Executive Summary

They gave us the children no one else wanted. No one wants something hard and difficult like this. They unloaded them from the train like dead bodies. - Director, Institution #1

Children who come here stay their whole life. This is their fate. There is no place else to go. This is a degradation of humanity. – Director, Institution #1

In late April 2022, Disability Rights International (DRI) brought a team of people with disabilities and family activists, including medical and disability service experts, to visit Ukraine’s institutions for children with disabilities. DRI visited three facilities for children aged six to adult, and one “baby” home for children from birth to age six. DRI finds that Ukraine’s children with disabilities with the greatest support needs are living in atrocious conditions – entirely overlooked by major international relief agencies and receiving little support from abroad.

Many children from institutions in Ukraine’s eastern war-torn areas have been evacuated.

In two of four facilities DRI visited. However, we found that children and adults with greater support needs were left behind in the institutions of western Ukraine while less impaired or non-disabled children from the same institution were moved to Poland, Italy, and Germany. Directors we interviewed report that children with greater impairments are being left behind in institutions in the east.

Children with greater impairments face the largest brunt of increased dangers. DRI investigators observed children tied down, left in beds in near total inactivity, and held in dark, poorly ventilated rooms that are so understaffed that they are enveloped in smells of urine and feces. Children rock back and forth or self-abuse as a result of years of emotional neglect. Staff have no resources or knowledge about how to respond to this behavior other than to restrain them for much of the day.

Children in Ukraine’s institutions are cut off from the love and care of families – perhaps the most damaging fact of institutional life that is as true today as it was before the war. Resources and staffing for medical care and support were stretched thin before the war. In some cases, basic care such as the treatment of hydrocephalus was lacking (e.g. observed in institution #2), leaving children to die a slow and painful death.

Since the war, the increased numbers in crowded institutions have produced more atrocious conditions. Immediate action is needed to identify where children are located in remote facilities -- and ensure they receive protection for their health and safety. As outlined in DRI’s recommendations below, international assistance must be provided in a manner that does not perpetuate Ukraine’s inherently dangerous and segregated system of institutions. Families of children with disabilities urgently need assistance to prevent new institutionalization. As soon as practical, Ukraine and international donors must work to help all children move from institutions to family placement. To make this possible, there must be a commitment on the part of Ukraine’s government from a policy of segregating children with disabilities to recognition of the right of every child to live and grow up in a family – as protected by the UN Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities (CRPD) which Ukraine has ratified.

1. Observations

DRI findings in early April 2022 raised concern that children with disabilities from war-torn areas of Ukraine are being left behind as children with no disabilities and limited support needs were being sent to other European countries. A report from UNICEF shows that children from facilities under the Ministry of Health and Ministry of Education are being evacuated. Noticeably absent from the information provided by UNICEF or the government of Ukraine are institutions under the Ministry of Social Policy – where children are placed who are considered to be disabled and “uneducable.” DRI targeted our investigation to identify the living conditions and immediate needs of these overlooked children.

A. Children with disabilities and greatest support needs left behind

The children with the most difficult problems from two institutions came here. Many of these children are bedridden. The children most able to move went abroad. – Director, Institution #2

The staff from the institution in the east dropped off the kids – and left here like rats from a sinking ship. – Director, Institution #1

At institution #1 (locations of facilities withheld for the safety of residents in a time of war), for example, there were ninety-six children and adults from age six and upwards. The facility received twenty-two of the girls with the greatest support needs from a facility in the Donetsk region, while children with few impairments went to Italy and Germany – as did the director. The girls arrived without medical records or any staff who knew anything about them, their lives or their medical history – let alone their names or ages. Weeks after they arrived, they were able to obtain limited medical records.

Institution #1 had to cut three staff this year as a result of pre-war planned budget cuts, and it received no new assistance for the children it was sent. “Focusing so much effort on the new children is 'slowing us down’ in our ability to respond to the children already here,” the director reported to DRI. According to medical authorities at institution #1, the high level of needs for medications has caused the facility to burn through their annual budget for medicine at three times the regular rate. Medical authorities do not know how they will obtain essential medicine when funds run out.

For more than 200 children and adults at institution #2, there are fifteen nurses, two part time doctors, and a dentist. The only psychiatrist on staff has joined the army and will not return until the end of the war. Staff from the previous facility also did not stay. The director says he was forced to hire seven new 'nannies‘ to care for thirty-eight new children and adults. Czech and Swiss organizations that provided help before the war continue to help now, but no new resources have come in. They receive some aid - such as food - that they cannot use and send it to other more needy institutions in the east.

We could put thirty kids in the auditorium if we had to. - Director, Institution #2.

At facilities #1, #2, and #3, directors reported concern about what would happen if they were asked to take more children. In institutions #1 and #2, despite already crowded conditions and rooms where beds are pushed end-to-end with no place to stand, all directors said that they would take more people if asked. At institution #3, the director is rehabbing a new building to expand the capacity of the institution.

B. Greater burden on staff and increased danger of neglect

The girls who arrived from Donetsk to institution #1 have greater support needs than the previous residents of the facility. The staff reported that they had “no idea what to do with them.” Due to the trauma of the move and lack of consistent treatment, staff report that the girls experienced large numbers of seizures. At the time DRI visited, fourteen teenaged girls were held in one room – all in bed mid-afternoon.[1] The room was itself a converted animal stable (rehabbed before the war), so it was dark and had windows on only one side. With one full-time staff person to care for fourteen girls and change diapers, the room smelled strongly of urine and feces. The room is barren, undecorated, without any personal effects, and so filled with beds it is impossible to do anything except lie or sit in bed.

The State does not give us enough money for medicine. We have to get it from volunteer donations. – Director, Institution #1

Staff said one girl had to be tied to her bed each night because she was so self-abusive (hitting herself, biting her fingers, putting her fist in her mouth and inducing vomiting), they did not know what to do with her (see in-depth profile of “V.”). Some children remain in restraints during the day. At institution #1, we observed two girls in the dining hall with their arms tied behind their back by fashioning straight-jackets with their shirt sleeves, forced to be spoon-fed because they could not use their arms. At institution #2, one boy was tied down and left flat on his back with a restraint band across his face, covering his nose and mouth.

We are fortunate here to be far from the fighting. But this does not mean we are not at war in our hearts. – Director, Institution #2

The directors of four institutions in the West visited by DRI uniformly expressed their personal readiness -- and the support of their dedicated staff – to make sacrifices for the war effort. Though DRI learned of budget cuts, some directors refused to speak of them, noting the enormous sacrifices being made by soldiers and civilians throughout Ukraine. One director said, “We will not complain. We have no needs.”

While the directors considered it their patriotic duty to make do with what the government provides, DRI investigators found that what was provided is entirely inadequate to provide for the basic health and safety of children or adults with disabilities at these facilities. In each of these facilities, DRI observed that the already limited staff were now being asked to care for a greatly increased number of children with more complex needs than they are accustomed or trained to care for. Thus, the lack of personal attention, lack of stimulus, and lack of essential care before the war is increased for children evacuated and children already at the facility.

Staff tell us their greatest needs are diapers and rubber sheets. I understand how overwhelmed they feel by the number of children who they need to change and keep clean. It must take all their time, and they have no resources left for care or other activities. So we see kids left in beds. But some staff seem unaware of the kinds of treatment and support the children are not getting. - Marisa Brown, RN

To an outside observer, children and adolescents in bed during the day or tied up in a chair may not seem terrible. But these kids need social interaction. They need stimulus. Sitting motionless, their arms and legs literally atrophy over time. And frankly, as their digestive systems become impacted, they are in pain and could require surgery. From both a psychological and physical perspective – it’s painful, dangerous, and it is slowly killing them. – Eric Mathews, MD

The impact of neglect is particularly great on children with the greatest support needs. In the absence of staff, they are simply left alone or tied down. The impact is also especially serious among the youngest children. DRI visited one baby home for 70 children from birth to age six before the war. This facility received thirty-five new children from the Kyiv region. The director said that some staff from the previous facility had remained to help care for these children – but this included no professionals, and medical staff reported that they were overwhelmed taking care of nearly 50% more children than before. Many international volunteers at the facility had fled since the start of the war (though two American volunteers remained). At this facility, there were only two staff on duty for two rooms of fourteen children.

Many of the facilities we visited were physically clean. But while staff were diligently cleaning physical space and changing diapers, the children received little direct attention or care. For children at the youngest age, the lack of opportunity to form a stable emotional connection to a consistent and committed care giver is likely to result in attachment disorder, a damaging developmental condition that is irreversible and can cause a lifetime of emotional and social impairment. At older ages, children can lose a month of cognitive development for every three they are placed in an institution. This is true for children placed with or without disabilities. At the baby home with the youngest children, DRI investigators were not allowed to visit the children from the east, but among the children already at the facility, we observed babies as young as three months oddly quiet and all alone in their cribs. Some of these children had begun to rock or swing their bodies rhythmically, or bite their fingers and poke their eyes – common forms of self-stimulation and self-abuse that come of emotional neglect. With one or two exceptions of loud screaming, most children did not cry or make any sounds as they laid in bed. This is learned behavior from young children who are not used to getting any attention.

At the facilities for older children and adults, we were able to observe the impact of years of neglect. We observed children whose arms and legs were thin from years of malnutrition. Even if there is adequate food, children who have lost hope in life suffer from what is called “failure to thrive” and stop eating – a condition that can lead to early death. Many of the children evacuated from Donetsk looked like they were 4, 5, or 6 years old, though we were told that they are teenagers.

The children are fed three times a day, but so many of the children across all three institutions appear to be grossly underweight and/or underdeveloped for their age. There are no nutritional supplements given to these children, and no assessment as to why they are not gaining weight as expected for their age. – Marisa Brown, RN

Among the children we observed at every institution, we also observed children whose arms and legs had become twisted and constricted due to lack of activity and sitting motionless for long periods of time with a lack of treatment for spastic cerebral palsy. At institution #2, DRI captured on video the sight of a fourteen year-old girl whose legs were wrapped in a “pretzel position” were locked solid as the tiny child was lifted to be repositioned by staff;

T. is a 14-year-old girl who is severely malnourished and was intensely crying for the 30-minute period the reviewers were in the room. She has extremely severe contractions resulting in scoliosis, kyphosis, and scissoring of her lower extremities. After 15 minutes of her intense crying out, the “nannie” picked her up (her body was literally as stiff as a board from her contractures) and moved her to the bottom of the bed while the nannie rearranged her bed linens. All the while the girl was being moved, she continued to cry out in pain. She has such a severe scoliosis that her right flank is touching skin-to-skin, placing her at risk for skin breakdown in that area. When asked what pain medication or muscle relaxant was available to her, the nurse replied that she wasn’t in pain, she was over-stimulated from our visit. This is torture. – Marisa Brown, RN

At institutions #1 and #2, staff report that there is no physical therapy for children with contractures in their arms and legs and no occupational therapy and education to children left in pervasive inactivity. The trauma of moving to new facilities is exacerbated by losing contacts with any staff to which they may have familiarity or emotional bonds. At institution #2, a young woman reported losing contact with two brothers when she left her phone behind at the previous institution. She has not received any help making contact and is afraid she will never see them again.

Children need to learn how to work. So they work in the garden to raise vegetables. They are taught to work. They do the duties of the staff. We can’t pay them because we do not have enough budget for more staff. – Director, institution #1

At facilities #1, #2, and #3, staff report that most children and adults work in a manner that is not compensated. It is not clear whether any resident works in a manner that is truly “voluntary” or could say no to the obligations placed on them by staff. At facility #3, the director proudly described how residents contributed to grow all vegetables and raise both pigs and cows. Youth moved from an institution in the east complained that they were being pressured to work constructing a new residential hall at the facility. They also complained about the loss of freedom to come and go from the facility that they had experienced at their previous institution. At institution #1, the director described how he would punish both staff and residents (over the age of 18) for such practices as smoking cigarettes. For such infractions, young women could be denied the “privilege” of leaving the facility. Residents of #1 informed investigators of their fear of authorities and their inability to speak to us openly during our visit.

The director of the baby house (institution #4) said that “not enough” direct care staff came with the thirty-five babies and toddlers who had been sent to his facility from the east. He also said that the facility needed rehabilitation specialists. The medical staff reported experiencing great pressure in taking care of the large number of children. They also said that, since there are no new adoptions during the war and other facilities were full, they are being forced to keep children older than the legally allowed age of six. The medical director spoke sadly of a seven year old child in a crib who would eventually have to be transferred to the facility for children and adults (institution #2 visited by DRI) where he would remain for the rest of his life.

The director of the baby house stated that there is a waiting list for placement of children at the facility, and that waiting list will simply have to get longer if they have no room. Many children on the waiting list are in hospital maternity wards or living with their own families. The director of #4 spoke proudly of the community-based services they provide to families. The existence of a waiting list and the enthusiasm of professionals for new community-based supports demonstrates the urgent need for support to families that could prevent new placements.

In addition to the impact on children, transfer from the east and placement in the new institution is also isolating for young adults. At institution #2, DRI encountered E:

Initially Y. was feigning sleep. She was one of 14 people in this dormitory room, but no one was near her age or intellectual capacity. She was able to answer a full range of questions posed to her. She initially said she did not want to leave this institution, because the staff are nice to her and she can talk to other people her age, although there were no other peers in the immediate area. When asked what she liked to do during the day, she reported that she had lived at home with her mother until the age of 16 years when her mother died. She never had the opportunity to attend school. She likes to play games on her phone, but she was not evacuated with her phone. She has two brothers, but she doesn’t know where they are, and she is not sure that they know where she is. She has received no phone calls since she was placed here. She had her brothers’ phone numbers in her phone, but the phone was not part of the possessions that were brought with her.

The vast majority of the people at institutions #1 and #2 (and many at #3) are considered uneducable by the government ministry charged with their welfare. The notion of certain people being “uneducable” due to an intellectual disability has been roundly rejected since the beginning of the 19th century.[2] The DRI team met K. at institution #1, who defies these expectations.

When we first met O, she was laying in her bed; and we were told that she was “bed-ridden” and non-verbal. Yet, once interaction was initiated, she became quite active and eventually initiated playing a game with one of the adults where she insisted that they trade shoes – she was successful, and she then proceeded to sing several songs and spoke in short phrases. Unfortunately, O. lives in an institution that provides almost no cognitive stimulation, and adult attention is restricted to people providing meals and hygiene, but with no routine attempts to communicate or understand the communication of any of the children.

A is thirty years old. She approached the visitors at institution #1 but was not one of the people transferred from the east. She bright-eyed and eager to share her English language skills:

“Hello! My name is A. Welcome.” When asked how she learned English she reports, “I learn English from watching TV. I want to come to America.” This reviewer is perplexed because she has been struggling to learn a few phrases of the Ukrainian language (without success). And yet this young woman, who was raised in a “baby home” and received no higher than a vocational education, is teaching herself English phrases and knows how to use them correctly. In fact, while A. has received some vocational education training when in her teen years, she is now made to work in the fields raising vegetables for herself and the other children and adults who live in her institution, even though she would like to pursue a different career and live in her own home and be able to make her own decisions.

On the second day of the reviewer’s visit, A. reported that she had to hide to speak with our team because she had been told not to speak to us, and she feared reprisals.

2. Institutions in Ukraine: an inherently dangerous place for children

After a three-year investigation in 2015, Disability Rights International released No Way Home: Exploitation and Abuse in Ukraine’s Institutions for Children. The report documented conditions of an estimated 100,000 or more children segregated from society and left to grow up without the love or care of a family. While many of these facilities were physically clean, children grew up in bleak conditions without the opportunity to form emotional connections with family through necessary and healthy development. Throughout these facilities, children were subject to chronic neglect and abuse, left in widespread inactivity without stimulation or opportunities to develop essential life skills – conditions that inevitably lead to increased cognitive and developmental disabilities.

The term “orphanages” is widely used by the public and among charities who believe they are helping children who have no place else to go. From the United States alone, there is an estimated $3 billion a year in faith-based charity donations to orphanages around the world. The term “orphanages,” however, is misleading as the vast majority of children in these facilities come from families.

Children in Ukraine’s “baby homes” and “orphanages” (referred to in this report as “institutions”) have at least one living parent or extended family. Children are placed in these facilities because of the poverty of the family or the lack of support for children with disabilities to live in the community. Children from Roma families, who are subject to widespread prejudice and often excluded from schools, are also heavily over-represented. Placements could have been prevented if protections for families and support in the community had been established. The current dangers faced by children in Ukraine’s institutions are vastly increased by the failure to protect families and ensure community inclusion of all children. A family caring for one child with a disability can usually get out of harm’s way. It is much more difficult to evacuate an entire institution of children or adults with significant support needs.

Within institutions, DRI observed denial of essential treatment for medical conditions with life-threating consequences (e.g. untreated hydrocephalus), and the prospect of being sent to life-time institutionalization. Children placed in institutions with unknown adults are exposed to bullying and sexual violence. DRI found that forced labor in institutions is the norm. Many children are subject to violence, disappearances, and human trafficking. As Russian forces massed on Ukraine’s border in 2014, DRI noted reports of children being taken from Ukraine’s institutions into Russia and (see Chicago Tribune op-ed of May 8, 2014) warned of the great dangers for children that would be faced in time of war – urging immediate action to close institutions and ensure family placement for all children.

During COVID, Ukrainian disability activists observed that many thousands of children disappeared from institutions, “sent home” to families. In theory, children were only sent to families who had maintained contact with a child. In practice, Ukrainian disability activists have alleged that children were sent to families who may no longer exist or never have expected to hear from these children again. These activists have alleged that there was no effort to check placements in advance or follow-up to determine whether children were safe.

In recent years, Ukraine has worked toward reforming its orphanage and institutional system for children and, in some areas, made great progress. A year ago, however, the government made a decision to exclude children with disabilities form its deinstitutionalization plans. Ukrainian and international disability rights organizations strongly objected. DRI, the European Network on Independent Living (ENIL) and Validity sent a joint contribution to the permanent representation of the European Union at the United Nations, in preparation of the EU – Ukraine Human Rights Dialogue. The submission, sent on 26 April, focuses on the situation of children in institutions and the status of the deinstitutionalization process in Ukraine. [3] In June 2021, the United Nations sent a Joint Communication of special rapporteurs and experts to the Government of Ukraine raising serious concerns about human rights violations in Ukraine’s institutions and objecting to the continuing policy of segregating children and adults with disabilities from society.[4]

3. Methodology, Terminology, Overview of System

While DRI’s current investigation included a small sample of an enormous institution system, our findings uniformly point to the greater dangers to which children with disabilities are subject when more children are packed into institutions with fewer resources and the same amount or less staff.

The DRI team consisted of experts with extensive international monitoring experience, including a nurse with experience in developmental disabilities, a physician, an attorney with experience in disability rights and human rights, and two Ukrainian disability rights activists with training in social work. DRI’s team includes three members who visited institutions and trained activists throughout Ukraine from 2012-2016 and co-authored DRI’s report No Way Home.

DRI conducted its investigation April 25-29th. The exact names and locations of institutions are left out of this report for the safety of residents in a time of war, but DRI will fully disclose this information to Ukrainian government and international human rights authorities. DRI took extensive photographic and video documentation in each facility to corroborate our findings and educate the public about the need for action to protect the rights of children and adults detained in these facilities.

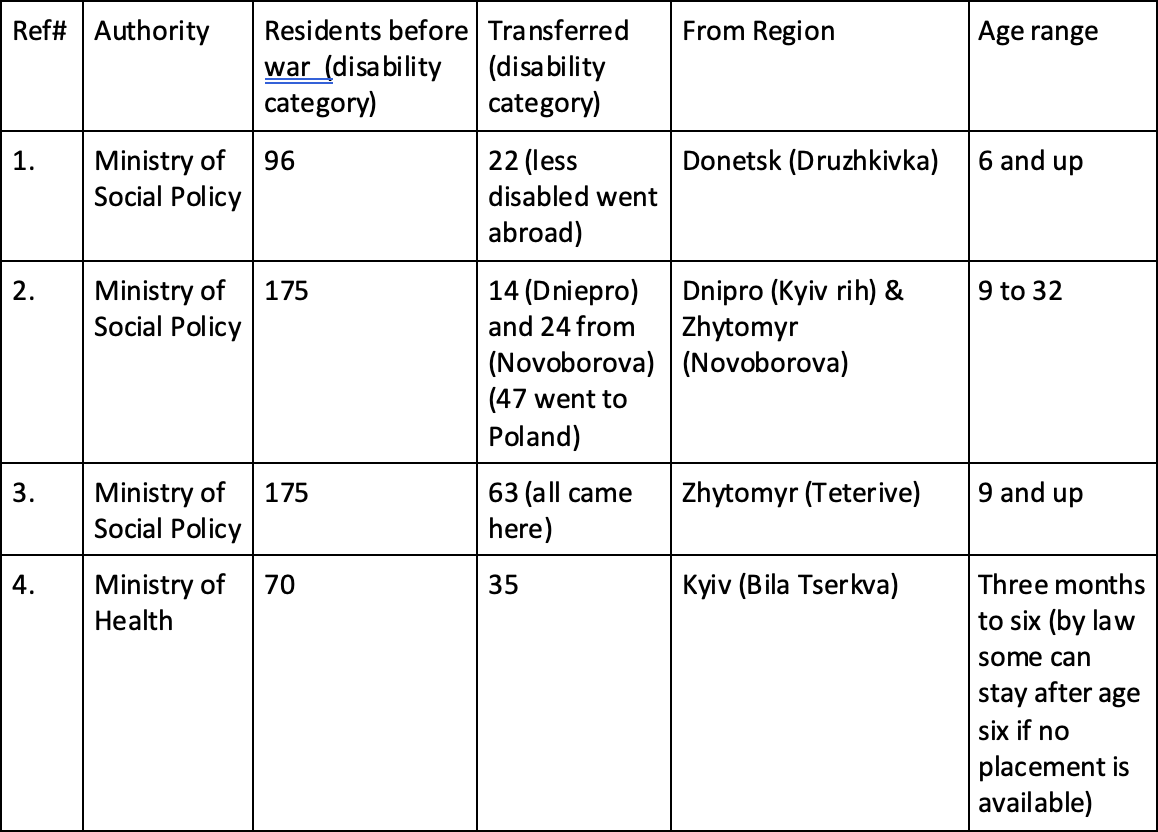

DRI visited the following facilities:

Note on Ukrainian disability categorization: The official system of disability categorization used in Ukraine’s system is unscientific, inaccurate, inconsistently applied, creates stigma, and perpetuates discrimination that may last a lifetime. At age four, children are evaluated by “defectologists,” and placed into one of four categories from lowest to highest level of disabilities. Children with the fewest disabilities and no mobility impairments are labelled level one and are usually placed in Ministry of Education boarding schools, where they receive a limited education segregated from all other children. Children with level two or higher are considered “uneducable” and are placed in institutions under the authority of the Ministry of Social Policy. Children from birth to age six are placed in “baby homes” under the Ministry of Health. Children and adults with a diagnosis of mental illness are placed in psychiatric facilities also under the authority of the Ministry of Health.

It is impossible to estimate the actual number of children in Ukraine’s institutions now or before the war. These facilities were administered by three different national ministries, local authorities, churches, and private entities. According to official government figures, there are more than 700 large institutions for children (also known as “orphanages”) in Ukraine. These figures do not include more than 1,000 smaller facilities or “group homes” that constitute institutions under international standards. There was no national oversight and no independent rights protection system to monitor conditions and protect rights, as required by CRPD article 16.

4. Recommendations to the International Community

The international community is providing generous levels of assistance and relief through many highly professional agencies since the start of the war. Some of these groups have, for the first time ever, created new disability policies or programs to reach children with disabilities. Specialized outreach programs have been established to help children with disabilities within Ukraine and among refugee populations. These programs are invaluable. Without targeted outreach to children in both large and small institutions, however, international assistance will inevitably overlook these children. Ukrainian authorities may be aware of the needs of some of these children, but directors at these facilities are not willing to speak out about their needs. Smaller institutions and so-called “group homes” (which may be for fifteen to twenty children) are not considered “institutions” by government authorities and are off the radar by Ukrainian authorities and international donors looking at institutions.

To guide international relief efforts, and to promote human rights oversight and monitoring, DRI recommends that funds be provided to independent non-governmental monitoring organizations with a specialty in this work. To preserve their independence and ability to speak out in cases of abuse that might be perpetrated by service providers, funds for monitoring should go to organizations that are not directly involved in service delivery or care of children.

Based on DRI findings, special attention must be focused on identifying and responding to the immediate safety and health needs of children the Ukrainian government has deemed to have the most “severe” disabilities. Children with the greatest support needs are receiving the least amount of international assistance and support and have the greatest immediate needs.

While Ukraine has made some progress in deinstitutionalization of children (mostly children without disabilities) since the release of DRI’s 2015 report, the country made a dangerous decision, contrary to its obligations under international law, to largely exclude children with disabilities from its deinstitutionalization program. DRI and our allies in the disability rights and children’s rights fields have objected to this. As cited earlier, the UN Special Rapporteur on Disability has raised concerns in a letter to the Ukraine government in June 2021. At every institution DRI visited, directors reported to DRI that they had every intention and expectation to continue maintaining their segregated institutions after the war.

Unless Ukraine changes its policy and practice of segregation on the basis of disability, international assistance to Ukraine’s social service system will inevitably be perpetuating segregation and discrimination in violation of international law. As DRI found in institution #3, there are already efforts to raise money to expand the size of institutions. International funding should be strictly barred from supporting infrastructure and expansion of institutions. The continued segregation of children and depriving them the opportunity to grow up with a family creates immediate and present dangers to all children. International support should protect the health, safety, and family inclusion of all children. Children (especially children with disabilities) moved abroad should not be returned to a system of segregation that will deprive them of their fundamental rights.

The way to protect children in Ukraine’s institutions is to ensure that aid goes directly to the child based on that child’s needs -- especially for older adolescents, youth, and adults responsive to their desires and preferences. In the immediate, that aid can help provide basic necessities, medical care, and staffing to keep children alive and cared for in the most humane process possible. As it becomes possible to seek family-based placements with biological parents, extended kinship networks, or if necessary supported foster care, that aid should be explicitly targeted for that purpose. The guiding principles of such funding should be used according to the well-established principle that “the money follows the person” – rather than supports the institution.

To be effective, DRI recommends that a significant portion of support be provided directly to disability-run and family-run advocacy organizations committed to protection of the rights of children with disabilities who support these reforms. Effective disability and family-run organizations in Ukraine do exist and should be supported for this effort. Long-term support and training is needed for these organizations to ensure that they are sustainable, that reforms are responsive to the needs of children with disabilities, and that an independent perspective is available to hold government authorities accountable to the enforcement of rights of children and adults with disabilities.

DRI recommends that the international humanitarian community create a pooled fund to respond to these immediate needs and work toward full family inclusion. To be effective, international donors must commit to at least a three-year time-table of support. Ultimately, the government of Ukraine must bear responsibility for taking on the task of supporting family placement in the country, but international aid can provide a powerful source of support to promote needed reforms. When the government fully engages in a commitment to enforce its legal obligations to protecting the right of children with disabilities to live and grow up with a family, international assistance can transition directly to support Ukrainian government efforts.

5. Legal Standards under International Law

International human rights and humanitarian law protects against discrimination on the basis of disability and guarantees the rights of children and adults with disabilities the same rights as enjoyed by all others. Many of the rights set out in the Universal Declaration of Human Rights are considered peremptory norms of international law which still apply in times of armed conflict, including the right to no discrimination, among others.[1]

The situation of children with disabilities in institutions in Ukraine, as outlined in this report, violates several of the rights and obligations recognized by the United Nations Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities (CRPD) including:

- The right of children with disabilities to community inclusion and to grow up in a family (Article 19 and 23). The CRPD Committee, in its General Comment No. 5, determined that “for children, the core of the right to live independently and be included in the community [Article 19] entails a right to grow up in a family.”[2]

- Detaining children with disabilities in institutions is a violation of their right to community which entails their right to grow up in a family. Failure to provide supports to families with children with disabilities to prevent separation, is also in violation of Article 23. Under the CRPD, it is the State’s obligation to ensure family reintegration, full community inclusion and supports and services for all children with disabilities and their families.

- The right to health (Article 25). In institutions visited, DRI observed denial of essential treatment for medical conditions with life threatening consequences. This is in violation of their right to health, can derive in a violation of their right to life (Article 10) and in the cases where the denial of medical result in severe suffering -such as the case of children with untreated hydrocephalus, it also amounts to a violation of the right not to be subjected to cruel, inhuman, and degrading treatment (Article 17).

- The obligation to provide supervision and oversight (Article 16). Under the CRPD, States have an obligation to monitor institutions where children and persons with disabilities are detained. DRI found that there is a lack of supervision and oversight of institutions, in violation of Article 16.

- International assistance must be used in a manner that complies with the CRPD, according the CRPD article 32. Thus, international assistance must not perpetuate institutionalization but must support the right of persons with disabilities to live in the community with choices equal to others. For children, this entails an obligation to support the protection of families and the placement of children in family-based care – not large or small residential facilities, institutions, or orphanages. International law permits support to institutions only to stop life-threatening conditions, torture, and ill-treatment. All other support must be directed toward family protection and placement of children.

Note on the limitation of international standards in humanitarian action:

The Inter-Agency Standing Committee Guidelines on the Inclusion of Persons with Disabilities in Humanitarian Action (IASC Guidelines) call for an identification of children living in residential facilities and to include them in family tracing and reunification when in ‘their best interest.’[3] DRI is concerned about this language which is not fully compliant with the requirements of the CRPD. The language leaves open the possibility of indefinite and continued institutionalization and leaving them out of family tracing. As noted above, the CRPD Committee, in its General Comment No. 5 recognizes the right of children to grow up in a family.[4] For children with disabilities in institutions, family tracing and reunification is a means to guarantee that right, and as such, they should be always included in those efforts. The IASC Guidelines must be updated to fully align with the CRPD to guarantee the right to grow up in a family for all children, particularly to protect children with disabilities detained in institutions.

Appendix A The Case of V. Girl at institution #1 evacuated from Donetsk.

V is a highly energetic and vivacious girl. She looks like she is five or six years old, but staff variously told us she was 14, 15, or 16. During our initial visit in mid-afternoon, she was sitting up in bed. She apparently craved stimulus and jumped out of bed to interact with visitors when we came into the room. Staff kept putting her back in bed. When DRI returned to the facility two days later in a surprise visit, V. was again placed in bed during the day – despite being awake and alert.

V. is self-abusive, hits herself, bites her fingers, and places her entire fist in her mouth. At times this induces vomiting. Research over several decades has demonstrated that self abuse can be initiated and maintained by multiple factors. Severe emotional neglect and lack of stimulation are among the causative and maintenance factors.[5] For the child, the pain of self-abuse can feel better than the lack of any stimulation at all. Unaware of what to do to help this girl, staff report that they tie down her arms and make her sleep in restraints every night.

Restraining a girl like this at night is dangerous. It almost certainly leads to additional psychological harm which could, in turn, result in more self-abuse. And keeping her physically restrained and in bed during the day, this girl is going to lose any chance to develop independent living skills or normal social interaction – much less the normal use of her arms. – Eric Mathews, MD

During the day, a young woman who is herself a resident (she looks to be in her twenties) of the facility provides one-on-one attention to the girl to stop her from self-abusing. This woman, who clearly enjoys her role in helping V., is not compensated in any way for her help. According to staff at the facility, this girl is a relative of one of the staff members at the institution. She was living at home with her mother. But when her mother got a divorce and started living with an alcoholic, living at home was dangerous for the girl. So, the staff member from institution #1 committed her to this facility.

There is absolutely no excuse for this woman to be locked up at this facility. It is highly likely, from the care we see she is providing to V, that she could live in the community and could probably hold down a job. – Marisa Brown, RN

This caregiving woman apparently seeks increased independence at the facility. Numerous times as we visited, she tried to leave the room and was prevented from doing so by direct care staff.

Staff report that V. has a seizure disorder (epilepsy). There were no medical records for her when she arrived from Donetsk and was having multiple seizures a day. Medical staff at institution #1 eventually obtained a summary of her medical records, but these records were incomplete. It is impossible to know whether seizures are new or have increased since her last placement. She is treated with carbamazepine and valproic acid. The latter is expensive for the institution and it is quickly burning through its medication budget at an unsustainable rate.

The facility does not have access to other appropriate anti-seizure medications that might be more expensive. According to medical staff, this creates avoidable dangers for V. and eleven of the other new arrivals at the facility who also require more complex medicine regimens. The chief doctor at institution #1 reports that the facility has used three months of their annual budget for medicine in the one month that the children from Donetsk have been there. Many of the other children are also having high levels of seizure. The doctor expressed that she is concerned and does not know what will happen to all children when the budget runs out.

The high level of seizures may be caused by the trauma of being moved and losing contact with trusted care givers. The seizures may also be caused by the lack of consistent medical care. While increased medical needs may be expected in a population that has just gone through such a difficult and rapid change, none of the medical conditions or disabilities we observed would justify institutionalization for any of these children. All of these children could be served in the community living at home with their families. – Marisa Brown, RN

Appendix B Statement by Marisa Brown, RN, Georgetown University Center for Child and Human Development

The most important thing they need is the love and attention of a family. One paid staff and one resident for all these children in bed must be overwhelming. There is little she can do other than change diapers and keep the children clean. The facility also needs:

- Occupational therapy to assess the children and work with staff to learn how to support their need for sensory stimulation;

- Speech pathology to maximize the children’s communication skills

- Play therapists to provide urgently needed play and learning stimulation.

- Special education experts – these children apparently receive educational services appropriate to their developmental needs.

- Physical therapy. This is a top priority for children in this room who urgently need assessments to develop treatment plans to stop the progress of additional, debilitating contractures and to determine if treatment can correct some of the severe deformities and provide much-needed pain relief. Many of the children we observed at the institutions #1 and #2 have severe contractures. This significantly hampers their ability to sit up and be mobile. This is essential to maintain adequate respiratory and digestive health and to cognitively be able to interact with their environment and express their needs. They don’t have the right equipment to provide them with support nor do they have staff to help them with the one-on-one attention they need.

What is impact of being in bed:

- Skin breakdown: Bed sores/pressure ulcers can get infected and even lead to bone infection and general sepsis.

- Lack of activity: Causes poor digestion which leads to constipation that may result in bowel obstruction that may require surgery and may even result in death. Most of the children/adolescents were incontinent because they had not had opportunity to be toilet trained. Their physical care requirements are extensive. Just keeping the room clean would take one staff person full time. The room was smelly when we came in BOTH times.

- Respiratory problems: Lying in bed for the majority of the day does not allow the lungs to fully expand.

- Possible use of medications to promote sedation: It is not clear how they keep them all in bed for such extended periods of time. This may be the result of learned behavior or they may be sedated.

- Cognitive: The pervasive lack of stimulation, lack of visual engagement, and forced immobility seriously and negatively impact child development. There is a premium placed on compliance versus exploring the environment and interacting with other children and adults. Even non-verbal children can learn through appropriate communication techniques, and there needs to be a recognition among staff that behavior is communication and non-verbal communication needs to be paid attention to. “Placement there will lead to increased cognitive disabilities.”

Overall, I do not believe that the staff of these institutions understand how to look at behavior as a form of communication. They are essentially trying to stop behavior – rather than observe and learn about what it tells them about the needs of these children.

Emotional impact – These children are emotionally stunted and becoming more emotionally damaged over time. They do not even interact with each other. There were almost no books. We saw one book which a girl was using for stimulation, just turning the pages. When books were introduced during the BBC visit, they were not appropriate for sensory level. Children began ripping pages. The facility needs board books, and books appropriate to the age and development of each child. Most of the children are using books for sensory stimulation just to flap the pages. Given lack of familiarity with the books, I am very confident stating that they were brought in for TV crew. On the other hand, I observed one girl who spent a good half hour being read to by one of the staff members. Sadly, when that staff member left at the end of her shift, no one else continued the activity. There is little to no stimulation of any kind. It calls into question what kinds of life these girls have had that they are even willing to sit for long periods of time.

- Sensory Stimulation: - Activating all five senses helps to calm, soothe, relax and energize children. No guided sensory activities or materials for the children to stimulate themselves were observed in any of the institutions or baby home:

- Touch: The skin is very sensitive to touch, and for most people this is a pleasant experience that provides comfort and relaxation. The only human contact observed in the institutions was related to caregiving or the restriction of movement. There were no materials available for the staff to enhance this sensory experience.

- Movement simulates the inner ear so we know where our bodies are in space – very helpful to promote balance. Movement also promotes strength and energy. There is a high premium in all of these settings to NOT move. Even outdoors at one of the facilities, the girls were expected to sit in place and there were no toys or sports equipment to encourage movement.

- Sight is our most powerful sense. Seeing things aids in memory and new learning. There are no decorations on the walls to provide this stimulation in the rooms housing the evacuated children and even for some of the permanent residents.

- Smell: the smell of food can stimulate the appetite. Instead, children are routinely exposed to odors associated with bodily excrement.

- Sound: Staff do not speak with the children or play music, particularly for the children who spend the majority of their day in bed or restrained.

This amounts to a total denial of human dignity. We saw this in the room of the children from Donetsk, but we also saw it throughout the institution. Upstairs, the director lined the girls and young women up and publicly humiliated them in front of the reviewers. He announced who was being punished for misbehaving. Who was losing privileges to leave the institution. He forced them to step forward at this comment, to sign or recite prayers – whether they wanted to or not.

It was particularly sad to see that two different songs were about the importance of mothers. It was cruel given the fact that these girls were never given the opportunity to have a mother.

Observations at Institution #3

Director said that they were in a richer institution before that. “They had flat a screen TV there, We don’t here.”

Most of the men at this facility do not even seem to have an intellectual disability. They are incorrectly diagnosed. And now these diagnosis will follow-them for a lifetime, limiting their movement, depriving them of opportunity, and opening them up to discrimination. Based on our interaction with them, noting how they speak and how they engage with people, they have good adaptive behaviors. There was an overrepresentation of children of Roma descent.

When we were outside, they were trying to bring us the young children. One of the young men who was describing the situation there did not display a disability. Many of the residents from the east said they had more freedom in their previous institution. Here they attend church but do not participate in other community activities. They were complaining bitterly of being forced to work to construct new dorms, and considering rebelling and not doing it. Good for them.

Other residents not from east were seen working to raise dairy cows, beef cattle, and pigs while maintain agricultural equipment.

Tetiana said they told her there was candy and food donated to them from the church for Easter. They were extremely upset because they were not allowed to keep the items given to them. They reported that the director took everything. In their previous place residence, they were able to keep their own property.

Staff presented the youngest child at the institution who reviewers met and videoed. He was self-abusive. His arms were being restrained by staff and other residents. He was provided no stimulation, positive behavioral support, or a helmet to prevent injury. He was watching other kids play soccer, but there was no attempt to help him engage in play or social interactions.

They brought us into a classroom where pre-adolescent boys were “relaxing” after lunch. “It is run like a senior citizen home. All this emphasis is on rest.”

All the facilities we visited had beautiful potted plants. At orphanage #2, they had newly planted gardens. The country may be at war, but life is going on.

Summary of Recommendation

To the Government of Ukraine:

- Move swiftly to provide resources adequate to protect the health and safety of children with disabilities in Ukraine, with an immediate focus on those children designated by the government as having “severe” disabilities;

- Identify the locations and the needs situation of children with disabilities living in large and small institutions, including children in so-called “group homes”;

- End policy of segregation - Reverse Ukraine’s disastrous and illegal policy excluding children with disabilities from its deinstitutionalization efforts;

- Recognize and enforce the right to family for all children – As a country that has ratified the CRPD, Ukraine is under a legal obligation to protect the right of children with disabilities to live and grow up with a family. Work to place all children within Ukraine and those returning to Ukraine with families;

- Provide support for family-based placements with biological parents, extended kinship networks or if necessary supported foster care;

- Do not extend policy of segregation to evacuees abroad - Do not limit receiving governments from practices of safe and appropriate family-placement of children who have been evacuated outside of Ukraine, so long as there is proper oversight, full protection of the child, and an ability to return the child to family-based care in Ukraine when it becomes safe to do so;

To the United States Government:

- Immediately raise as a matter of urgent priority with the Government of Ukraine the life-threatening and degrading conditions identified in this report;

- Provide funding to address these conditions as detailed below, including funding to disability-led responses. Establish a program of targeted funding to identify children in institutions and ensure that aid gets to those children is essential.

To the United States and other Foreign Government Funders and International Relief Agencies Working in Ukraine:

- Create targeted outreach to children with disabilities in Ukraine in both large and small institutions;

- Include outreach to children in so-called “group homes” of any size which are often off the radar screen of Ukrainian authorities and international donors;

- Fund independent non-governmental monitoring and family support organizations that specialize in this work. Monitoring funds should not be provided to organizations directly involved in service delivery or care of children due to inevitable conflicts of interest. Very effective disability advocacy and family-run organizations in Ukraine do exist and should be supported for this effort;

- Focus short-term relief on the immediate health and safety needs of those children identified by the Ukrainian government as having “severe” disabilities. Currently they are receiving the least assistance.

- Support deinstitutionalization of children with disabilities in Ukraine; do not support institutions or fund the expansion or building of infrastructure used to effectively warehouse children with disabilities.

- Create a pooled family protection and community inclusion fund to respond to the immediate needs of individual children and work toward full family inclusion. An effective and sustainable response will require at least a three-year commitment to bring about full community inclusion and family placement of all children in Ukraine’s institutions. Funding should “follow the child” rather than be provided in large lump sums to institutions. Disability and family-run organizations in Ukraine should have leadership roles in designing and implementing new family protection programs.

[1] When the facility knew we were bringing in a camera crew from BBC, they dressed the girls and placed them in the garden. Even in this environment, the girls from Donetsk were lined up on a bench and did not play or interact with one another. DRI investigators returned the next day and found the children again left in total inactivity in bed during the day in their room.

[2] History of Education Journal of the History of Education Society Publication details, including instructions for authors and subscription information: http://www.informaworld.com/smpp/title~content=t713599897 Disability, Education and Social Change in England since 1960 Felicity Armstrong Online Publication Date: 01 July 2007 To cite this Article: Armstrong, Felicity (2007) 'Disability, Education and Social Change in England since 1960', History of Education, 36:4, 551 - 568 To link to this article: DOI:10.1080/00467600701496849 URL: http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/00467600701496849

[3] See, for example, https://enil.eu/wp-content/uploads/2021/04/2021-EU_Ukraine_HRD-by-disability-rights-organisations.pdf

[4] UN Special Rapporteur, letter to Ukraine government, Ref AL UKR 5/2021, 30 June 2021, at https://spcommreports.ohchr.org/TMResultsBase/DownLoadPublicCommunicationFile?gId=26477 (last visited May 4, 2022).

[5] UNHCHR, “Protection of Human Rights in Armed Conflict” (2011), p. 10. Available at https://www.ohchr.org/sites/default/files/Documents/Publications/HR_in_armed_conflict.pdf; and Draft articles on responsibility of States for internationally wrongful acts, adopted by the International Law Commission at its fifty-third session in 2001, reproduced in Yearbook of the International Law Commission, 2001, vol. II, Part II (United Nations publication, Sales No. E.04.V.17 (Part 2)).

[6] UN Committee on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities, “General comment No.5 on Article 19: the right to live independently and be included in the community” CRPD/C/GC/5 (2017) para. 37. Available at https://www.ohchr.org/en/documents/general-comments-and-recommendations/general-comment-no5-article-19-right-live

[7] Inter-Agency Standing Committee, “Guidelines: Inclusion of Persons with Disabilities in Humanitarian Action” (2019), p. 156. Available at https://interagencystandingcommittee.org/system/files/2020-11/IASC%20Guidelines%20on%20the%20Inclusion%20of%20Persons%20with%20Disabilities%20in%20Humanitarian%20Action%2C%202019_0.pdf

[8] UN Committee on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities, “General comment No.5 on Article 19: the right to live independently and be included in the community” CRPD/C/GC/5 (2017) para. 37. Available at https://www.ohchr.org/en/documents/general-comments-and-recommendations/general-comment-no5-article-19-right-live

[9] Citation: Oliver, Chris. Annotation: Self-Injurious Behavior in Children with Learning Disabilities: Recent Advancements in Assessment and Intervention.Child Psychol. Psychiat. Vol. 30. No. 6, pp. 909-927, 199