities for employment and other meaningful activities are very limited - youth and adults with disabilities in the community are left completely under the responsibility of parents or caretakers. There is no service of personal assistance and very few examples of supported living for adults with disabilities. All the above leads to increased risk of institutionalisation.

¹³ https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/rehabilitation

¹⁴ https://zakon.rada.gov.ua/laws/show/309-2019-%D0%BF#Text

Image 6. Four children with disabilities in wheelchairs celebrating a birthday

6. INSTITUTIONS – NOT SAFE PLACES FOR CHILDREN

The general public who has had no experience with disabilities, or relatives with disabilities, perceive institutions as the only appropriate way of caring for children and youth with complex disabilities. A typical stereotype sounds like this:

What else do they need? In time of war they have a roof above their heads, food, clothes, and doctors around 24/7

In fact, even that is not fully true. Institutions under the Ministry of Social Policy and the Ministry of Education are not healthcare institutions and cannot provide adequate specialised medical care and in case of medical needs children are brought to the community hospitals or emergency rooms.

The cost of running an institution is quite high, nevertheless. For example, a Ministry of Social Policy institution in the Vinnytsia region that has 116 children and youth with complex disabilities according to their budget in 2021 received about 700 000 USD. The amount received from charity organisations in the form of in-kind donations is not known. That means that the care of a person in this particular institution costs the state about 500 USD per month. If this money followed a child (a family) or was invested into community services - it could lower the rate of institutionalisation.

To compare - families who are raising children with high support needs (like those in the Vinnytsia region institution) receive about 300 USD.

Institutions are a horror. Why do parents institutionalize their children? Because they are told that their children are incapable and will not develop mentally. - Parent, Kharkiv region

When asked if they had heard suggestions of institutionalizing their child almost 42% of the parents said yes. The most common responses on who suggested to do the placements were:

- doctors (134 families)

- strangers (95 families)

- family members (51)

- and friends (35)

Parents also reported cases when teachers, state-run community service providers, and social services authorities recommended institutionalization as an option.

To my greatest pity, our local community psychiatrist did everything for us to be forced to go into an institution. We had a really hard time getting out of there. - Parent, Poltava region

This is our only long-awaited child. We do not want to give her away. - Parent, Kharkiv region

I have to confess that I was thinking of placing my child into an institution myself when we have difficult periods with him. - Parent, Mykolaiv region

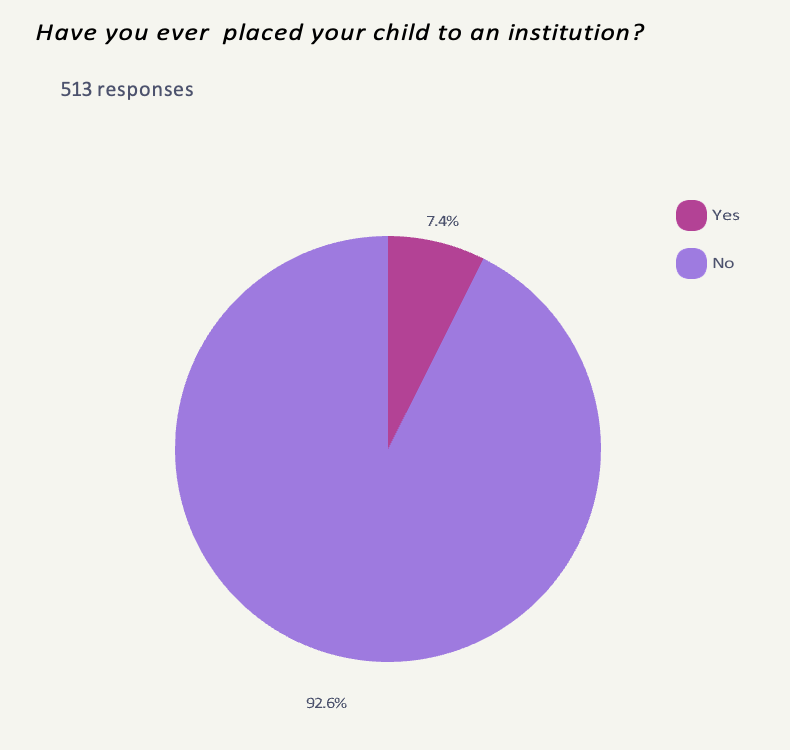

Out of all the respondents, only 7.4% did end up placing their children into institutions. 42 families had their children in boarding schools, 6 - in the adult facilities, and 3 - in the ministry of social policy children's facilities.

Adult social care facilities are among the biggest fears of parents who are raising teens and youth with disabilities. At this stage, they realize that when they are gone the most likely option for their children is a so-called psycho-neurological internat - an adult facility under the Ministry of Social Policy (or - in some cases - Ministry of Healthcare).

Imagine the situation when a mother is raising a child with a disability on her own and there are no relatives willing to take care of the child. What happens if that mother gets sick, gets into an accident, or needs hospitalization? - an institution is usually the only option for her child then. - Parent, Ternopil region

Parents who have their children in institutions are afraid to speak out about what is happening there because of fear that the institutions will be closed, and they would be left alone with their children. It means that they are not going to be able to work or pretty much do anything. - Kharkiv region

My son could add large numbers when he was 3 years old, he could solve simple math problems. However, there was nothing for him in Kharkiv or Kharkiv region and he had to go to a specialised boarding school for children with developmental delays. His math talent was completely destroyed there. - Parent, Kharkiv region

7. NEEDS OF FAMILIES (BOTH PARENTS AND CHILDREN); BARRIERS AND

CHALLENGES

When answering this question, a significant number of parents did not acknowledge their own needs and instead answered about the needs of their children. Usually, the caretaking for children and the elderly in the family falls onto women. In the case of raising children with disabilities, their mother is expected to fully dedicate her time and effort to caretaking foregoing her personal and professional development. One of the mothers from the Cherkasy region vividly described the way she felt after her child with disabilities was born:

There is an abrupt loss of social status: after a child with disabilities was born my role has been reduced to that of a caregiver in society, and my needs seem to be limited by this role. Psychologically I have burnt out and this fatigue interferes with the decision-making process and diminishes my ability to advocate for my child. I always need to fight for getting everything we are entitled to - education for instance. My child is non-verbal, and she started reading at the age of 4, but nobody cares that severe physical disability does not always go together with intellectual disability. Our family cannot afford special equipment such as an eye-tracker and other assistive devices that could help my child be more included in society. - Parent, Cherkasy region

Among the most pressing needs of parents are temporal and financial resources that tie into each other. Due to the lack of daycare and accessible education options that would include children with disabilities at least one parent has to stay home and take care of the children.

Hence, they are not able to have a full-time job and are dependent on disability allowance for a child¹⁵ (the amount in 2023 varies between 1255 and 2093 UAH which are 34 and 56 USD respectively depending on the category of needs defined by governmental bodies; there are also additional payments to parents who are unemployed and dedicate their time to childcare¹⁶).

It is impossible to provide everything that is needed with the resources we have available. Rehabilitation, physiotherapy, rest and recuperation, lack of specialists, lack of access to information, and inability to work because I don`t know whom to leave a child with. - Parent, Kyiv

We are prisoners of our situation. Most of our time we spend with our children without a chance even to see the doctor. Social support is minimal. The scariest part is when we are sick ourselves. There are no effective mechanisms for monitoring crisis situations in at-risk families and we are left with our problems alone. - Ternopil region

There is a big need for part-time and distant employment options for parents of children with disabilities. - Kyiv region

I am alone with my daughter 24/7, my husband is in the military. My hands are tied because I do not have where or with whom to leave our daughter - Parent, Zhytomyr region

The majority of survey respondents are people aged 25 to 54 (which means that they should be considered in the labour force¹⁷ and in their prime economic activity¹⁸). Before the war 44% of the respondents were unemployed. After the 10 months of the war - the unemployment rate was more than 60%.

Lack of employment and accessible leisure for children with disabilities combined with 24/7 caretaking results in the social isolation of families. Most parents reported socialization as one of their top needs. This takes a toll on their physical and mental health and well-being. This leads to another most reported need of parents: that of psychosocial and medical support.

I think now that if the rights of my child were fulfilled, I would not have to substitute the whole staff of specialists. I would be able to just take my child to the kindergarten or school where she would have opportunities for socialization and development, where she would be taken care of by people who have more experience and skills in this - then I would be able to solve the majority of other problems myself. Now, however, trying to save my child I am ruining myself. And I am not even sure if I am properly helping my child. All my energy is wasted fighting some stupid barriers in all parts of the social care system. - Parent, Cherkasy region

I need psychological help with my depression. Because of constant distress, I now have chronic diseases and need medical support as well. - Parent, Dnipro region

I feel a huge deficit of personal space and time for myself. - Parent, Lviv region

No one thinks how difficult it is health-wise to take care of a growing child with high support needs. He is getting heavier and heavier, and we live on the 4th floor of an apartment building with no elevator or ramps. - Parent, Ternopil region

One of the aspects of isolation is insufficient access to information. The survey respondents stated a need for information about the disability of their child and how to best care for them, about services and benefits they are entitled to as well as how to go through bureaucratic challenges at all stages of life.

When a child with a disability is born, we do not know as parents what to do with this. We need some training and ongoing informational support. It would be also good to get timely information on what services are available for our children in the community. - Parent, Kyiv region

Social services workers seem completely uninterested in providing information to families who are raising children with disabilities - I always need to go there and beg for information. - Parent, Poltava region

My son received a summons to the military office even though he has an intellectual disability. We now must go through the whole process to get him cleared. It is very unnerving. - Parent, Kryvyi Rih

The most frequently mentioned needs by parents who are raising children with disabilities both for themselves and for their children are socialization and need for psychological support. Mothers of children with disabilities report high levels of isolation and emotional burnout.

¹⁵ https://zakon.rada.gov.ua/laws/show/2109-14#Text

¹⁶ https://dszn.smr.gov.ua/derzhavna-sotsialna-dopomoga-invalidam-z-ditinstva/

¹⁷ https://ukrstat.gov.ua/druk/publicat/kat_e/2020/08/Zb_rs_e_2019.pdf

¹⁸ https://data.oecd.org/emp/employment-rate-by-age-group.htm

BARRIERS AND CHALLENGES

-

Bureaucracy

We started seeing an incredible thing: teenagers with developmental disorders are summoned to the military. On the border - if you do not have a `white ticket` (*a waiver from military service) the border guards cannot and will not let you out. - Parent, Kyiv

-

Geographically uneven distribution of services

Because of the war, we cannot attend habilitation sessions, he is now more than ever scared of loud noise, sirens, and dentists (hence - the teeth are really bad). We live in the village and now that the public transportation (buses) was cut down - we cannot even get anywhere.- Parent, Zhytomyr region

-

Inaccessible transportation and/or lack of own transportation

During the war, a lot of trolleybuses and trams have limited ability to function, and only private transport companies remain consistently active in the city. Their minibusses have such narrow doors that I cannot fit a stroller with my kid who has a complex disability including limited mobility into the bus. The taxis are not affordable for us. - Parent, Odesa region

-

Architectural inaccessibility (including inaccessible bomb shelters)

Inaccessibility: there is no way to get into the bomb shelter with a wheelchair or a stroller, on most public transportation stops we cannot get into the bus or into the train.- Parent, Cherkasy region

-

Indifference of social services

Social services are like an ulcer on the body of parents of children with disabilities. Even in a big city like Lviv I need to take care of all the problems of my child with disabilities and seek services. I had no idea that Directives 309 and 31 even exist (Directives of the Cabinet of Ministers that allow state compensation for rehabilitation services). - Parent, Lviv

-

Society intolerance

Insufficient resources:

Insufficient resources:

- Inability to work because of 24/7 caretaking

- Higher prices because of the war

- Lost jobs because of the war

With the war I lost all the income I had; I am no longer employed. The child is constantly with me since I am a single mother. - Parent, Zaporizhya region

We cannot afford the timely medical exams and laboratory tests necessary to provide timely treatment to the child. Because of the war, my husband lost his job and I only work part-time. - Parent, Sumy region

-

War Impact

- Closed community services

We used to attend sessions with different specialists. Everything has changed since the beginning of the war. My child lacks quality work with professionals and it has taken its toll on her development. - Parent, Lviv region

-

Stress due to air raid alert systems

With the beginning of the war, children became more anxious. Because of combat operations in our region, a lot of qualified specialists moved out to safer regions or joined the military and children do not have access to quality medical services. Because of frequent air raid alerts we often need to cancel the appointments in those rare cases when we were able to find a specialist. The same reasons prevent our children from getting daily rehabilitation services. - Parent, Zaporizhya region

The city is constantly under shelling, and it prevents us from going to the rehabilitation centres. - Parent, Zaporizhya region

Our life consists of attempts to get to the rehabilitation session in between air raid alerts. - Parent, Kyiv

-

Frequent power outages

There is no electricity, and we cannot attend rehabilitation sessions. A lot depends on themother and how much she can invest into child’s development. In our case we have had good prospects. It’s a pity we are losing our time because of power cuts. - Parent, Odesa region

Nothing has changed with the support during the war. The whole system had shut down during the pandemic and is like this during the war. Now we do not have access to the Internet and my child cannot study. It has taken a toll on his development and now we need to start all over again. - Parent, Dnipro region

-

Inability to evacuate

I do not know about any needs analysis done by the government so far. When we are talking about children with disability of subgroup A (*high support needs children in Ukrainian law) who are completely dependent on blenders, inhalation's, disinfection devices - there is an acute need for those, and they need to be battery- powered because of frequent power cuts. We do not know how many of these kids did not evacuate abroad and stay behind. What if they need medication that is no longer imported? - Parent, Ternopil

APPENDIX A SELECTED

FAMILY PROFILES

Valentyna and Vova

Valentyna together with her husband and a 12-year-old son Vova is one of the families that decided to stay home despite the danger posed by the russian aggression. They live in Odesa. Her husband has been unemployed since the start of the war, and Valentyna has mostly stayed home taking care of Vova.

Vova has CP from birth. The specialists told her early on that he is going to be non- verbal and will never learn how to read or write even though his intellect is intact. Imagine their surprise when one-day Valentyna discovered that Vova can communicate by pointing to the letters of the alphabet.

I accidentally showed him the ABC and he started pointing to certain letters making words. Apparently, he could understand us, but did not have a way to communicate it.

This incident set the beginning of a fascinating process of discovering their son`s likes and dislikes, the whole inner world. Vova is using a wheelchair to move around and does not attend school because he was deemed `uneducable` until recently.

Now Vova has a friend with whom to chat online. His mother is helping him with that until they are looking for a device that would help the boy do it independently.

Vova acts as a typical teenager, and he wants to have his own private space. I do not want him to depend on us forever

Their apartment building is not accessible, there is no elevator, so they do not get outside as much as they would want to. However, this is all easy to cope with in comparison to the constant threat of russian invasion.

Natalia and Veronika

Veronika was born without a disability. After she turned 1, seizures started. Natalia, her mother, consulted many doctors, but nobody could figure out what was wrong. Anti-seizure medications they prescribed for Veronica stunted her development and motor skills, yet did not help with seizures.

After four years, the family ran out of money (only Natalia`s husband could work, she had to take care of the child) and they decided to experiment with getting off the medication. With the professional help of a doctor, they started decreasing the dosage until Veronika could fully stop taking the medication. Natalia noticed that it helped her child recover her mobility. Veronika, who is now 15, has an intellectual disability and epilepsy in 9-year remission. She is non-verbal but can communicate her needs clearly. She loves music and glossy magazines. The girl can walk, and swim and she loves to exercise.

This is all thanks to her mother who refused to accept that her child would be bedridden. To teach her to walk Natalia had to take Veronika to a sidewalk next to a very loud avenue so that her screaming would not attract too much-unwanted attention.

Our people are still overreacting to children whose appearance or behavior is out of the normal range they are used to. I hated unwelcome attention and advice.

The war did add stress to their lives, yet Natalia remains optimistic. Her husband lost his job and their neighborhood in Kyiv was regularly under shelling. They slept fully clothed and sometimes in the bathroom for safety purposes. To make it a little better for Veronika, Natalia bought her daughter headphones, so she could listen to the music during shelling to mitigate the stress. They decided not to leave their home in Kyiv. Natalia knows that it would cause a lot of problems for Veronika's development.

I struggled so much to ensure her epilepsy is in remission that I would not risk getting it back.

Besides, Veronika is very attached to her father, and she will not be happy without him in a new environment. Natalia and her husband are confident that they can cope with anything that lies ahead.

Kateryna and Mykyta

Kateryna and Anton are both 36 and they have two children - Mykyta, 7, and Eva 1.5. Mykyta has CP and epilepsy from birth. The family lives in Dnipro and is also taking care of two senior grandmothers. Before the war, only Anton had a job, because Kateryna was on maternity leave. The family budget was already stretched thin - they had to provide for their elderly parents as well as the kids. On February 24 the time stopped, and days turned into endless survival without plans and in constant tension. Mykyta`s children's teeth did not fall out and at his age, it meant he had to have them surgically removed. Because of the war, it was neither possible nor did they have money to do it. They also had to discontinue all the rehabilitation activities for Mykyta. Volunteers helped with anti-seizure medication and diapers; in March they did not have money to buy milk, eggs, and vegetables, not to mention meat.

It would be very difficult for us to survive without humanitarian aid and cash assistance.

They spent several months on some crumbs until humanitarian aid reached them. Kateryna and Anton really worried about their kids and elderly mothers - it was a tough time for them. Now the situation is more stable, but her husband is still out of a job.

I often cried from hopelessness. We could not do anything for those who depended on us.

Kateryna decided not to leave Dnipro for a safer place because it would cause deterioration of state for Mykyta. Also, she did not want to be on her own with two young kids without the support of Anton. Mykyta loves his younger sister very much; even though he is bedridden, and she is hyperactive - they find ways to play together.

Eugenia and Demid

Eugenia and Demid live in Novi Petrivtsi - a small town right outside of Kyiv which was one kilometer from the russian offensive in February. Demid is 11 and has autism. His mother is raising him alone. Demid is a very smart and caring boy; he attends a regular school in their neighbourhood.

When the war started, they stayed home for the first three weeks, and it was very scary. A lot of their neighbors together with their children left, the only ones who stayed were the elderly and people with disabilities. Eugenia was afraid to evacuate: russians killed a lot of civilians who tried to leave the besieged towns around Kyiv. She and a few neighbours that stayed behind felt it was their duty to take care of the abandoned pet animals and senior people.

The Red Cross refused to go to that town to bring humanitarian aid because it was dangerous in February and March. It was impossible to get any help or cash assistance for the first weeks. Demid is on a gluten-free and lactose-free diet and when they finally got some food, they could not use it and decided to distribute it among those in need.

Cash assistance was only available for those families who had more than one child, regardless of disability.

Once we got together with our neighbors and went to the office Red Cross in Kyiv - they refused to give out the aid to us because we lived outside of Kyiv at the moment.

With their town being relatively safe these days, Eugenia wants to stay home and avoid the hardship of being internally displaced. Because of his neurodiversity, Demid is very dependent on clear planning, he needs certainty. Leaving the familiar environment would cause tremendous distress.

In her twenties, Eugenia worked for three years in a supported living hostel for people with intellectual disabilities in Israel. Then her son was born, and she realized that even though there are some services for children with autism, adults are in a less advantageous position.

I do not know where Demid will go when he turns 18. We don`t have any socialization opportunities like that in Ukraine.

Liudmyla and Anna

Liudmyla, her husband, and two children live in the Dnipro region. Anna, the younger daughter, has CP as a result of the doctor's mistake in labor. The lower part of her body was affected, and she cannot walk. However, there is no intellectual disability.

Anna attends a regular school. It was only possible because her mother Liudmyla quit her job as a municipal clerk and became her daughter`s personal assistant in school. According to inclusive education reform, Anna was not eligible for a state-funded personal assistant because her intellect is intact. Still, the girl would not be able to attend school by herself because she is in a wheelchair, has mobility problems and the school premises are not accessible.

Liudmyla is acting as her daughter`s advocate: she makes sure Anna receives state-funded rehabilitation services, accessible furniture, special equipment and She confessed that it took a lot of work for her to achieve this and that there are more obstacles for parents of children with disabilities than proactive support.

No one will tell you what to do and where to go to get services for your child; you have to be very persistent and mentally resilient.

Liudmyla mentioned the importance of psycho-social support to both parents and children with disabilities in all stages of life. She said that a lot of families fall apart after a child with disabilities is born and that her husband and herself worked hard to preserve their union.

The war caused a huge step back in Anna`s development. She was terrified of the sound of the first air raid siren; when a missile hit a street around the corner from their house - she needed several sessions with a counselor to overcome the fear. Also, her annual rehabilitation had to be postponed because of the unstable situation in the region. The family is doing everything for Anna so that she can be fully included in society.

We believe it is our mission to teach the world how to perceive people with disabilities as equal to us all.

Olena and Egor

The full-scale russian invasion found Olena and her family completely unprepared: no food in the fridge, no cash or savings. Her husband was supposed to get his salary on Friday, February 25, 2022, yet the first missiles hit a day earlier. They have two boys, Egor, 15, and Glib, 11. The older one has a difficult form of epilepsy and psychosocial disability. They could not go down to the bomb shelter or evacuate using publicly available transportation because Egor becomes very aggressive in unfamiliar environments, a will start screaming and running away. After the first shock wore off, they decided to stay in their apartment in Kyiv.

I often think to myself that if something happens to Glib, my younger son, in Kyiv I will never forgive myself for the decision to stay. However, we cannot move to a safer place because of Egor. It requires a lot of resources and is virtually impossible.

Because of the enormous stress, Egor lost most of his teeth, and Olena struggled to find accessible dental care (and accessible transportation to get him to the clinic).

Before the war, Glib, Egor`s younger brother, helped Olena care for him while their father was earning the daily bread and butter. On February 24th their only breadwinner lost his job. The family did not have anything to eat for the first few weeks when Kyiv was constantly under shelling. The situation was extreme. Olena managed to connect to other parents of children with disabilities eventually and by word of mouth, they found scarce humanitarian relief.

Someone mentioned that there are some food and sanitary items available for free. We tried to access it.

Now, six months into the war Olena has adapted to the situation. Other than food the family needs special medicine for Egor and psychosocial support. She volunteers to help people who just like herself found themselves and their children with disabilities isolated from everyone else. They even adopted an abandoned war dog. Their reality turned upside down, life still goes on.

Hanna and Kostik

Hanna is a stay-at-home mom of three children. Her youngest son Kostik is 4 years old and has Down syndrome. Together with her husband, they live in Odesa. After the beginning of the war, they decided to stay at home - a tough decision that many families of children with disabilities had to make. Her husband also has a disability - very poor eyesight. Because of the war- related stress his vision dropped even more, yet the family cannot afford new glasses for him. At the beginning of the war, he lost his job as a mechanic and now is volunteering for the armed forces repairing armored vehicles

It was a hard choice, but we decided not to leave Ukraine. With limited resources and three children, we would struggle abroad. And for Kostik it would be difficult to adapt to a new place.

Their son Kostik is the same age as Lisa (a girl with Down syndrome killed in Vinnytsia by a russian missile on the 14th of July).

They were friends - Lisa and her mother came to visit a couple of years ago. Because of the war, Kostik could not continue regular sessions with speech therapists and physical therapists. The disability allowance is 2500 UAH. One rehabilitation session is at least 400 UAH. Hanna must think every day about where to find help to cover the basic needs of the family. Two other children are helping her care for the youngest. Despite the pressure to provide for the basics - such as food, clothes, and rental fee - Hanna is very aware that every day spent without intervention is a huge step back in Kostik`s development. Therefore, she is struggling to find solutions.

We did not receive much humanitarian aid. A couple of kilos of buckwheat and rice. Some cooking oil as well.

The main goal is both to survive and to support the country toward the final victory.

Snizhana and Dima

Snizhana is divorced and lives with her son Dima in Zaporizhzhya. Dima, who just turned 18, has severe visual impairments and an intellectual disability. Snizhana has a full-time job and is the only family provider. While she is working her mother and sister are helping take care of Dima. The young man has never studied in a school and until the age of 10 stayed home. Doctors even recommended that she admitted Dima to the institution. Dima is such a tender boy, he loves people and is very open to them.

I never understood why I have to give up my child in order for him to get services.

Then Snizhana found out about a rehabilitation community center called Prometheus. This is when Dima`s socialization started.

She regretted that Dima had no access to services like that since early childhood. Thanks to Prometheus' education and socialization camps Dima is now happier and much more independent. Now because of the war Prometheus has reduced the number of services they were providing. Still, Snizhana did not want to evacuate from a city close to the contact line because that would mean her losing a job and her son losing community services. She believes that because of his disability, he will not be able to get a paid job in Ukraine.

Dima constantly needs expensive medication. Any cash assistance from humanitarian funds is lifesaving for him.