BEHIND CLOSED DOORS:

Human Rights Abuses in the Psychiatric Facilities, Orphanages and Rehabilitation Centers of Turkey

Released in Istanbul, Turkey September 28, 2005

This report was funded by the Open Society Institute, the Ford Foundation, the Public Welfare Foundation, and the John D. and Catherine T. MacArthur Foundation

Authors

Laurie Ahern, Associate Director, Mental Disability Rights International (MDRI)

Eric Rosenthal, JD, Executive Director, MDRI

Research Team & Co-Authors

Elizabeth Bauer, MA, Michigan State Board of Education

Nevhiz Calik, JD, Law Clerk, Superior Court, Alaska

Mary F. Hayden, Ph.D., Social Worker, Independent Consultant

Arlene Kanter, JD, LLM, Meredith Professor of Law, Co-Director, Center on Disability Studies, Law, and Human Policy, Syracuse University College of Law

Şehnaz Layikel, Human rights advocate, MDRI representative in Istanbul

Dr. Robert Okin, MD, Chief of Psychiatry, San Francisco General Hospital

Clarence Sundram, JD, President of MDRI & Special Master, United States District Court, District of Columbia

Translation

Pınar Asan

Şehnaz Layikel

Supporters from Turkey

Human Rights Agenda Association

Federation of Schizophrenia Associations

Association for Protecting Trainable Children

Mesut Demirdoğan, Director of Friends of Schizophrenia Association

Aysel Doğan, Director of Schizophrenia House Friendship Association

Yalçın Eryiğit, Director of İzmir Schizophrenia Solidarity Association

Pinar Ilkkaracan, MA, psychotherapist, researcher & writer

Serra Müderrisoğlu, Assoc. Prof., Bogazici University, Department of Psychology

Abide Özkal, Director of Support for Special Children Association and mother of a child with developmental disability

Murat Paker, Assoc. Prof., Istanbul Bilgi University, Department of Psychology

Harika Yücel, Psychologist

TABLE OF CONTENTS

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

EXECUTIVE SUMMARY

CONCLUSIONS

SUMMARY OF RECOMMENDATIONS

TURKEY’S INTERNATIONAL LEGAL OBLIGATIONS

PREFACE: GOALS & METHODS OF THIS REPORT

- I. ABUSES IN PSYCHIATRIC INSTITUTIONS

- II. ABUSES IN REHABILITATION CENTERS & ORPHANAGES

- III. IN THE COMMUNITY: NO ALTERNATIVES TO INSTITUTIONS

- IV. LACK OF LEGAL PROTECTIONS & OVERSIGHT

RECOMMENDATIONS

ENDNOTES

APPENDIX 1 PHOTOS

APPENDIX 2 CHILDREN OF SARAY: ANALYSIS OF PHOTOS

- RECOMMENDATIONS – CHILDREN WITH INTELLECTUAL DISABILITIES

APPENDIX 3 THE CASE FOR A TURKISH MENTAL HEALTH LAW

- ASSESSMENT OF TURKISH PSYCHIATRIC ASSOCIATION’S DRAFT LAW

APPENDIX 4 LETTERS OF SUPPORT

Acknowledgments

Mental Disability Rights International (MDRI) is indebted to many people in Turkey who generously gave their time to provide observations and insights about the human rights concerns of people with mental disabilities in Turkey. The people who assisted the MDRI investigators include people who use or formerly used mental health services in Turkey, members of their families, mental health service providers, members of the psychiatric profession, institutional staff, and government officials.

MDRI’s work in Turkey would not have been possible without the extensive assistance of human rights activists, people with mental disabilities and their families and service providers in Turkey. They not only provided us with intimate details of their lives and the treatment they received, they also provided invaluable background about the politics and culture of Turkey. To protect their privacy, we do not acknowledge them by name here.

During the course of our investigations, we were greatly assisted by Dea Pallaska O’Shaughnessy with translation and fact-finding. Additionally, former MDRI staff member Abe Rafi and advisor Mary Hayden assisted with the investigation in Turkey and provided us with valuable information used in this report.

In the United States, we appreciate the work of Lazarina Todorova for editing the video version of this report. Christopher Hummel, MD, provided invaluable medical background research. Sam Gil provided assistance in social science research. Holly Burkhalter, John Heffernan, and Anne Cooper of Physicians for Human Rights provided helpful background on press strategy. Gretchen Borschelt and Alison Hillman de Velásquez reviewed and proofed the entire report. Jennifer Conrad, a law student at Syracuse University, reviewed and corrected footnotes and legal citations. Also, special thanks to Pınar Asan who helped us with outreach to the Turkish press.

Lisa Newman reviewed the report and provided help with outreach to the press. Her emotional support and deep commitment were essential to the success of this work. Special thanks to Lisa’s parents, Grace and Bud Newman, who traveled to Washington, DC to help with child care during each of MDRI’s investigative missions.

We would like to thank the Ford Foundation, the Public Welfare Foundation, the John D. and Catherine T. MacArthur Foundation and the Open Society Institute for funding this research. This work would not have been possible without their support.

Executive Summary

Behind Closed Doors describes the findings of a two-year investigation in Turkey by Mental Disability Rights International (MDRI) and exposes the human rights abuses perpetrated against children and adults with mental disabilities. Locked away and out of public view, people with psychiatric disorders as well as people with intellectual disabilities, such as mental retardation, are subjected to treatment practices that are tantamount to torture. Inhuman and degrading conditions of confinement are widespread throughout the Turkish mental health system. This report documents Turkey’s violations of the European Convention for the Prevention of Torture (ECPT), the European Convention on Human Rights (ECHR), the UN Convention on the Rights of the Child (CRC) and other internationally accepted human rights and disability rights standards.

There is no enforceable law or due process in Turkey that protects against the arbitrary detention or forced treatment of institutionalized people with mental disabilities. There are virtually no community supports or services, and thus, no alternatives to institutions for people in need of support. As a result, thousands of people are detained illegally, many for a lifetime, with no hope of ever living in the community. Once inside the walls of an institution, people are at serious risk of abuse from dangerous treatment practices. In order to receive any form of assistance, people must often consent to whatever treatment an institution may have to offer. For people detained in the institution, there is no right to refuse treatment. The prison-like incarceration of Turkey’s most vulnerable citizens is dangerous and life-threatening.

Some of the most egregious human rights violations uncovered by MDRI include:

Psychiatric Institutions

- Arbitrary detention of every person – In the absence of any enforceable law or procedures for independent judicial review of commitment, every person in Turkey’s psychiatric facilities are detained arbitrarily and in violation of international law;

- The inhumane and pervasive use of electroconvulsive or “shock” treatment (ECT) without the use of muscle relaxants, anesthesia, and oxygenation (referred to as “unmodified” ECT) in state-run institutions – ECT is a psychiatric treatment whereby electricity is administered to the brain and is thought to alleviate certain conditions that do not respond to more conventional treatment. However, in its unmodified form, it is extremely painful, frightening and dangerous and violates the European Convention for the Prevention of Torture. The World Health Organization (WHO) has called for an outright ban on unmodified ECT.

I only had ECT one time. It was the first and the last time. They hold you down, they hold your arms, they hold your head and they put cotton in your mouth. I heard them say 70 to 110 volts. I felt the electricity and the pain, I felt like dying. – 28-year-old former Bakirköy psychiatric patient

- The use of ECT as punishment - The director of the ECT center at Bakirköy Psychiatric Hospital, one of the largest institutions in the world, told MDRI investigators that they do not use anesthesia because “patients with major depression feel that they need to be punished.” Patients cannot refuse this treatment and they are frequently lied to and told they are getting an x-ray. Terrorized people are commonly dragged into the ECT room in straitjackets and are forcibly held down by staff during the procedure. ECT without the use of anesthesia and muscle relaxants violates all internationally accepted medical standards. Other psychiatrists observed that, because there are no standards on the use of ECT in Turkey, ECT is abused and used as punishment.

We use ECT for people with major depression. Patients with major depression feel that they need to be punished. If we use anesthesia the ECT won’t be as effective because they won’t feel punished. – Chief of ECT Center, Bakirköy

- The use of ECT on adolescents and children – The WHO has stated that there are no clinical indications for the use of ECT (even with anesthesia) on children and the practice should be banned in all cases. Psychiatrists report that ECT is regularly administered to adolescents and on rare occaisions on children. In Turkey, children as young as nine years old are administered ECT without anesthesia.

- Over-use of ECT – ECT is massively overused in Turkish psychiatric facilities in cases for which there is no clinically proven justification. ECT is used for the convenience of institutional authorities when more appropriate services in the community are unavailable. The over-use of ECT exposes thousands of people to unnecessary, frightening and dangerous experiences and violates the Turkish government’s own public commitments to the European Committee for the Prevention of Torture.

Rehabilitation Centers and Orphanages

I love my daughter, but I hope she dies before I do. I do not know what will happen to her after I die and can’t take care of her any longer. I do not want her ever to have to live in the institution. – Director of a private school for children with mental disabilities

- Starvation and dehydration – MDRI observed bedridden children, unable to feed themselves due to their disability, left inadequately fed and without assistance by staff. Investigators observed children emaciated from starvation. Staff reported children dying from starvation and dehydration.

Many of the children could not feed themselves. Some were struggling to hold onto or reach the bottles and much of the contents spilled out onto beds or wasn’t eaten. A little girl, who looked to be about 2 years old, was crying and squirming in her crib. A full bottle of formula was lying in the corner of her crib, just out of reach. I watched for over an hour, and no one came to feed her. She would have had nothing if I hadn’t eventually helped her.

Over the course of a number of feedings, I watched as staff came quickly into the room, dropped off bottles, and then picked up the bottles as they left the room. If a child could not pick up the bottle to eat or drink, she starved. - MDRI investigator

- Lack of rehabilitation and medical care – There is a broad lack of rehabilitation and physical therapy for children and adults with disabilities detained in orphanages and rehabilitation centers. Left to languish for years in a state of total inactivity, placement in these facilities is likely to contribute to a person’s disability. Children’s arms, legs, and spines become contorted and atrophy from the lack of activity or physical therapy. The effect of living without loving care-takers or any form of stimulation causes some children to become self-abusive. Rehabilitation centers offer no assistance for self-abusive children other than to tie them down. According to staff at one facility, children with the most severe physical and mental disabilities are denied medical care when they become ill and are left to die.

Nurses come to the units and stand in the doorway. They ask workers if there are any sick children, they just yell in. The workers always say no even if the children are very ill. When children get sick, they are no longer bathed and are not allowed to be taken out of bed. They are tied into their beds at times. If children are not taken care of, they do die. One is dying now. - Saray staff

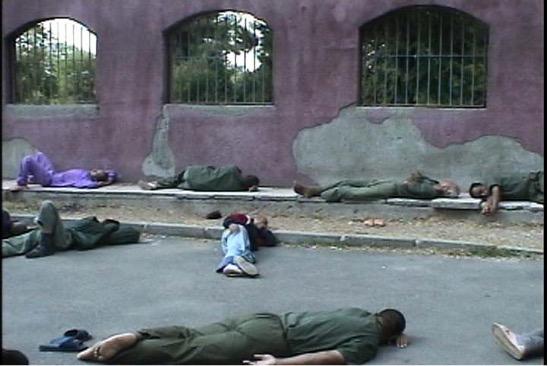

- The use of physical restraints and seclusion on both children and adults – MDRI observed children tied to cribs and beds, some of them permanently restrained. Four point restraint, that is, legs and arms tied to the four corners of the crib or bed, is also used. Children who scratch or hurt themselves – a reaction to the mind-numbing boredom they are forced to endure – were found with plastic bottles permanently duct taped over their hands. MDRI investigators also found a young child locked in a tiny room alone. At another institution we observed a small seclusion room with no toilet, reeking of urine.

Personnel get cut in half on the weekends. On some of the units, children are restrained. If you let them go, they go after the quiet children. They are just bored and frustrated. So they are restrained all the time. [The children] are between 7 and 15 years old. – Saray staff

Lack of community care

- People with mental disabilities and families are abandoned – Community-based care and supports are almost entirely unavailable for people with mental disabilities. Throughout the world, it has been demonstrated that community programs can help people with mental disabilities (either psychiatric or intellectual) live fully as part of society, to enjoy relations with family members and friends, and to take advantage of educational opportunities, work and cultural life. Without such support, people with mental disabilities in Turkey are often segregated from society in institutions or their own homes. People with mental disabilities may have no choice but to depend on families for a life-time. Without adequate support, family members often become overwhelmed and impoverished.

Conclusions

In the absence of an enforceable mental health law, everyone detained in Turkey’s institutions is illegally and arbitrarily detained as a matter of the European Convention on Human Rights (ECHR). Within institutions, Turkey subjects its citizens with mental disabilities to a broad range of serious human rights violations. The use of unmodified ECT is the most common and dangerous human rights violation documented by MDRI. Even for children and adults who do not receive ECT, detention in a public psychiatric facility or a rehabilitation center is a degrading and dangerous experience. The lack of active treatment and rehabilitation at these facilities for thousands of children and adults with mental disabilities leaves them segregated from society with no hope of returning to normal life. The total inactivity and social isolation experienced in these facilities presents a threat to their development and psychological well-being. Such custodial detention violates the right to health of all people so detained.

The lack of community-based mental health services creates enormous pressures on in-patient psychiatric facilities and undermines the treatment and care they can provide. By unnecessarily filling inpatient beds with “chronic” patients, there is a shortage of resources for people in need of acute care throughout the system. Large state facilities throughout Turkey are overwhelmed. As a result, people most in need of treatment – individuals undergoing an acute psychiatric crisis – are often deprived of the attention and care they need. Staff at two state psychiatric facilities reported that ECT is commonly used because it appears to produce a quick alleviation of symptoms and patients can be returned to the community. Yet the provision of ECT in 20-40% of acute cases is totally inappropriate. Its efficacy for a wide variety of indications is unproven or contra-indicated by internationally accepted standards of psychiatry. Many patients reported to MDRI that they would do or say anything to be discharged to avoid being subjected to ECT.

For people subject to the most extreme abuses – the long-term use of physical restraints, the coerced use of unmodified ECT, the lack of protection against violence, and the denial of medical care – detention in a facility can be painful, dangerous and life threatening. Such practices constitute the most extreme forms of inhuman and degrading treatment prohibited by international law. People subjected to unmodified ECT as a form of punishment are being subjected to torture.

The structure of Turkey’s public mental health and social service system segregates people with mental disabilities from society and puts large numbers of its citizens with mental disabilities at risk of these abuses. The sole reliance on long-term custodial facilities is contrary to internationally accepted human rights standards as well as widely recognized best practices in mental health. At a gathering of European governments convened by the WHO in January 2005, Ministers of Health of the member states for the European Region affirmed their commitment to “develop community-based services to replace care in large institutions for those with severe mental health problems.”1 They also agreed to adopt mental health legislation to protect against discrimination and “end inhumane and degrading care.”2 European governments have committed themselves to “offer people with mental health problems choice and involvement in their own care, sensitive to their needs and culture.”3 Turkish mental health services do not meet these standards.

As Turkey applies for membership in the European Union, it is under an obligation to take action to harmonize its laws and policies to meet European standards and to protect basic human rights of its citizens with disabilities. A major new commitment is urgently needed on the part of the government of Turkey to enforce these human rights — to protect people with mental disabilities against abuses within institutions and to develop positive programs to ensure their full integration into Turkish society.

Summary of Recommendations

MDRI recommends that the government of Turkey take immediate action to end conditions that are dangerous and life-threatening. Practices that constitute torture or inhuman or degrading treatment must be immediately terminated. The government of Turkey should:

- Ban the use of unmodified ECT in all circumstances;

- Establish guidelines to ensure that ECT is only used with appropriate medical safeguards, is only used in limited circumstances and within internationally accepted and proven indications for its use, and is never used without the free and informed consent of the individual subject to the treatment;

- Stop the use of restraints and seclusion as a substitute for rehabilitation and lack of staff;

- Ensure the availability of adequate food, staffing, and medical care to protect the basic health and safety of everyone detained in an institution;

- Create oversight mechanisms to ensure that physical and sexual abuse in institutions is terminated;

- Create a system of family support and supported foster care to ensure that all children with disabilities remain in a family-like environment rather than an institution; as soon as such programs are created, there should be no new admissions of children to orphanages or rehabilitation centers in Turkey; and

- Adopt an enforceable mental health law consistent with international human rights standards. This law must provide a right to independent review of any decision to detain a person in an institution.

The Government of Turkey must make a commitment to the full inclusion of people with mental disabilities in all aspects of Turkish society. This includes all people with psychiatric as well as intellectual disabilities. Fulfilling its human rights obligations toward this population will require the development of a comprehensive system of community-based mental health and social services. MDRI recommends that Turkey establish a public commission to begin immediate planning for the creation of a community-based mental health and social service system that will permit people with psychiatric and intellectual disabilities to live, work, and receive treatment in the community.

MDRI has provided detailed recommendations at the end of this report about steps that can be taken to end abuses in institutions and plan for the creation of an effective and comprehensive community-based system of mental health and social services.

Turkey’s International Legal Obligations

The government of Turkey has ratified the European Convention on Human Rights (ECHR),4 the European Convention for the Prevention of Torture (ECPT),5 the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights (ICCPR),6 the International Covenant on Economic, Social, and Cultural Rights (ICESCR),7 and the Convention on the Rights of the Child (CRC).8

Turkey is under an immediate obligation to adopt enforceable legal protections against arbitrary detention.9 As the European Court of Human Rights has made clear, the protection against arbitrary detention entails a right to independent judicial review of every detainee in a psychiatric facility.10 Individuals subject to psychiatric commitment also have a right to counsel to assist them in the commitment hearing.11

Torture, as well as inhuman and degrading treatment, is strictly prohibited by these conventions under all circumstances.12 Lack of funding does not excuse these human rights violations. In its recent summary of international human rights law, the World Health Organization stated that:

The lack of financial or professional resources is not an excuse for inhuman and degrading treatment. Governments are required to provide adequate funding for basic needs and to protect the user against suffering that can be caused by a lack of food, inadequate clothing, improper staffing at an institution, lack of facilities for basic hygiene, or inadequate provision of an environment that is respectful of individual dignity.13

The structure of Turkey’s service systems that segregate people with mental disabilities from society constitute discrimination prohibited by the ICESCR.14 The lack of community-based services violates the right to live, work, and receive treatment in the community as recognized by the UN’s Standard Rules on the Equalization of Opportunities for Persons with Disabilities (Standard Rules) and other international disability rights norms.15

Turkey’s practice of segregating children with mental disabilities from society in orphanages and rehabilitation centers is a particularly serious problem. As described further in this report, research has shown that for young children, institutions are particularly dangerous. Thus, international law now takes a strong stand against congregate care for children in institutions. Article 23(1) of the CRC recognizes that “a mentally or physically disabled child should enjoy a full and decent life, in conditions which ensure dignity, promote self-reliance and facilitate the child’s active participation in the community.”16

In addition to its obligations under the ECHR, future accession to the EU would require major changes in Turkish law and policy to bring the country’s mental health and social service system into conformity with policies established by the EU. The European Parliament of the EU has called for Member States to provide people with mental disabilities with education, community services, and opportunities for living and working in the community.17 The European Parliament has recognized that people with mental disabilities have the right to live independently and participate fully in society.18x

Preface: Goals & Methods of this Report

Behind Closed Doors: Human Rights Abuses in the Psychiatric Facilities, Orphanages and Rehabilitation Centers of Turkey describes the findings of a two-year investigation in Turkey by Mental Disability Rights International (MDRI) on the human rights of people with mental disabilities (this is a broad term that includes people with a diagnosis of mental illness and people with an intellectual disability such as mental retardation). We investigated public psychiatric facilities under the authority of the Ministry of Health as well as orphanages and rehabilitation centers under the authority of the Directorate for Social Services and Child Protection (SHCEK). The report also examines the human rights implications of health and social policies affecting people with mental disabilities in the community. This work is the product of five fact-finding investigations by inter-disciplinary teams of Turkish and US investigators that took place between September 2003 and July 2005. A short version of the report is also available from MDRI in video format at www.MDRI.org.

Behind Closed Doors assesses Turkey’s enforcement of international human rights law pertaining to people who are detained or receive treatment through the public mental health and social service system. The goal of this report is to provide the information necessary for a full public understanding and debate about matters of fundamental importance to millions of Turkish individuals with disabilities and their families. It is our hope that this assessment will assist the Turkish government and Turkish citizens in promoting the reforms necessary to bring laws and practices in the mental health and social service systems into conformity with international human rights law. The report includes detailed recommendations for reform.

MDRI has published similar reports on human rights conditions in Hungary, Mexico, Peru, Russia, Uruguay, and the United Nations administration of Kosovo. In each report, we use a framework of international human rights law to provide a fair and consistent standard of assessment.

This is the first report in which MDRI has identified a practice – the use of ECT without anesthesia – that rises to the level of torture. It is important to note, however, that this practice was used in the United States and elsewhere in the 1940s. In historical perspective, the human rights abuses documented in this report are not fundamentally different from similar problems experienced in the United States and Europe over the last fifty years. The human rights abuses we document in this report should not be tolerated in any country. Yet, unfortunately, these human rights abuses are almost inevitable in any country without strong legal protections for people with mental disabilities – providing them protections against discrimination and abuse, as well as positive rights to participate fully in society. These abuses are also inevitable in any country that, like Turkey, segregates children or adults with mental disabilities behind closed doors of institutions, be they psychiatric facilities, rehabilitation centers, or orphanages. Out of sight and out of mind, the public can forget that a significant percentage of its population will need support, assistance, and other accommodations to participate fully in society. When people are separated from society, dangerous stereotypes and stigma take hold – that people with mental disabilities are frightening, inherently bad, incapable, sick, or unable to make decisions about their lives. Placed in institutions in a position of dependence and vulnerability, these stereotypes may become self-fulfilling.

Given an opportunity to live as part of society, people with disabilities have shattered stereotypes and demonstrated that they are capable of living full and meaningful lives. In every country of the world, major changes have only taken place when users and former users of mental health and social service systems take charge of their own destiny. It is ultimately the goal of this report to encourage the government of Turkey to provide people with disabilities the opportunity to participate in determining their own future.

In the United States, Europe, Latin America, and other parts of the world, the process of mental health system reform began when the public learned about abuses in institutions and demanded change. And despite many important reforms in these countries, the abuse of this vulnerable population is an ongoing challenge everywhere. This is why strong oversight mechanisms are needed to shine the spotlight of public attention regularly and systematically on the treatment of people with mental disabilities.

This report is not intended to place blame on mental health professionals as a group. Many mental health professionals we encountered, as well as staff at institutions, work under difficult circumstances and would not continue to work except out of their professional dedication and care for the individuals they serve. It is generally our experience that, when resources are provided to improve care for people with mental disabilities, the working environment of mental health professionals and staff also improves dramatically. When legal systems create mechanisms for accountability, staff who are abusive must be removed from positions of power and authority. The result is a safer, more therapeutic, and more empowering environment for everyone. MDRI would like to thank the many public officials, mental health professionals, and staff who contributed their time and insights to our work.

A number of our sources took risks in speaking out about abuses they observed. Staff expressed fears that they could be “exiled” by having their jobs moved to remote parts of the country. Former patients who might be returned to institutions for treatment told MDRI that they were afraid of reprisals. To protect them, we have not used the names of any of our sources in this report. We have provided as much identifying information as we can to explain the perspective and basis for which a source provides information.

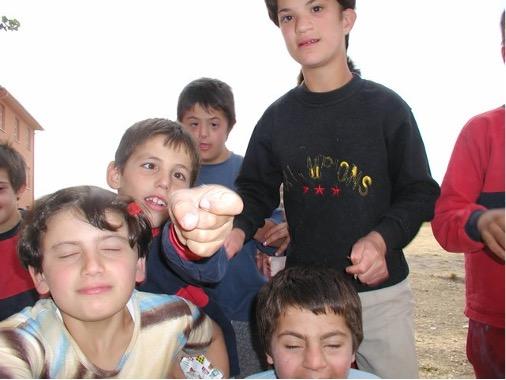

At every institution we visited, we attempted to be as thorough as we could in understanding the human rights situation of people living or receiving treatment at the facility. We asked to visit all parts of the institutions. We interviewed institutional authorities, staff, and patients. During each site visit, MDRI teams brought a video camera to record observations. To the extent that we could, we took photographs in each institution. It is our experience that photo and video documentation is tremendously helpful in corroborating our observations and helping the public to understand the reality of life in an institution. We generally find that people within institutions are amenable or eager to have their photographs taken.

We did experience some important limitations on our ability to document human rights conditions. In many institutions our access was limited. We were often prohibited from taking photographs or video. We were denied entry to a number of institutions. In many cases, institutional authorities expressed their willingness to help but stated that they did not have permission from authorities in Ankara to grant us access. On one visit to Saray, however, we were denied access despite prior approval of the visit by higher authorities at the Directorate for Social Services & Child Protection (SHCEK). This would have been a more comprehensive report if we had been granted greater access.

We are acutely aware of the limitations of understanding any society from the outside. This report is, therefore, the product of collaboration between US and Turkish citizens who have each brought valuable personal and professional experience to this project. The US citizens who participated in this investigation are all experienced in fighting against human rights abuses within the United States and in other countries of the world. It is our belief that lessons learned in other countries are of direct relevance to Turkey. Turkey can draw on these experiences – and avoid mistakes made in the United States and elsewhere. Mental health service reform has taken half a century in the United States and there is a long way to go to provide the most effective and humane services. It is our belief that Turkey can protect the rights of its citizens and bring about their full participation in society through a much quicker process of reform.

Turkey is a large country, and there are inevitably differences in the mental health and social service systems in different regions and within the sites that we visited. There are no doubt valuable programs – as well as serious abuses – that we were not able to include in our report. We acknowledge these limitations of our work. We have made every effort to provide as accurate and comprehensive an analysis of the major human rights issues as we were able to understand them. The observations and conclusions reached in this report represent the position of the authors and of MDRI alone. If any reader identifies errors or omissions in the report, we encourage you to contact MDRI at [email protected]. We intend to publish updates of this report, as well as corrections, on our website at www.MDRI.org.

This report was originally written in English. While we have made every effort to provide an accurate translation, there are inevitably differences in technical meaning or nuance. If there is any question about a discrepancy between the two versions, please refer to the English original.

I. Abuses in Psychiatric Institutions

MDRI investigators visited three large state hospitals (Bakirköy and Erenköy in Istanbul and Manisa near Izmir) as well as three university hospitals (in Ankara, Marmara, and Dokuz Eylül in Izmir). The largest psychiatric facility in the country (and perhaps the largest in Europe) is Bakirköy in Istanbul, with 2970 beds.19 At Manisa Hospital, there are 400 beds for 500 in-patients. There are at least six large state psychiatric facilities in Turkey spread out over the country (five regional facilities plus the Erenköy institution formerly dedicated to the care of state workers). There are smaller psychiatric units at university and general hospitals, as well as forensic units of prisons. In addition, the Turkish military operates psychiatric facilities that include many people undergoing evaluation of fitness for military service (we were not able to visit any of these facilities). We received varying estimates of the number of people detained in psychiatric facilities. The five regional psychiatric facilities are reported to have approximately 5,500 beds.20 In 2003, the Vice President of the Turkish Psychiatric Association reported to MDRI that there are a total of 9,000 inpatient beds in the public mental health system.

As described in Section III of this report, the mental health system of Turkey does not provide adequate services or support systems for people with mental disabilities who wish to remain living in their homes in the community. As a result, people with a psychiatric disability in need of services may have no choice but to seek treatment as an inpatient. The lack of community-based alternatives creates enormous pressures on in- patient facilities and undermines the treatment and care they can provide. By unnecessarily filling inpatient beds, there is a shortage of resources for people in need of acute care throughout the system. A small number of university hospitals are able toprovide a full range of care to the few people able to gain access to their services.

Large state facilities throughout Turkey, however, are overwhelmed. As a result, people most in need of treatment – individuals undergoing an acute psychiatric crisis – are often deprived of the attention and care they need. The assistant director of Manisa stated that, due to these pressures, no treatment other than medications and electroconvulsive therapy (ECT) is available.

A. Electroconvulsive therapy (ECT) without anesthesia

The most widespread and serious human rights violation MDRI observed in Turkey’s mental health system is the common practice of using electroconvulsive therapy (ECT) in its “unmodified” form without anesthesia, muscle relaxants, or oxygenation.

The practice of unmodified ECT creates a climate of fear that pervades public psychiatric facilities and makes many people afraid to seek any form of psychiatric treatment or care.

I only had ECT one time. It was the first and the last time. They hold you down, they hold your arms, they hold your head and they put cotton in your mouth. I heard them say 70 to 110 volts. I felt the electricity and the pain, I felt like dying. – 28-year-old former Bakirköy psychiatric patient, subjected to “unmodified” ECT

I went to Bakirköy because I was very depressed. I got medications. I had no idea what ECT was. I knew nothing except electricity was given to the brain. The doctors gave me no information. I had it nine times and I feared a lot while they were giving me ECT. They put cotton in my mouth. My eyes were opened and I saw everything. They put metal bars on both sides of my head. The moment they touched my head I saw a white light, like from a florescent light, very bright. It was very cold and I experienced a kind of pain, a different pain than I ever experienced before.

I saw someone else after they received ECT. He was trembling very much. I saw saliva on his mouth. And I thought that this cannot be a good thing whatever it is. It looked like torture. He opened his eyes wide as if he was fixed on some object. I was curious as to what it [ECT] looked like. I opened the door and saw. So finally I understood why they were hiding it. – 26 year-old former Bakirköy patient

Under any circumstances, subjecting people to extreme forms of pain and suffering constitutes “inhuman and degrading treatment” under the ECHR. TheEuropean Committee for the Prevention of Torture has ruled that the practice of unmodified ECT violates the European Convention against Torture.21 The practice of unmodified ECT in Turkish psychiatric facilities involves the intentional infliction of severe pain or fear of such pain on people who have committed no crime, are theoretically detained for their own protection and treatment, and are likely to be particularly vulnerable due to the emotional distress of their personal circumstances. At minimum, the practice of

unmodified ECT constitutes inhuman and degrading treatment in violation of the ECPT and the ECHR. To the extent that ECT is used as a form of punishment – or is held over patients as a threat of punishment – the practice rises to the level of torture under these international human rights conventions.

We use ECT for people with major depression. Patients with major depression feel that they need to be punished. If we use anesthesia the ECT won’t be as effective because they won’t feel punished. – Chief of ECT Center, Bakirköy

Electroconvulsive therapy with appropriate medical safeguards, such as anesthesia and muscle relaxants, is an accepted psychiatric treatment whereby a controlled electric current is passed through the brain to induce a seizure. Even with safeguards, ECT can have dangerous side effects, such as heart complications, prolonged seizures, apnea, and even death.22 Common side effects include headache, muscle soreness, and nausea.23 The most significant side effects are potentially severe cognitive impairments, such as amnesia and deficits in concentration and attention.24 While side effects for some people may be short term, “patients vary considerably in the extent and severity of their cognitive side effects following ECT.”25 For some people, cognitive deficits may be persistent,26 sometimes lasting years,27 and can be frightening and extremely disruptive to a person’s life.28

Despite the risks involved, mainstream mental health professionals believe that the combination of the electrical current and the ensuing seizure combine to provide short-term relief of symptoms of certain specific conditions.29 The normal course of ECT involves a series of treatments, from 6 to 21 sessions (three times a week for two to seven weeks).30 According to the American Psychiatric Association’s 2001 guidelines, the primary indications for ECT are severe major depression, acute mania, mood disorders with psychotic features, and catatonia.31 ECT may be a secondary treatment for a broader array of conditions that do not respond to other forms of treatment.32 In Europe, standards for the use of ECT are generally stricter than in the United States. The British National Institute for Clinical Excellence recommends, for example, that ECT be used “only to achieve rapid and short-term improvement of severe symptoms after an adequate trial of other treatment options has proven ineffective and/or when the condition is considered to be potentially life-threatening, in individuals with severe depressive illness, catatonia, or severe manic episodes.”33

Since the 1950s, the use of general anesthesia, muscle relaxants and oxygenation during the administration of ECT treatments has become standard medical practice.

Thus, there has been almost no research and no documentation of the dangers of unmodified ECT for almost half a century (and Turkish psychiatric facilities have never monitored these side effects). As one modern ECT researcher remembers:

When it was first introduced, electroshock was given without anesthetic, and patients approached each treatment with anxiety, dread, and panic. Some patients sustained fractures; some died. Anesthesia, muscle relaxation and hyperoxegenation were answers to the problems, but they were not accepted as routine measures until the mid-1950s, after 20 years of unmodified ECT. Unmodified treatments did harm memory, so much so that memory loss came to be seen as an essential part of the treatment.34

Much of the danger of unmodified ECT is caused by the lack of a muscle relaxant (which cannot be administered unless anesthesia is also present). ECT produces a generalized tonic-clonic seizure,35 meaning that electrical stimulation from the brain to the muscles stimulates the muscles to contract and relax repeatedly with great force.36 Such forceful contractions will put the patient at risk for any type of musculoskeletal injury, including bone fractures, joint dislocations and damage to skeletal muscle, tendons, and ligaments. In fact, it was the observation of such musculoskeletal injuries that led to the introduction of muscle relaxants to convulsive therapy in 1941.37 Prior to the use of muscle relaxants during convulsive treatment, the main risk to the patient was spinal fracture.38 In addition, several other injuries which can be greatly reduced the by administration of muscle relaxants have been reported, including hip fractures,39 hip dislocations,40 shoulder fractures, shoulder dislocations, bronchospasm,41 neck strain,42 headaches,43 and generalized muscle soreness.44

The lack of oxygenation is another danger of unmodified ECT. Professional standards for ECT include the use of oxygenation during the seizure.45 In Turkey, psychiatrists report that oxygen is available following the seizure if there an interruption in breathing, but oxygen is not usually provided during the seizure itself. Thus, there is an interruption of oxygen reaching the brain inherent in this form of unmodified ECT. Research has shown that oxygenation before, during, and after the ECT seizure reduces cognitive deficits.46

Some psychiatrists in Turkey claim that individuals subject to unmodified ECT do not feel pain because of the seizure caused by the electrical stimulus to the brain. Yet it is well established that there may be a delay of 20-40 seconds between the time electricity is administered and the time of the seizure.47 The sensation of an electric shock during this time can be extremely painful. In addition, some people may not go into a seizure at all when even after they are subject to electric shock.48 The amount of electricity required to cause a seizure varies widely from one individual to another. When anesthesia is used, it is standard practice to start with a low voltage of electricity and slowly increase (or “titrate”) the shock to use the minimum of electricity required to induce a seizure. For a person without anesthesia, this process would be extremely painful.

Given these dangers, the World Health Organization has called for the “practice of using unmodified ECT [to] be stopped.”49 The Council of Europe’s Bioethics Committee also has called for unmodified ECT to be strictly prohibited.50 In October 1997, the European Committee for the Prevention of Torture and Inhuman or Degrading Treatment or Punishment (CPT) visited Bakirköy and Samsun Hospitals and criticized their use of unmodified ECT, finding it “degrading for both the staff and patients concerned.”a

In its 1997 visit to Turkish psychiatric facilities, the use of unmodified ECT was the most serious concern raised by the CPT. The CPT called on Turkey to terminate the use of this practice immediately. The CPT also expressed alarm at the extremely high percentage of acute patients receiving ECT. The Ministry of Health of Turkey, in its response to the CPT findings, promised to support changes at Bakirköy. They stated that because Bakirköy possesses a neurosurgery department, they are prepared with both the personnel and equipment to provide anesthesia during ECT treatments. The Ministry also said they would work to ensure that the “new, state-of-the-art ECT centre,” under construction at Bakirköy and due to open in July of 1999, would perform a “leadership function for other hospitals” and would eliminate the barriers “which prevent ECT from being practiced in a modern and scientific manner.” Additionally, the Ministry reiterated that the indications for the use of ECT “are being steadily restricted worldwide” and should only be used for: (1) serious suicidal and homicidal psychotic patients; (2) psychotic patients exhibiting catatonic motor behavior; (3) psychotic patients refusing nourishment; and (4) depressive patients for whom medication remains ineffective.51

Despite a clear mandate set forth by the European Committee for the Prevention of Torture, the Council of Europe’s Bioethics Committee, and established “best practice” guidelines on the use of ECT, MDRI’s investigation finds that the practice of unmodified ECT persists unabated at Bakirköy, Erenkoy, and Manisa psychiatric facilities – and likely throughout Turkey’s public mental health system.

On MDRI’s 2005 visit to Bakirköy, investigators toured the “state-of-the-art ECT centre,” which opened in 1999. While psychiatrists at the main administration building informed us that all ECT performed at the center that day had been administered with anesthesia, the psychiatric resident who administered the ECT that day reported that no anesthesia had been used. Indeed, the resident said that ECT was only applied with anesthesia when a patient has a bone fracture or dislocated jaw. As this resident described:

We only give anesthesia to patients with bone fractures or dislocated mandibles. We gave ECT to 16 patients today without anesthesia. Patients are always nervous and afraid. Three staff is used to hold down the patient. When they give ECT on the wards, they use straightjackets. Anesthesia may lessen pre-ECT anxiety and it may be more ethical, but the patients don’t feel any pain.– Physician on duty at Bakirköy ECT center

Mental health professionals at university hospitals report that the use of unmodified ECT has been terminated because of negative experiences with its use. Many Turkish university hospital psychiatrists have taken a strong stand against unmodified ECT because of its dangers. Staff at all three university hospitals we visited reported that they discontinued the use of unmodified ECT because of the dangers they observed in patients subject to this treatment. The impact of the seizure without muscle relaxants leads to bone fractures and dislocated joints. At Manisa hospital, where unmodified ECT is still used, the assistant director reported that dislocated jaws are common. “We usually avoid [fractures] because we know how to hold the patient down,” the assistant director stated, “but when it happens, we know how to snap it back.” A psychiatrist at Ankara University Hospital described her experience with unmodified ECT before the practice was banned at her hospital, saying, “I remember one case where it cured the patient’s depression – but left the man in traction for six months when he fractured his spine.” A psychiatrist from Marmara University explained that without oxygenation, ECT can be life-threatening.

Despite these dangers, authorities at Bakirköy, Manisa, and Erenköy reported to MDRI that they all continue to administer unmodified ECT. When MDRI asked for exact numbers or information about the side effects of unmodified ECT, we learned that none of these hospitals keep track of how often dangerous complications occur. Nor were the authorities at any of these institutions aware of the Turkish government’s pronouncements to the European Committee for the Prevention of Torture about limitations on the use of ECT. At each of these facilities, authorities reported that there were no official rules or regulations, controlling standards, or guidelines on the use of ECT. Yet psychiatrists at each facility expressed that they are aware that Turkish practices are not in conformity with international medical standards.

In every professional meeting on ECT, I raise this issue. So it is still alive. I teach students here about the dangers of unmodified ECT .... Everyone knows our views. I attend most psychiatric conferences. Many other psychiatrists share our view, but they make little effort to change things. They are passive. – Professor Psychiatry, Marmara University

ECT with or without anesthesia causes short-term amnesia. According to authorities at Bakirköy, the use of ECT among young people is particularly disruptive because they often lose a full year of their education. The amnesia caused by ECT also makes it difficult to document the pain caused by its administration without anesthesia. Many people subjected to this treatment cannot remember the experience. Amnesia is not universal, however, and it was not hard for MDRI investigators to identify individuals who could remember the experience. These individuals reported feeling the electricity in their bodies and experiencing tremendous pain.

While some people feel that ECT benefits them, many others are terrified by the experience and wish to avoid it. The practice of unmodified ECT is of particular concern because it is usually administered without informed consent. Authorities at Bakirköy claim that they always obtain informed consent for ECT, and specialized informed consent forms exist at Bakirköy – yet these forms permit family members to consent on behalf of relatives (indeed, the forms provided to MDRI investigators at Bakirköy did not even have a place where the patient could sign). No legal procedure is required to empower a family member to make such a decision and no process exists to inform the patient or his or her family of the risks inherent in unmodified ECT use (see further discussion on the lack of legal protections in part IV of this report). At Bakirköy, psychiatrists report that they often have to bring patients into the ECT room in a straight jacket. At both Manisa and Erenkoy hospitals, staff report that they routinely misinform patients, telling them that they are going to get an x-ray or other medical procedure to get them into the ECT room.

During the administration of ECT, three people are used to hold down the patient. The fear of the entire patient population is magnified greatly by watching or hearing other patients subjected to ECT. At Manisa and Bakirköy, ECT is administered on the ward with other patients watching or hearing what is going on (despite the creation of an ECT center at Bakirköy, ECT is also still administered on the ward). At Manisa and Erenköy, patients reported to MDRI that they are forced to hold down others receiving ECT. One patient from Manisa reported to MDRI that he was ordered to hold down more than 200 patients for ECT:

Each time they called my name, I was terrified that it would be my turn next. I lived in constant fear of getting ECT. But holding down other patients was maybe more horrible. I was in the hospital because of my own crisis and I did not want to hurt other people. But I felt I could not say no to the staff. They could do anything to me if I said no.– Former psychiatric patient at Manisa

A psychiatrist at Marmara University explained that before unmodified ECT was abolished at his facility, he would try unsuccessfully to cover up the screams of patients. “I introduced music so other patients would not hear it. But people cried out nonetheless and there was no way to stop other patients from hearing,” he explained.

B. Over-use and misuse of ECT

With or without anesthesia, ECT is overused and misused in Turkish psychiatric facilities because of a lack of other forms of treatment. This practice exposes thousands of people to unnecessary, potentially dangerous, and frightening experiences. Turkish psychiatric facilities also use ECT in cases for which there is no evidence of its efficacy or where it is specifically contra-indicated. Under the UN’s Principles for the Protection of Persons with Mental Illness and the Improvement of Mental Health Care (the MI Principles), psychiatric care may only be provided if it is “appropriate to his or her health needs” – and not for the administrative convenience of the institution. Furthermore, “[e]very patient shall be protected from harm, including unjustified medication . . . or other acts causing mental distress or physical discomfort.”52

The use of ECT for any condition for which there is no clinically proven record of efficacy is a form of inhuman and degrading treatment and a violation of the right to health. This is true for any form of ECT – even with anesthesia and other modern medical safeguards. In addition to the known risks of ECT, there are inherent dangers to the use of any unproven medical practice. The use of an inherently risky medical procedure for unproven benefits constitutes a form of “medical experimentation” which violates article 7 of the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights.53

In 1997, the European Committee for the Prevention of Torture (CPT) expressed concern that up to 20% of the patients at Bakirköy were receiving ECT.54 During MDRI’s 2003-5 investigation, psychiatrists at Bakirköy, Erenköy, and Manisa informed MDRI that 20-33% of acute patients at hospitals receive ECT at any one time. At Dokuz Eylül University Hospital, authorities reported to MDRI in July 2005 that 40% of inpatients receive ECT at any one time.

According to the CPT, Turkish authorities claimed in 1997 that they used such a high level of ECT because of “the shortage of alternative treatment facilities.”55 During MDRI’s investigation, psychiatrists at Bakirköy and Manisa stated that ECT is frequently used because of a lack of beds in the institution and the need to move people out quickly.b At Manisa, the assistant director said that ECT is often used because the facility is chronically understaffed:

We only have a quarter of the nurses we need. ECT is supposed to be used when a patient is suicidal. But how can psychiatrists know when a patient is suicidal without enough nurses? We give ECT (unmodified) when we don’t know just to be sure.– Assistant director of Manisa

Official policy at Bakirköy is that ECT is used when medications prove ineffective. A psychiatrist at the Bakirköy admission unit explained that in practice, however, ECT is frequently used when there is a shortage of beds and there is insufficient time to assess the impact of medications. While some psychiatrists claim to use medications as the first line of treatment, they do not always leave time to assess the impact of medications. One psychiatrist at Bakirköy explained that he only waits three or four days to see if a person responds to medications before he administers ECT. “I have great experience in this, so I can usually tell in three days,” he said. This assertion is not credible. It is well established in the psychiatric literature that the effects of most psychotropic medications for major mental disorders cannot be evaluated before a patient has received them for at least 10-14 days. This is the time it takes to evaluate one medication, though most accepted treatment protocols for the use of ECT require that at least two alternatives should be tried before ECT is administered.

There is no law or professional standard in Turkey governing the practice of ECT or restricting hospitals from its misuse. In its response to the European Committee for the Prevention of Torture, however, the Turkish government claimed that ECT should be used only to treat four limited conditions. The chief psychiatrist at the Bakirköy ECT told MDRI investigators in July 2005 that “Psychiatrists make the decision about who gets ECT. We do not go by any Turkish Ministry standards.” The list of indications he provided MDRI were much broader than what was promised to the CPT. A substantially similar list was provided to MDRI independently by a psychiatric resident in charge of the ECT center when we visited in April 2005. According to them, ECT is used for:

- depression or bipolar disorder

- schizophrenia

- eating disorders, such as anorexia

- epilepsy (if anti-epilepsy medication doesn’t work)

- obsessive-compulsive disorder

- borderline patients with psychotic episodes

- people with neuroleptic malignant syndrome who cannot take neurolepticsc

- elders (because they may not tolerate medications)

- pregnant women with depression (because they cannot take all psychiatric medications)

- children 12 to 18 years of age (at least once every day at Bakirköy, occasionally on children as young as 9 years old)

- very aggressive patients

- Alzheimer’s with depression

- Parkinson’s disease

- Post-partum depression (ECT is considered the best line of treatment for this and is used before medications are tried)

- People with mental retardation with affective disorders or self-abuse

- delirium tremens due to alcoholism

- personality disorders, such as schizoid personality disorder

There is no clinical evidence of efficacy for many of these indications – such as personality disorders or substance abuse problems.56 A number of the above conditions are specifically contraindicated. The British National Institute for Clinical Excellence, for example, states that “[t]he risks associated with ECT may be enhanced during pregnancy, in older people, and in children and young people, and therefore clinicians should exercise particular caution when considering ECT treatment for these groups.”57

Widely different rationales are used to explain the rate of ECT use at different institutions. At Dokuz Eylül, a psychiatrist explained that ECT makes medications more effective. At Manisa, the assistant director explained that he is more likely to use ECT for patients who come from long distances and will not have access to medications after they leave the facility. The psychiatrist at Bakirköy said that ECT is used more and with higher voltages of electricity for black people from the southern part of Turkey.

Even when used with anesthesia, precautions are not taken that could reduce side effects of ECT. According to the American Psychiatric Association standards, “ECT treatment technique is a major determinant of the percentage of patients who develop delirium characterized by continuous disorientation.”58 The most important way to reduce cognitive side effects is to use electricity on only one side of the brain (unilateral) rather than both sides of the brain (bilateral).59 At Manisa and Bakirköy, the more dangerous form of bilateral ECT is used. In addition, large numbers of closely spaced treatments may contribute to cognitive deficits. At Bakirköy, the chief of the ECT unit said that ECT is occasionally administered intensively – up to five times a week for five or six weeks.

C. No standards of care

Psychiatrists at Marmara University Hospital state that the ongoing misuse of ECT is emblematic of a larger problem that endangers patients throughout the country’s mental health system: the lack of enforceable standards of care.

We know ECT may be used as a punishment. This is possible because you do not have standards of treatment. Medical standards would protect against abuse. – Professor of Psychiatry, Marmara University

At Manisa, the assistant director explained that the lack of standards goes far beyond the use of ECT. “There are no standards for any treatment,” this psychiatrist explained. A psychiatrist at Dokuz Eylül University Hospital in Izmir reports that in May 2005, the Turkish Psychiatric Association (TPA) adopted standards for the first time, guiding treatment for people with schizophrenia, bipolar disorder, and anxiety disorders. The standards adopted by the TPA include descriptions of the psychotherapy and psychosocial supports needed for individuals with these diagnoses. The psychiatrist pointed out, however, that it would be “impossible” to implement these standards at major psychiatric facilities such as Bakirköy because of the lack of staff available to any individual patient.

D. Custodial care without rehabilitation

The segregation of a person from society in a closed institution for a long or short period of time is enormously disruptive to a person’s life in the community. For a young person, it may disrupt his or her education, professional development, and establishment of normal social ties. For a working person, it may mean the loss of a job and the economic opportunity to care for oneself or one’s family. For a mother, father, husband or wife, placement in an institution may take a person away from family members they love and who depend on them. Research has shown that the dependency created by long- term institutionalization is particularly dangerous, leading to a decline in social and psychological functioning. Thus, it has been a trend in mental health policy for the last thirty years to move away from custodial institutionalization wherever possible. The vast majority of people with psychiatric disabilities can live in their own homes, and many can keep jobs when they are provided with mental health care and social support in the community.

Due to the enormous deprivation of liberty entailed in placement in an institution, the European Convention requires independent legal oversight in any case where a person is detained. Many people detained in institutions may not be aware of their choices or may be so distressed by their emotional condition that they cannot stand up for their rights. Thus, independent oversight of psychiatric commitment is required by international law, whether or not a person actively protests.60 In Turkey, there are no legal protections against improper detention in a psychiatric facility. Section IV of this report describes the inadequate protections against detention under Turkish law.

In addition to legal protections in the commitment process, European human rights standards require that any placement in a psychiatric facility be limited to circumstances where “placement includes a therapeutic purpose.”61 Care within an inpatient facility rather than the community can only be justified when “no less restrictive means of providing appropriate care are available.”62 If a person must be treated in an inpatient setting, he or she “should receive treatment and care provided by adequately qualified staff and based on an appropriate individually prescribed treatment plan.”63

The United Nations has adopted similar human rights principles. The UN standards state that the “treatment of every patient shall be directed towards preserving and enhancing personal autonomy.”64 The UN Special Rapporteur on the Right to Health, Paul Hunt, has recently observed that:

Decisions to isolate or segregate persons with mental disabilities, including through unnecessary institutionalization, are inherently discriminatory and contrary to the right of community integration enshrined in international standards. Segregation and isolation in itself can also entrench stigma surrounding mental disability.65

At every state psychiatric facility visited by MDRI – Bakirköy, Erenköy, and Manisa – we observed violations of these basic human rights standards. The situation is most serious for thousands of so-called “chronic” patients who are detained for life.

We also observed that many short-term acute patients are treated unnecessarily in an inpatient setting. Treatment for both groups is inadequate and frequently undermines a person’s ability to develop the psychological support and skills needed to live independently and return to the community as soon as possible. In some circumstances, particularly at Manisa hospital, we observed degrading and dangerous conditions of living.

The lack of community alternatives also leads to the inappropriate and unnecessary institutionalization of people capable of living and receiving treatment in the community. At Manisa hospital, the assistant director reported that of 500 patients at the facility, only 50 would need to be detained as in-patients if community-based services were available. At Bakirköy, more than 1,000 people remain in the institution for life.

According to psychiatrists at Bakirköy, these people are generally not violent or in need of acute care. The assistant director at Manisa says that for most people, the institution serves as a “hotel” where they stay because they have no place else to go. For these individuals, the institution provides no care that could not otherwise be provided in the community (if community-based supports were available). Yet, unlike a hotel, these people cannot leave. Having been detained so long, the assistant director of Manisa says, “most of them have lost all contact” with the outside world.

It is beyond the scope of this report to assess all the human rights concerns of inpatients in Turkish psychiatric facilities. At Manisa, we were prohibited from visiting residential wards. From four visits to Bakirköy and one visit to Erenköy, however, one major observation stands out: the near total inactivity of patients. At both facilities, people sat in beds or chairs or wandered the grounds of the facility with little to occupy them. It is widely accepted in the field of psychiatry that isolation from society combined with inactivity in an institution contributes to a decline in a person’s social and psychological functioning. A person who lives entirely dependent on an institution becomes psychologically dependent or “institutionalized.”

While our access was most limited at Manisa, our concerns at this facility were the greatest of the psychiatric facilities we visited. People wandering the grounds were generally in filthy clothing, and their hands and feet were so dirty it appeared as if they had not washed in days. Many people were missing teeth and obviously had not received dental care. A former patient said that most patients had lice in their hair and bed sheets. People at Manisa for short-term acute care are mixed together with people who have been detained for a lifetime. They are also kept on the same ward as individuals with criminal records or those who are awaiting trial for violent crimes. On occasion, children are detained on these same wards. While there are 150 women among the 500 people detained at this facility, we only saw three women outdoors during our July 2005 visit, whereas many men were freely roaming the grounds. According to the assistant director, at least 80 women are kept on a locked ward and are not allowed outside “because they cannot protect themselves from being raped.” MDRI is concerned that violence among patients or by staff goes unreported since there is no system for tracking incident reports in Manisa.

MDRI is also concerned about the denial of necessary medical treatment in psychiatric institutions (a serious problem we found in Turkey’s rehabilitation centers). We were not able to conduct a thorough investigation of this matter, but we did observe one striking case at Manisa. We observed a man at Manisa with cotton balls stuffed permanently in the remnants of his mouth and eye socket, which had been torn apart from a bullet wound. He is unable to eat except through a tube left hanging from his nose. He had attempted suicide and was told that he could not have an operation for his condition until he is released from the psychiatric facility in nine months.

At Bakirköy and at Manisa, staff psychiatrists complained about the pressures on them due to shortages of staff. MDRI is not in a position to evaluate the actual number of psychiatrists available to see patients, since we were unable to obtain precise staff to patient ratios. At Bakirköy, our team observed numerous professionals on every ward we visited. During our visits, however, we observed staff gathered at nursing stations talking amongst themselves while patients received little attention. The limited amount of time that any professional staff spends with patients is obviously a problem. The assistant Director of Manisa, as well as a psychiatrist at Bakirköy, explained that there are adequate numbers of psychiatrists, but other care givers (such as social workers or nurses) are in short supply. Despite apparently large numbers of psychiatrists on staff at Bakirköy, authorities report that psychiatrists can see patients for no more than 10 minutes at a time. Whatever the reasons for the short staff time available to patients, the result is that the public mental health system provides almost no psychosocial rehabilitation or care other than medications. Authorities at Manisa report that they only have 25% of the nurses and direct care-givers they would need for such care.

II. Abuses in Rehabilitation Centers & Orphanages

MDRI examined conditions at three so-called “rehabilitation centers” for children and adults with disabilities under the authority of SHCEK, serving a total of approximately 900 people. We visited one rehabilitation center outside of Ankara (Saray), one in Istanbul (Zeytinburnu), and one in a remote area two hours from Ankara (Ayas).66 We also visited the Kecioren orphanage for 310 children in Ankara, of whom 30 are diagnosed with mental disabilities. According to documents provided to MDRI by SHCEK authorities, there are some 18,000 children and adults in rehabilitation centers out of a total of 30,000 people in residential institutions. Our findings lead us to believe that there may be many more children and adults with disabilities in institutions than officials would indicate.d To the extent that the four institutions visited by MDRI are representative of all SHCEK facilities, we conclude that everyone detained in a SHCEK institution is at risk of serious human rights violations. For most people with mental disabilities, placement in a SHCEK facility is a life sentence that will leave them segregated from society for the rest of their lives.

My daughter is 11 years old and has a disability. I have tried to get her into six different schools, but I always get rejected. I have never worked so I can’t get the 300 million [Turkish Lire] social security I need to pay. And they say she is a difficult child. She has no toilet training and is hyperactive. But I have to think of my child’s future. Now I am a single mother and I need to work to take care of us. There should be all-day schools but now I have no options left. I don’t want to send her to Saray. A neighbor of mine told me that some children had died there because they were beaten. She told me to give her to Saray only when you know you are going to die. – Mother of a child with a disability

I love my daughter, but I hope she dies before I do. I do not know what will happen to her after I die and can’t take care of her any longer. I do not want her ever to have to live in the institution. – Mother who is also director of a private school for children with mental disabilities

A. Inhuman and degrading conditions of detention

The Council of Europe has established that “[f]acilities designed for the placement of persons with mental disorder should provide each such person…with an environment and living conditions as close as possible to those of persons of similar age, gender and culture in the community.”67 The European Committee for the Prevention of Torture (CPT) has issued standards regarding “conditions and treatment” and specifies, “inadequacies in these areas can rapidly lead to situations falling within the scope of the term ‘inhuman and degrading treatment.’ The aim should be to offer material conditions which are conducive to the treatment and welfare of patients.”68

Conditions in the SHCEK rehabilitation centers visited do not meet this standard. MDRI observed degrading physical conditions, a total lack of privacy, overcrowding, the use of physical restraints, lack of appropriate care and habilitation,e the denial of medical care, and the lack of protection against physical and sexual abuse in all SHCEK rehabilitation centers. Together, these conditions amount to inhuman and degrading treatment prohibited by the European Convention for the Prevention of Torture and Inhuman and Degrading Treatment or Punishment (the ECPT) and article 3 of the European Convention on Human Rights (ECHR). In some cases, violence in the institution, unhygienic conditions, and lack of treatment are dangerous and life- threatening. Failure to protect children and adults from dangerous conditions violates their right to life under article 2 of the ECHR.

Over prolonged periods, the inactivity and degrading conditions of living in institutions will have a major physical and psychological impact on most individuals, leading to lethargy and depression, loss of self-esteem, and a tendency not to maintain basic living or self-care skills that a person may have upon entry.69 Long-term institutionalization in degrading conditions contributes to a person’s disability. All three

SHCEK rehabilitation centers observed by MDRI were degrading and long-term detention in such a facility violates the right to the “highest attainable standard of physical and mental health.”70 Children are particularly vulnerable to the dangers of being raised in a congregate setting.71 Conditions we observed violate the Convention on the Rights of the Child (CRC), which guarantees that “a mentally or physically disabled child should enjoy a full and decent life, in conditions which ensure dignity, promote self-reliance and facilitate the child’s active participation in the community.”72

The following is an overview of observations in four institutions:

1. Saray Rehabilitation Center, Ankara

Saray is the largest state run residential rehabilitation center, officially designated for children with developmental or intellectual disabilities in Turkey. Located on the access road to the airport, on the outskirts of the city, it warehouses 750 children and adults with a variety of disabilities. With an official capacity of 408 residents at Saray, there are over 3000 children on the waiting list for admission into this already overcrowded institution. Although billed as a “rehabilitation” facility for children, it is essentially an orphanage where most people are detained indefinitely. As of September 2003, the director reported that there had been only one adoption and one foster care placement from Saray since 1988. Yet there is approximately one new admission per day.f

The population at Saray consists mainly of children and young adults between the ages of 8 and 21 years, although babies and older adults also reside there. The majority of residents are labeled as “moderately or severely retarded” and many have physical disabilities such as cerebral palsy or muscular dystrophy, and some have neurological conditions such as epilepsy.

The Saray institution consists of buildings spread out over a dusty campus separated by concrete courtyards, grassy fields, and dirt paths. Children and adults with limited or no apparent disability roam the grounds aimlessly. People are roughly separated among buildings by age, sex, and levels of disabilities. Within these buildings, people are detained in large dormitories made up of rows of beds or cribs. In most areas, there is no decoration or any place a person could keep personal possessions of any kind. Most people remain in the facility for a lifetime.

While there are some new, brightly painted buildings on the Saray campus, living conditions for residents with more severe disabilities are far worse than conditions for people with less severe disabilities. During our February 2004 visit, we observed children tied down to their beds in a barren room. When we returned in July 2004, boards had been nailed up over the windows of this room. While we could not see in, we could smell the overpowering odor of urine and feces from outside the windows.

Unable to see in through the boarded windows, I walked ahead of our guide so that I could visit the children met on my previous trip. I was able to glance into the room, where I observed a naked boy tied to a large cage-like crib. As I looked in, he tried to stand up and then he smashed his face into the metal bars. Staff wheeled out a large basket of bed sheets with an overpowering smell of excrement. The door was slammed and we were not permitted to enter. – MDRI investigator

In one ward, children and teenagers, unable to walk or feed themselves were crammed two to a crib and left to a life of near total inactivity. Without any physical therapy and confined to cribs, MDRI observed children whose arms, legs and spines had atrophied and had become twisted and contorted. Many of these children suffered from skin and eye ailments.

I observed one child who had vomited all over himself and his bed sheets left for more than half an hour covered with flies and without any help [see photo #7]. Unable to sit up or use his hands, he continued to spit up and then swallow his vomit. - MDRI investigator

There were no toys in any of the cribs or any stimuli (such as music or television) in the rooms. According to the director interviewed in September 2003, 400 of the 750 people confined to Saray “don’t do anything and are in bed all of the time.” Treating children in this way exacerbates any existing disability and can cause more serious and life threatening health problems.