“Our daughters are still lying there, waiting for justice.” Mother of girl that was killed at the fire

I. EXECUTIVE SUMMARY

On March 7, 2017, a group of girls, boys and teenagers protested the physical and sexual abuse, rape and trafficking that they were subjected to at the institution Hogar Seguro Virgen de la Asuncion (Virgen de la Asuncion), in Guatemala City, Guatemala. Virgen de la Asuncion was a public institution where up to 800 children were detained prior to these protests. The authorities of Virgen de la Asuncion called on the National Police to repress the protests. As a punishment, the girls who had protested were beaten and locked up in a tiny auditorium with a capacity for 26 people standing, without a bathroom and access to water,[1] where they were left to spend the night.

In the early hours of March 8, a fire broke out in the small auditorium, the chief of the National Police took 9 minutes to open the door, despite being right next to it with the keys in hand.[2] As a result, 41 girls died in the fire or afterwards due to the severity of their injuries. Fifteen girls survived, all of them with serious physical and emotional trauma. Disability Rights International (DRI) and the Human Rights Ombudsman (PDH for its Spanish acronym), got a precautionary measures order from the Inter-American Commission on Human Rights (IACH) requiring the state to guarantee the right to a family of the survivors, by adequately reintegrating to a family -their biological, extended family or a foster family.[3]

Yet, four years after the fire, survivors are still at risk. The State of Guatemala sent a report to the IACHR regarding the situation of Virgen de la Asunción survivors. This report provides clear data that shows that survivors face continuing and immediate threats to their lives and safety. The government has failed to take the steps necessary to protect survivors – much less provide them with the support and reparations they deserve as survivors of abuse at the hands of State authorities.

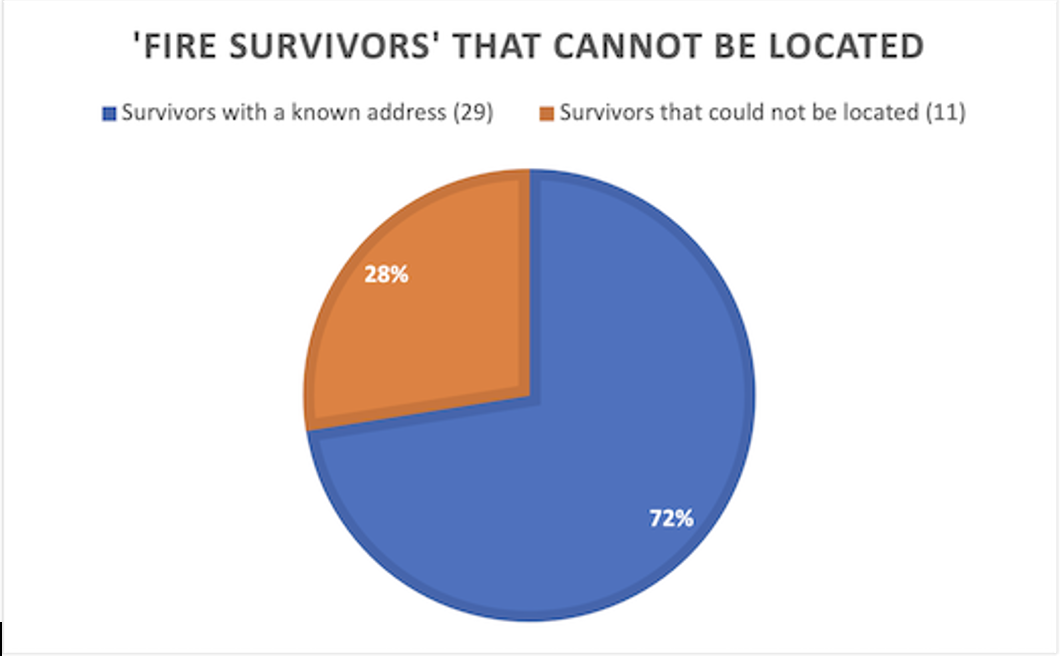

According to the State’s report to the IACHR, the government is following up on 40 -now- young women that refers to as “fire survivors.” According to the government’s information, it is currently unaware of the whereabouts of eleven of them. Some of these young women came close to dying themselves and were subject to the extreme trauma of witnessing their peers die in front of them; they should have received close and careful follow-up support, counselling, and reparations for the abuse they experienced at the hands of the State. The total neglect of the state to care for these young women leaves them open to further exploitation and abuse.

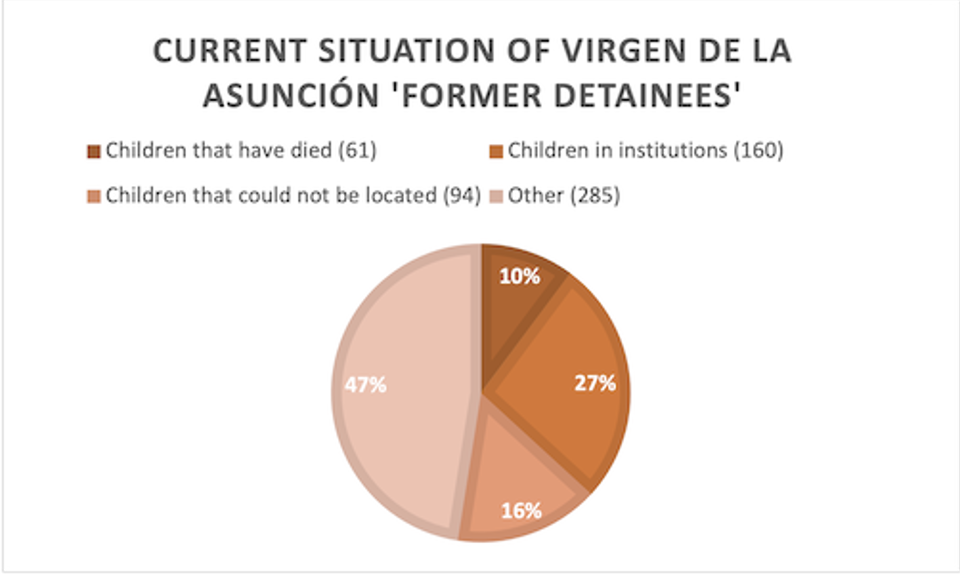

According to the government, there were 600 boys and girls detained at the facility (from now on referred to as ‘former detainees’) -though previous reports indicated that this number could be as high as 800. Of the 600 ‘former detainees’ 61 have died – a staggering statistic that makes up more than 10% of the entire population. Some of these boys and girls -some of whom are now adults- have died in violent circumstances. A few months after the fire, a 16-year-old teenager who had been detained in Virgen de la Asunción was murdered, allegedly by criminal gangs.[4]

Instead of providing support to ensure that the former detainees were given the support they needed to receive the care of a family – essential for the emotional safety and healthy development of any child – the state has allowed 160 former detainees to be placed in other congregate facilities all over Guatemala. Girls, boys and teenagers with disabilities have been disproportionately institutionalized, given the lack of alternatives and supports in the community.

The State has also failed the families who lost their daughters in the fire at the institution. Families have received no supports and face tremendous risks as they seek justice for their girls. Two mothers have been murdered after their daughters were killed by the fire at Virgen de la Asuncion. Another mother has suffered threats and has been physically abused, along with her children.[5]

The Ministry for Social Development has proposed plans to reopen the area of the fire, tear down the auditorium where the fire took place and build a monument instead. The families of the victims have opposed these plans and denounced them as a way to cover up the murders. They have demanded that the State focuses instead on ensuring that justice is served and that any decisions on the fate of the auditorium be made in conjunction with the victims and their families: “our daughters still lie there, waiting for justice.”

II. STILL AT RISK

1. Killing and intimidation of families and lack of access to justice

The State has failed the families who lost their daughters in the fire at the institution. Families have received no supports and face tremendous risks as they seek justice for their girls. Two mothers have been murdered after their daughters were killed by the fire at Virgen de la Asuncion. In June of 2018, Gloria Pérez y Pérez, the mother of Iris Yodenis León Pérez, was killed along with her husband Nery León and her 13-year-old daughter Nury León Pérez -who had also been detained at Virgen de la Asunción and witnessed the fire that killed her sister, Yodenis. The entire family was killed at their home in Sayaxché, Petén. More recently, in February of 2021, the mother of Wendy Anahí Vividor, María Elizabeth Ramírez, was killed. Another mother has suffered threats and has been physically abused, along with her children.[6]

The Human Rights Ombudsman's Office has expressed its concern given that, 4 years after the fired occurred, the death of the 41 girls and the serious physical and psychological harm caused to the survivors continue to go unpunished. The State had a special responsibility towards these girls as they were under its guardianship, putting the State in a particular position of guaranteeing the rights of these girls and adolescents.

Paula Barrios, coordinator of Women Transforming the World -an organization that is a complainant in the criminal case of Virgen de la Asunción, has indicated that “due to the pandemic and the appeals that have been filed, the case has been completely halted; the lack of commitment to ensure that the victims and their families obtain prompt justice is quite worrying.”[7]

The Inter-American Court has indicated that the right to justice entails that the State “must ensure the determination of the rights of the person in a reasonable time,”[8] since a prolonged delay “constitutes, in principle, by itself, a violation of judicial guarantees.” Given the prolonged delay in the criminal process, the State is failing to fulfill its obligation to guarantee the right to access prompt justice to the victims and the survivors.[9]

Nine people have been indicted, among them the Director of Hogar Seguro, but all of them have been indicted for 'minor' crimes that are linked to negligence rather than torture, alleged trafficking, and murder. According to the Bufete Juridico de Derechos Humanos (BDH), an organization that represents victims and their families:

“To this date there is little progress in the criminal process, none of the defendants have faced oral proceedings to clarify the facts and determine their responsibility. There is an exclusion of serious human rights violations in the events that occurred in Virgen de la Asunción, the crimes established in the present case are minor crimes and the repeated attempts to include serious crimes such as torture, executions and grave injuries have been continuously rejected, as well as the request to transfer the case to a Higher Risk Court.”[10]

The BDH also pointed out an inherent conflict of interest in the case in relation to the Procuraduría General de la Nación (PGN), a government agency acting in the criminal process as defendant and as the representative of 6 of the survivors of the fire. The Director of the Children's Unit at PGN, Harold Augusto Flores Valenzuela, has been indicted for the following crimes: mistreatment of minors, breach of professional duties, culpable homicide (manslaughter) and culpable lesions. All these crimes are due to his actions/omissions when and right after the fire started. Despite being one of the accused in the criminal case, the Director of the Children’s Unit is still at in charge of that Unit at the PGN.[11]

2. “Fire survivors” face exploitation, abuse and poverty

The State reported to the IACHR that it is following up on 40 young women aged 18-20 that it refers to as “fire survivors.” These group of young women include those 15 girls who were locked up in the auditorium when the fire started and who have turned 18.[12] In its report, the State attached the latest update on each of the ‘fire survivors’ files. According to these updates, eleven ‘fire survivors’ could not be located, social workers could not pin down an address for them and were unable to get any information on their whereabouts, their current situation, and their wellbeing. The ‘fire survivors’ are in an extremely vulnerable situation having been institutionalized, abused, and traumatized by the fire they survived but killed several of their peers. The fact that their whereabouts are unknown leaves them at great risk of further abuse and exploitation by traffickers.

As a general rule, children leaving residential care are extremely vulnerable and require follow-up support in accordance to international standards. For example, the European Office of the UN High Commissioner on Human Rights (UNHCHR) has found that “one in three children who leave residential care becomes homeless; one in five ends up with a criminal record; and in some cases, as many as one in ten commits suicide.”[13]

To avoid such dangers, the UN Guidelines for the Alternative Care of Children provides that “the reintegration of the child in his/her family should be designed as a gradual and supervised process, accompanied by follow-up and support measures that take account of the child’s age, needs and evolving capacities, as well as the cause of the separation.”[14] Where “the immediate family is unable to care for a child,” the UN Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities (CRPD) provides that States must “undertake every effort to provide alternative care within the wider family, and failing that, within the community in a family setting” art. 23(5).[15] Under CRPD article 19, children and adults with disabilities reintegrated to the community have a right to “community support services, including personal assistance necessary to support living and inclusion in the community.”[16]

The State owes an even greater duty to victims of exploitation and abuse through the provision of protective services. Under CRPD art 16(4), this shall include “all appropriate measure to promote the physical, cognitive, and psychological recovery, rehabilitation and social integration of persons with disabilities.” [17]

Guatemala has fallen woefully short of these obligations, leaving children and youth exposed to further danger. After the tragedy that killed 41 girls, the State created a life-long monthly pension of Q. 5,000 ($65 US) for the survivors to make sure ‘their basic needs are met.’[18] However, according to the State’s records, only 2 of the ‘fire survivors’ are receiving this pension. According to a news report from the beginning of the pandemic, at least seven fire survivors -some of them already mothers- are living in poverty, their families do not have jobs and they face hunger and possible eviction from their homes.[19]

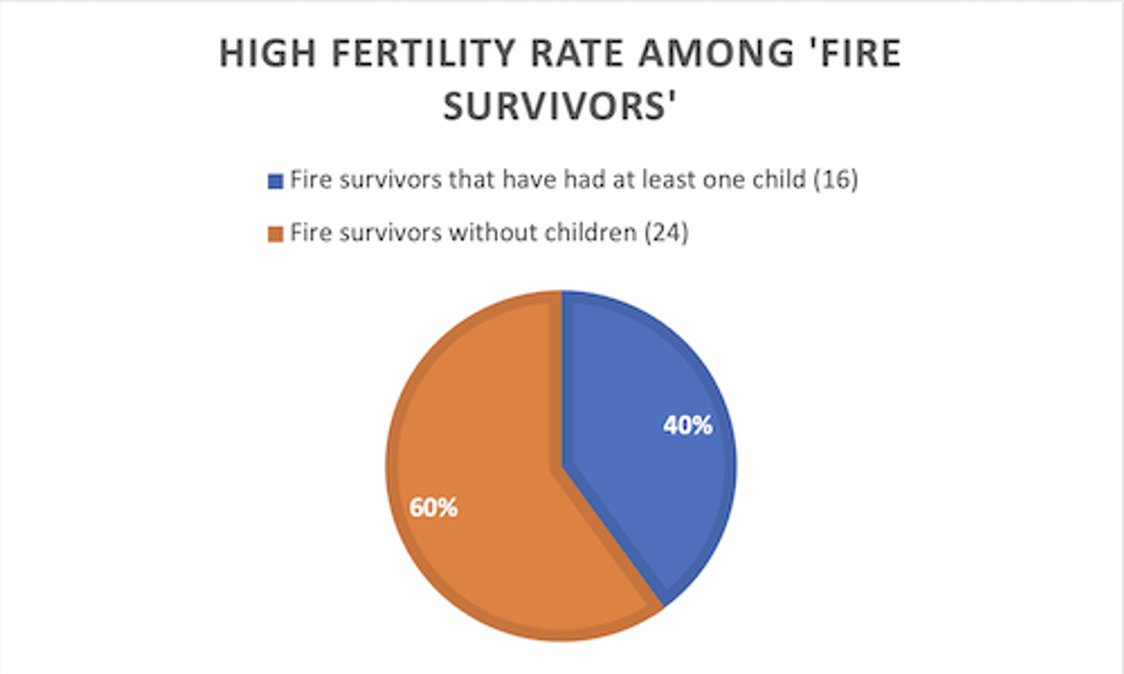

The State’s report indicates that 16 out of the 40 ‘fire survivors’ have had children -- which is 40% of the total. This is almost 5 times Guatemala’s adolescent fertility rate -at 84 births per 1,000 women aged 15-19 (8.4%).[20] The fact that such a high rate of survivors has had children coupled with the high risk of abuse they are at given that they have been institutionalized, should trigger a response from the State to guarantee that the survivors have access to all available recourses to denounce any situation of violence or exploitation that they may be facing; as well as access to information on family planning. Equally important, all survivors need to have full access to supports and services to raise their children and prevent and avoid at all costs family separation -and possible institutionalization of their children as a result

3. Death, institutionalization and disappearances of ‘former detainees’

According to the government, there were 600 boys and girls detained at the facility (from now on referred to as ‘former detainees’) -though previous reports indicated that this number could be as high as 800. Of the 600 ‘former detainees’ 61 have died, 160 are in private or public institutions and 94 cannot be located or have been placed under an Amber Alert.[21] That is, over half of the children who were detained at Virgen de la Asuncion have faced or are now facing grave danger: counting actual deaths, children who could not be located, and children denied the opportunity to live with family and placed in congregated settings.

The death rate of 10% (61) of ‘former detainees’ is extremely high, well above Guatemala’s mortality rate of 111 per 100,000 (0.1%).[22] This shows that this group of children and youth need extra protections and are at vastly greater risk than the rest of the population. This increased risk raises concerns for the rest of the children and questions on the State’s response to ensure an adequate, safe community reintegration as well as alternatives and supports for the children that were detained at the institution. There is an urgent need for further investigation to explain these deaths.

The fact that a fourth (160) of the former detainees remain detained in other institutions is in violation of their right to a family and to community living.[23] It is also in contravention of the IACHR’s precautionary measure request to reintegrate children to a family environment, in the community. Girls and boys with disabilities have been disproportionately institutionalized, given the lack of alternatives and supports in the community. In October 2018 DRI followed up on the “former detainees” with disabilities and found that 120 children were detained in 3 institutions created for children with disabilities from Virgen de la Asunción.[24] If these children with disabilities are still detained in these institutions, they would make up two thirds of the total number of ‘former detainees’ who are currently institutionalized.

All children who remain institutionalized remain at risk. The former Special Rapporteur on torture has found that children in residential or institutional care are at greater risk of mental health trauma, violence and abuse, and that the severe emotional pain and suffering caused by segregation and separation from their families may itself rise to the level of ill treatment or torture.[25] A report of UNICEF and the IACHR found that institutionalization exposes children to a greater risk of suffering various forms of violence, abuse, abandonment, and even exploitation in comparison with children who are living in other forms of alternative care:

“Violence in the institutions is the result of a number of factors associated with the normal operation of these institutions, such as the precariousness in sanitary and security conditions of the facilities, overcrowding, insufficient staff to provide adequate care to the children, social isolation and limited access to services, the implementation of disciplinary or control measures that involve violence, the use of force or treatments that, themselves, constitute a form of violence, such as unnecessary psychiatric medications, among others.”[26]

Institutionalization has long-term negative effects on children and adolescents. According to the former Rapporteur on Torture, Juan Méndez ““a number of studies have shown that, regardless of conditions in which children are held, detention has a profound and negative impact on child health and development. Even very short periods of detention can undermine the child’s psychological and physical well-being and compromise cognitive development.”[27] According to the UN:

“The most apparent immediate consequences of violence to children are fatal and non-fatal injury, cognitive impairment and failure to thrive, and the psychological and emotional consequences of experiencing or witnessing painful and degrading treatment that they cannot understand and are powerless to prevent. These consequences include feelings of rejection and abandonment, impaired attachment, trauma, fear, anxiety, insecurity and shattered self esteem.”[28]

Similarly, the report on World Violence against Children of the United Nations establishes that “effects of institutionalization can include poor physical health, severe developmental delays, disability, and potentially irreversible psychological damage. The negative effects are more severe the longer a child remains in an institution, and in instances where the conditions of the institution are poor.”[29] Due to the risk of structural violence that children and adolescents face in institutions, the Commission has recommended to the States that “design deinstitutionalization strategies for children who are in residential institutions.”[30]

Lastly, the government must fully answer for all the children for whom an amber alert has been issued. Needless to say, each and every child who is missing or has been deemed as missing is at great risk of abuse, trafficking and even death. The government must investigate each disappearance, find the missing children and ensure that comprehensive protection mechanisms are in place to prevent children from disappearing again.

III. IMMEDIATE MEASURES THAT THE STATE OF GUATEMALA NEEDS TO TAKE

As presented in this report, the rights of the children that were detained in Virgen de la Asunción are still being violated, and they are still at risk. It is imperative that the State takes immediate action to:

- Guarantee the safety of the families searching for justice for their daughters who were killed in the fire. The State must take immediate actions to stop the threats against family members seeking justice and fully investigate the murders and threats of family members to hold those responsible accountable.

- Locate survivors to ensure their immediate safety, housing, and medical needs, family re-unification and support, ensuring they can gain access to funds set aside for their support, offering them psychological counselling and emotional support, and providing protections against further abuse and exploitation at the hands of their former abusers and traffickers.

- Create emergency, supported foster care (substitute families) for any children who do not have families or who cannot safely return to their original family due to a history of child abuse, trafficking, or other immediate dangers.

- Interview survivors to learn of and protect against immediate threats – women and girls who have been trafficked and abuses are likely to be abused by the same individuals again or others who are interested in covering-up previous human rights violations; advocacy and legal representation is needed to ensure their rights and identify threats that the government can take action to counter these immediate threats.

- Investigate recent deaths and hold abusers accountable – until the investigation is complete and abusers have been held accountable, all survivors remain at risk.

- Independently review and create accountability for the trafficking and fire at the Hogar Virgen de la Asunción. Human rights advocates in Guatemala have taken the position that the investigation and prosecution of those responsible for the original fire and trafficking of girls at the facility was incomplete. The continuing high rate of deaths suggests that there may be ongoing efforts by cover-up their role in the previous tragedy. Given the historic role of government and service system authorities in those abuses, and further inquiry by authorities of the United Nations or the Inter-American human rights system is needed.

[1] Peace Brigades International, “A más de dos años de la tragedia del Hogar “Seguro”. https://pbi-guatemala.org/es/multimedia/art%C3%ADculos/más-de-dos-años-de-la-tragedia-del-hogar-“seguro”-entrevista-leonel-dubón

[2] Idem.

[3] Comisión Interamericana de Derechos Humanos “Resolución 8/17 Medida Cautelar No. 958-16: Hogar Seguro Virgen de la Asunción” (12 de marzo de 2017) https://www.oas.org/es/cidh/decisiones/pdf/2017/8-17MC958-16-GU.pdf

[4] La Hora, “Sobreviviente del Hogar Seguro fallece en un hecho de violencia” (5 de mayo de 2017) https://lahora.gt/sobreviviente-del-hogar-seguro-fallece-hecho-violencia/

[5] In these three cases, it has not been determined whether the violent deaths and threats form part of the criminal case regarding the Virgin of the Assumption Safe Home, in which eleven public officials are being tried for their participation in the acts committed on March 7 and 8, 2017. Iniciativa Mesoamericana de Mujeres Defensoras de Derechos Humanos, “GUATEMALA / Violent home break-in, threats, and attacks against children of Elsa Siquín, mother of one of the 56 victims of Virgin of the Assumption Safe Home Massacre” (21 de marzo de 2021) https://im-defensoras.org/2021/03/whrd-alert-guatemala-violent-home-break-in-threats-and-attacks-against-children-of-elsa-siquin-mother-of-one-of-the-56-victims-of-virgin-of-the-assumption-safe-home-massacre/; Republica “Matan a la familia de una menor víctima del Hogar Seguro” (9 de julio de 2018) https://republica.gt/2018/07/09/familia-victima-hogar-seguro-peten/

[6] Idem.

[7] Women’s Media Center, “ 41 crosses, 56 lives: The struggle for truth and justice two years on from the Hogar Seguro Virgen de la Asunción fire” (March 5, 2019) https://www.womensmediacenter.com/women-under-siege/41-crosses-56-lives-the-struggle-for-truth-and-justice-two-years-on-from-the-hogar-seguro-virgen-de-la-asuncion-fire

[8] Corte Interamericana de Derechos Humanos, Caso Bulacio Vs. Argentina, 2003. Párr 114

[9] Corte Interamericana de Derechos Humanos, Caso Hilaire, Constantine y Benjamin y otros Vs. Trinidad y Tobago, 2002.Párr 145

[10] Bufete de Derechos Humanos, Informe a la Comisión Interamericana de Derechos Humanos, para. 7

[11] Id., para. 9

[12] The government report does not differentiate this group of "40 survivors of the fire" between those who were in the auditorium when the fire occurred. Nor does it clarify where this number comes from and how it was determined that these 40 girls and women were considered the "survivors of the fire."

[13] United Nations Office of the High Commissioner on Human Rights, Regional Office for Europe, The Rights of Vulnerable Children Under the Age of Three: Ending their Placement in Institutional Care (2011), p. 19.

[14] Asamblea General de la Organización de las Naciones Unidas, “Directrices sobre las modalidades alternativas de cuidado de los niños” (24 de febrero de 2010) https://www.acnur.org/fileadmin/Documentos/BDL/2010/8064.pdf?file=fileadmin/Documentos/BDL/2010/8064, para. 52

[15] ONU, Convención sobre los Derechos de las Personas con Discapacidad, Articulo 23.5 https://www.un.org/esa/socdev/enable/documents/tccconvs.pdf

[16] Id. Artículo 19(b)

[17] Id. Artículo 16(4)

[18] Procuraduría General de la Nación, “Oficio No. 1,066-2020 Informe Solicitado de jóvenes sobrevivientes del Hogar Seguro Virgen de la Asuncion” (23 de Noviembre de 2020)

[19] Prensa Comunitaria “Menores de edad sobrevivientes del incendio del Hogar Virgen de la Asunción no reciben la pensión vitalicia desde enero” (6 de mayo de 2020) https://prensacomunitar.medium.com/menores-de-edad-sobrevivientes-del-incendio-del-hogar-virgen-de-la-asunción-no-reciben-la-pensión-b8f6e9b000c6

[20] Panamerican Health Organization, “Adolescent and Youth Health 2017 Country Profile” https://www.paho.org/adolescent-health-report-2018/images/profiles/Guatemala-PAHO%20Adolescents%20and%20Youth%20Health%20Country%20Profile%20V5.0.pdf

[21] Procuraduría General de la Nación, “Oficio No. 105-2020-PNA-PGN-mm” (23 de Noviembre, 2020)

[22] Panamerican Health Organization, “Adolescent and Youth Health 2017 Country Profile” https://www.paho.org/adolescent-health-report-2018/images/profiles/Guatemala-PAHO%20Adolescents%20and%20Youth%20Health%20Country%20Profile%20V5.0.pdf

[23] CRPD Articles 19 and 23

[24] Disability Rights International, Colectivo Vida Independiente de Guatemala “Still in Harm’s Way

International voluntourism, segregation and abuse of children in Guatemala” (July 16, 2018), p. 5

[25] ONU, Informe del Alto Comisionado de las Naciones Unidas para los Derechos Humanos, A/HRC/34/32 (31 de enero de 2017), párr. 30.

[26] UNICEF, Comisión Interamericana de Derechos Humanos, supra nota 14, pág. 3, párr. 11.

[27] ONU, supra nota 25, párr. 33.

[28] Paulo Sérgio Pinheiro, “The world report on violence against children”, pág. 189, https://www.unicef.org/violencestudy/I.%20World%20Report%20on%20Violence%20against%20Children.pdf (Última visita 23 de abril de 2018).

[29] Id., Pag. 189

[30] CIDH, RESOLUCIÓN 21/2018 Medida cautelar No. 975-17 Niños, niñas y adolescentes del Centro de Reparación Especializada de Administración Directa de Playa Ancha respecto de Chile, 15 de marzo de 2018 para. 23