INFANTICIDE AND ABUSE:

Killing and confinement of children with disabilities in Kenya

Disability Rights International

Kenyan Association for the Intellectually Handicapped

September 27, 2018

Authors:

Priscila Rodríguez, LL.M, Associate Director, Disability Rights International (DRI)

Laurie Ahern, President, DRI

John Bradshaw, JD, Human Rights Investigator, DRI Board of Directors

Arlene S. Kanter, Professor, Syracuse University College of Law

Milanoi Koiyiet, LL.M., DRI Investigator

Robert Levy, Adjunct Professor, Columbia University, Federal Judge

Melanie Reeves Miller, Disability Services Specialist

Eric Rosenthal, JD, LL.D (hon), Executive Director, DRI

Fatma Wangare, Director, Kenyan Association for the Intellectually Handicapped (KAIH)

CONTENTS

- EXECUTIVE SUMMARY

- GOALS AND METHODOLOGY

- I. INFANTICIDE AND STIGMA

- II. INSTITUTIONALIZATION OF CHILDREN IN KENYA

- III. INTERNATIONAL DONATIONS AND VOLUNTEERS ARE FUNDING ORPHANAGES

- IV. KENYA’S OBLIGATION TO GUARANTEE THE RIGHT TO COMMUNITY INTEGRATION AND TO A FAMILY

- A. Provide supports to families

- B. Fight stigma against disability in Kenya

- C. Start a deinstitutionalization process

- D. Prioritize children with disabilities and their families in all government and donor-funded programs

- E. Harmonize local legislation with right to a family and to community integration

- F. Ban international funding of institutions and orphanage voluntourism

- G. Ensure that human rights and anti-trafficking programs monitor all public and private programs for children

- H. International donors & volunteers must support reform – not perpetuate further abuse

- I. Support participation by stakeholders – including children’s rights and disability groups

- APPENDIX I. QUESTIONNAIRE APPLIED TO MOTHERS OF CHILDREN WITH DISABILITIES

- APPENDIX II. INSTITUTIONS VISITED

EXECUTIVE SUMMARY

Infanticide and Abuse: Killing and confinement of children with disabilities in Kenya is the product of a two-year investigation by Disability Rights International (DRI) into institutions and orphanages across the country. DRI visited twenty one children’s institutions – both public and private – in Kenya’s capital of Nairobi and rural and coastal communities. There were approximately 3,400 children in the facilities investigated by DRI.

Some orphanages in Kenya are registered and licensed by the government, but many facilities are unregistered and hold children without any oversight. There are an estimated 1,500 orphanages in Kenya but no reliable estimates of the number of children in those orphanages.

Basic living conditions in many of the orphanages we visited were poor, but conditions in the facilities designated for children with disabilities were far worse – dangerously so. There is almost no support for parents who wish to keep their children with disabilities at home. As this report documents, parents are placed under enormous pressure to kill their children with disabilities.

Pressure to kill children with disabilities

DRI interviewed a woman whose close friend was pressured by her family to kill her two-and-a-half year old child with cerebral palsy. After killing her child, the woman became severely depressed. Her family has rejected her because of her deteriorating mental health, not because she killed her child.

Throughout Kenya, families reported to DRI that there is a common belief that children born with a disability are “cursed, bewitched, and possessed.” Many believe it is a punishment for the sins of the mother, including being “unfaithful” to her husband. Another common belief is that if the firstborn has a disability, the baby should be killed if the parents want to have more children.

DRI conducted interviews with mothers of children with disabilities – women who had elected to keep their children, withstanding pressure from family and the community to kill their children or give up their baby.

Children with disabilities are called idiots, imbeciles, abnormal, subhuman and a burden. – Mothers of children with disabilities

With both a written survey and personal interviews, DRI questioned approximately ninety mothers who opted to keep their child with a disability.

All the women DRI spoke with said it is common for parents to be pressured to kill their babies with disabilities and “many babies are killed at birth.”

Thirty seven percent of the women surveyed from Nairobi said they were pressured to kill their children with disabilities while fifty four percent of women from the more rural areas felt pressure to kill their children. Sixty three percent of all women surveyed stated that they were told “your child is cursed.”

One mother was told to put a needle in one of her child’s veins and the needle would eventually kill them. Others were told to take their child to a witch doctor – who would either cure the child of their disability or kill them.

Medical negligence and social isolation

Many of the mothers in the survey told DRI that they left the hospitals without being told their child had a disability. Mothers complained that doctors and nurses do not want to treat them or their children with disabilities because they believe disability is dangerous or even “contagious.” Mothers are often sent home without any information or care plan as doctors feel children with disabilities are “not worth it” or are “not going to make it.”

Your child is a cabbage and will be a cabbage all her life. - Doctor to mother of child with a disability. Later she found out her child was deaf.

Most mothers in the DRI interviews, who had been pressured to kill their children, had been told that they “brought shame to their families and community” that they would be unable to afford medical expenses, or that their child “would not live a good life” as reasons they should kill them.

When women in Kenya give birth to a child with a disability they are thought to be cursed, too. According to UN authority on Violence against Children Marta Santos Pais:

Witchcraft may also be viewed as a kind of genetic inheritance, with children of accused parents or relatives also suspected of harboring evil. This leads to increased stigmatization and social isolation not only for the child, but sometimes for the whole family who must struggle under a spoiled reputation.

More than half of the mothers we interviewed felt “alone” and “sad.” Many had been shunned by their families and rejected by their husbands and in-laws. Social isolation is a way of life for mothers of children with disabilities in Kenya. Children cannot attend school and other parents will not let their children play with a child with a disability as their children “might get sick.” Many children with disabilities are hidden in their homes. Mothers told DRI than their families did not want to be associated with their children and did not allow them to return home after being rejected by husbands and in-laws. One woman shared:

My own family disowned me, they chased me away.

And still another noted:

After she was abandoned by her husband for giving birth to a deaf daughter, she was shunned by her community and could not go out with her child on her own. She stayed home for a very long time until she found Heshima – a support group for mothers of children with disabilities.

Eighty two percent of women DRI surveyed said they could not find anyone to take care of their child so that they might be able to work. Without government, charity, community or family support, it is next to impossible for mothers of children with disabilities to survive – thus reinforcing infanticide as an option.

Institutions and orphanages in Kenya

In the 21 institutions DRI visited, there were approximately 3,400 children – some as young as one week old. In the coastal city of Mombasa we found another 3,000 institutionalized children. Given that there are an estimated 1,500 orphanages in the country, the total number of children in Kenya’s orphanages is likely to be vast.

Most children in orphanages are not orphans – it is poverty and disability that push children into orphanages. For the most part, children are not abandoned due to abuse, but rather because their families do not have the resources to adequately care for them.

The situation in institutions for children with disabilities is dire – DRI found children with disabilities in overcrowded and filthy conditions, children spending lengthy time in restraints and isolation rooms, overall lack of staff and untrained staff, neglect, and the withholding of medical care – treatment is readily available, yet children with disabilities are intentionally left to die. Children with disabilities – if they survive childhood – will likely spend their adult lives in institutions – death will be the only way out.

Although children with disabilities are at serious risk of abuse in institutions, all children locked away and forgotten are likely to be emotionally, physically and/or sexually abused. DRI has documented severe neglect, physical and sexual abuse, and torture in Kenya.

DRI found children in institutions locked overnight for thirteen hours or more, their lives at risk if there were to be a fire. In many places space was so scarce that four or more children shared one twin bed.

The light bulb was coated with dead bugs and dirt and was a potential fire hazard. The program director reported that the children are locked in the room at approximately 6pm each night and the door is not open until sometimes 7am the next morning. The door to the room was of solid steel with a latch bolt. If there were a fire, the children would perish before assistance could be provided. – DRI investigator

The list of egregious human rights violations perpetrated against children seems without end. At Compassionate Hands for the Disabled, children with cerebral palsy were left to feed themselves even though they were tied to chairs and were unable to hold spoons. For eighty-seven children, there were four staff members (some of whom were barely teenagers) and two volunteers.

At the Dagoretti Rehabilitation Centre five hundred children were crammed into several filthy rooms and passageways. An older child was guarding the door with a machete and a whip – to prevent children from leaving. Rehabilitating drug addicts and former male prisoners were roaming the facility with teenage boys and girls.

At Baby Blessing Children’s Home, DRI found thirty six babies crammed into two small rooms with few staff. At Christ Chapel Children’s Home, the director told DRI that “children make mistakes.” They are punished by being locked in a dark room with no windows. They remain there for a whole day and are not allowed to play and are given no food. According to the Director, “the children are terrified of the room and none of them wants to be there.”

International donors, volunteers and mission trips fueling the orphanage business and trafficking of children

DRI interviewed a Kenyan government official from the Ministry of Labor and Social Protection who said that “trafficking is very high” in institutions; “children are being recruited and they’re shipped out of the country with promises of better lives but they go and they end up in brothels where they are sexually exploited.” This official mentioned that the Children Services Department is working with the Criminal Investigation Department to focus on orphanages “where children are being exploited.” The exploitation is in many cases being carried out by ‘foreigners.’ According to the official, “foreigners are paying to come, they are paying school fees for children and are sexually exploiting them.”

In many developing countries, it has been observed that orphanages have become a booming business. And children are the commodity (see e.g. Laurie Ahern, Orphanages are No Place for Children, The Washington Post, August 11, 2013). Orphanages have also been recognized as feeders for child trafficking (Laurie Ahern, Huffington Post, January 2, 2016).

Most children in orphanages are not orphans. They have living parents and extended families. Poverty and the belief by families that their children will be better off in institutions – that they will be well-fed, given an education, or have access to rehabilitation for a child with a disability - drive them to give up their children.

By supporting orphanages rather than parents – many of whom are desperate to keep their children – donations are effectively splitting families apart and leaving children exposed to neglect, abuse, and trafficking. In Kenya, DRI found orphanages supported by thousands of dollars through mission trips and volunteers. Yet at the same facilities children are still living in squalor, or worse. Orphanage owners convince poor families they will take good care of their children while volunteers and mission groups – who most often undergo no background checks – have unfettered access to children and pay or donate thousands to volunteer at an orphanage.

Orphanages realized that if they had more children they could get more donations. At first, they only had local donations but now they started getting international donations. As they received more money, they realized they could use it for themselves…orphanages are not good places. They receive donations from people and misuse the resource, buying the most expensive cars for themselves while the children remain isolated from their families. – The local chief of Murango County on the outskirts of Nairobi

Happy Life Children’s Home asks for 50 USD per month to sponsor a child. According to the Director, 35 children are being sponsored thus far. Yet there are only two, non-professional staff for sixty children.

A Canadian website, Lift the Children, raises funds for up to one hundred orphanages in Kenya and many more around the world. Some of the most abusive orphanages uncovered by DRI – Dagoretti Rehabilitation Centre and Agape Home – are listed on their website as receiving funding.

According to the 2018 US State Department Trafficking in Persons (TIP) report:

Profits made through volunteer paid program fees or donations to orphanages from tourists incentivize nefarious orphanage owners to increase revenue by expanding child recruitment operations in order to open more facilities. These facilitate child trafficking rings by using false promises to recruit children and exploit them to profit from donations.

The volunteers themselves also represent a risk to the emotional wellbeing of the children. Volunteers that come and go constantly create and break emotional bonds with the children, which leads to attachment disorders in the children.

The Trafficking in Persons report also found that “volunteering in these facilities for short periods of time without appropriate training can cause further emotional stress and even a sense of abandonment for already vulnerable children with attachment issues affected by temporary and irregular experiences of safe relationships.”

Recommendations

All human beings are born free and equal in dignity and rights. – Universal Declaration of Human Rights (1948)

Kenya must take immediate action to stop the killing, torture and abuse of children with disabilities. It is fundamental to the obligations of all nations under international law that human life must be protected – for children with and without disabilities. Kenya has ratified the UN Convention on the Rights of the Child (CRC) and the UN Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities (CRPD) – which require governments to take action necessary to prohibit and prevent the killing of children and protect the right of all children to live and grow up with a family.

The CRPD requires States to:

…adopt immediate, effective, and appropriate measures to raise awareness throughout society, including at the family level, regarding persons with disabilities, and to foster respect for the rights and dignity of persons with disabilities. – CRPD, Article 8

It is the government’s obligation under international law to enforce existing criminal laws against infanticide. Kenya must educate the public, communities, health care professionals, and traditional carers about disability and should provide families the support they need to ensure children with disabilities grow up in safety.

Many of the practices of infanticide in Kenya are based on deeply rooted stigma and cultural traditions. Stakeholders and communities should be engaged in developing solutions to stop infanticide and institutionalization that will be appropriate and effective in Kenya. People with disabilities and family members are key constituency groups that must be engaged in creating solutions.

The CRPD requires governments to “consult with and actively involve persons with disabilities, including children with disabilities, through their representative organizations…concerning issues relating to persons with disabilities.” Organizations like Child in Family Focus Kenya have been at the forefront of a deinstitutionalization movement seeking to shift the supports to family based alternatives. The Kenyan Association for the Intellectually Handicapped (KAIH) has shined a light on the challenges for children with intellectual disabilities in Kenya and the need to create supports for them and their families. It is crucial that the government engages in discussions with these relevant actors for meaningful reform.

Kenya must create support programs for at-risk families so that no child is placed in an orphanage or institution of any kind. All children with and without a disability need the love and care of a family. Extensive research now shows that placing any child in an institution (or residential program of any size) of can cause psychological damage and leads to increased developmental disabilities. In addition, placing children in institutions exposes them to increased risk of violence, trafficking, and torture. Given the dangers of placing children in institutions, UNICEF’s 2013 State of the World Children Report called for an “end to the institutionalization” of children.

The United Nations Office of the High Commissioner for Human Rights (OHCHR) has observed that:

Institutional care in early childhood has such harmful effects that it should be considered a form of violence against young children…

Based on these findings, and “in accordance with international human rights and good practice norms,” OHCHR calls on all states to:

… place a moratorium on new admissions of children with disabilities into institutions [and] seek alternative family placement rather than any form of residential care for children who must be removed from their own family… – UN OHCHR, U.N. Doc. A/HRC/34/32, para. 58 (Jan. 31, 2017), para.58

Kenya is responsible for ensuring that international donations and volunteers do not perpetuate the segregation or abuse of children. Kenya should prohibit international volunteering and funding for orphanages and redirect such assistance for the protection of families and the full community inclusion of children with disabilities. As described in this report, there are many worthy non-governmental initiatives in Kenya to support children living in the community and to protect the rights of children with disabilities.

Reform programs to close institutions and support family reintegration should prioritize – and never exclude – children with disabilities. Kenya must establish effective human rights oversight and enforcement systems to protect children with and without disabilities. There must be an immediate accounting for all children now confined to institutions.

GOALS AND METHODOLOGY

Between 2016 and 2018 DRI conducted four fact-finding trips to Kenya and visited institutions in Nairobi, the capital; Muranga County and Kitui, two counties near Nairobi; and Mombasa, a major city on the coast. The original aim of our investigation was to document the situation of children with and without disabilities in institutions and to examine the pressures on families to give up their children. Based on our initial findings, we expanded our investigation to examine the problem of infanticide of children with disabilities. DRI visited 21 institutions – 17 private and 3 public. The institutions visited are listed in the Appendix II. For a visit in November 2017, DRI was accompanied by Melanie Reeves Miller, a Disability Services Specialist who has served as an expert monitor to assess institutions and social service systems in the United States. In June 2017, Professor Arlene Kanter accompanied DRI staff on their visits to orphanages.

From 2017 to 2018, DRI conducted a quantitative and qualitative study on the challenges that mothers of children with disabilities face in Kenya. The quantitative study consisted of a structured survey conducted by DRI with the support of Kenyan Association for the Intellectually Handicapped (KAIH), one of the leading disability organizations in Kenya at the forefront of protecting the rights of children with disabilities and fighting the stigma and discrimination they face. DRI surveyed 61 mothers of children with disabilities for the quantitative portion of the study. The survey asked six questions regarding motherhood and disability, maternity care and supports and it is available in Appendix II at the end of this report. Of the women included in the DRI’s study, 24 lived in two counties outside of the capital – 11 in Narok, and 13 in Nakuru.

In addition, DRI conducted in-depth interviews with 30 parents –mostly mothers – of children with disabilities on their experiences with disability and stigma in Kenya. Seven of these parents attended a workshop organized by DRI and KAIH. The workshop was centered on the right of children with disabilities to supports and services in the community. DRI interviewed 11 mothers of children with disabilities that work for the organization Heshima, an organization that provides education opportunities for children with disabilities and employment opportunities for their mothers. Lastly, DRI interviewed 12 parents of children with disabilities that are part of the Jomvu Constituency Disability Network for Persons with Disabilities (JOMVU Network) in Mombasa.

DRI thanks Gerardo Martínez y Carriles, who accompanied the first investigation, and Ricardo Martínez Mina, who carried out the initial research to identify institutions for children with and without disabilities in Kenya.

I. INFANTICIDE AND STIGMA

Throughout our investigation, parents of children with disabilities told DRI that their children are stigmatized and accused of being cursed or bewitched. DRI’s study shows that parents, especially mothers, are often pressured to kill their babies or “give them up.” Among the mothers surveyed, 45% said that they had been pressured to give up and or kill their child. Mothers who kept their children were pressured to leave their children in an institution. DRI’s investigation into the situation in orphanages found that children in institutions are at risk of suffering inhumane and degrading treatment and torture. Some conditions within facilities we observed were immediately life threatening (see Part II of this report).

Lack of adequate medical care and supports for parents of children with disabilities adds to the stigma and the pressure to “give up” a child with a disability. Mothers spoke of an utter lack of information from health professionals on the disability of their child as well as a lack of adequate post-partum care. Parents of children with disabilities, especially mothers, told us that they do not receive adequate supports from the government to take care of their children. Mothers who refused to give up their children expressed sadness and feelings of loneliness as they are often ostracized from their families and communities due to the disability of their child.

A. Pressure to kill a child with a disability

DRI interviewed a woman whose close friend was pressured by her family to kill her 2 1/2 year old child with cerebral palsy. After killing the baby, the woman became severely depressed. The family has rejected her because of her deteriorating mental health, not because she killed her baby.

Parents who participated in a workshop organized by DRI and KAIH said that there is a belief that children with disabilities in Kenya are “cursed, bewitched and possessed.”[1] According to their parents, children with disabilities are perceived as “idiots, imbeciles, abnormal, subhuman, a burden.”[2] They are further believed to be a punishment to the parents, especially mothers, for their sins. Mama Anna (*not her real name) was accused by her community of trying to get an abortion, perceived as a sin in Kenya, which resulted in her child’s disability. Mama Anna’s husband told her that she had used witchcraft which caused her child’s disability; her parents in law blamed her for the disability of the child and sent her back to her family. A woman who was surveyed wrote that her family claimed that she had been unfaithful to her husband “and that is why I have a child with disability.”

Given the negative beliefs that surround children with disabilities in Kenya, all of the parents interviewed by DRI stated that it was a common experience for parents with disabilities in Kenya to be pressured to “give up” or “to kill” their baby. As a result, “many children are killed at birth.”[3] Other groups have documented the killing of children with disabilities by being abandoned in the woods to die, deliberately starved to death, or buried alive in Kenya and East Africa.[4]

Among mothers who participated in the structured survey, 45% said that they had been personally pressured to kill their child. One mother was told to put a needle in one of the veins of her child, and that the needle would eventually kill it. According to the mothers, stigma and pressure to give up their child is worse in rural areas.[5] DRI’s study finds that the percentage of women who were pressured to give up their children is higher in rural areas than in the city. In Nairobi, 37% of the surveyed women responded that they had been pressured to kill their child while in rural areas, 57% of mothers reported pressure to kill their child.

Almost two thirds of the women (63%) stated that the reason why they were told to kill their child was because “the child was cursed.” These findings are consistent with a problem identified by the Special Representative of the UN Secretary General (SRSG) on Violence against Children, Marta Santos Pais, who has observed that “orphans, children with disabilities, children with albinism, prematurely born or ‘bad-birth’ children, specially gifted children or those who are simply deemed “different” are most often targeted and branded as being witches.”[6] According to Santos Pais, being accused of witchcraft or of being cursed is “often associated with other forms of violence, including serious abuse tantamount to torture, sometimes leading to life-long injuries and even death.”[7] In DRI’s survey, 25% of the women who pressured to kill their child were told to take the child to a “witch doctor” who could either “kill or cure the child.”

Other cultural beliefs on disability also threaten the lives of children born with a disability in Kenya. In Mombasa, DRI interviewed the chairman of local organization Community United for the Advocacy of the Child. According to him, in the community there is a common belief that if the firstborn child has a disability, he should be killed if the parents want to have more children. In 2017, there was a case of a mother who gave birth to a blind child and who had to run away because the father of the child was trying to kill him. Community United for the Advocacy of the Child helped the mother find a place to live temporarily. The father found the mother and her son but before he could harm them, he was arrested.

Among women pressured to kill their baby, 54% told DRI that the reason given to them was that they “had brought shame to their family and community” for having a child with a disability. A third of the women were told to kill their child because they were not going to be able to afford the medical expenses. Fifteen percent of the women were told that they were not going to be able to work and take care of their child while eleven percent were told that their child “would not live a full life,” so there was “no point in keeping the child alive.”

Two thirds of the women who answered that they had been pressured to kill their child stated that they had been pressured by a family member, either their husband (14%), their own family (37%) or their husband’s family (26%). The remaining third of the women were told to give up their baby by someone in their community, their church, or by their friends.

It is hard to know how many women actually agree to kill or “give up” their babies in Kenya. All of the women we interviewed had kept their babies but a few of them shared that they knew other women who had not. All of the mothers we interviewed were part of support groups that may have helped them keep their children. This includes Heshima, the JOMVU Network (Mombasa), and the Kenyan Association for the Intellectually Handicapped (KAIH). One of the mothers from Heshima told us that she was close to “giving up” before she found Heshima and was given a “life opportunity” when she was employed by the organization and her child was accepted to attend the school. Had she not found Heshima, she stated that she may have given up her baby, like many other women who are unable to access supports.

B. Social isolation of the child with a disability and the mother

In Kenya, a woman’s identity is heavily linked to motherhood. From the moment a woman gives birth, she will be known as “Mama” followed by the first name of her first son or daughter. According to some of the mothers DRI interviewed in Heshima, when a woman gives birth to a child with a disability, she is thought to be cursed too, like her child. The UN SRSG on Violence against Children has found that:

“Witchcraft may also be viewed as a kind of genetic inheritance, with children of accused parents or relatives also suspected of harboring evil. This leads to increased stigmatization and social isolation not only for the child, but sometimes for the whole family who must struggle under a spoiled reputation.”[8]

Social isolation is a reality for mothers who keep their children with disabilities in Kenya. Over half of the surveyed women responded that they feel alone (54%) and sad (51%). A great majority (72%), stated that their families and/or their communities rejected them and their children with disabilities. One in five women said that the father of their child abandoned them after he found out the child had a disability.

One of the mothers from Heshima told DRI that, “there is a lot of stigma against children with disabilities; the community will ostracize you and your child.”[9] Mothers from Heshima told how their own families did not want to be associated with the child with a disability and did not allow them to return home after being rejected and sent away by their husband and in-laws. One woman shared that “my own family disowned me, they chased me away.” Mama Paul (*not her real name) noted how, after she was abandoned by her husband for giving birth to a deaf daughter, she was shunned by her community and could not go out with her child or on her own. She stayed at home for a very long time, until she found Heshima, a place where she and her daughter were treated with dignity. Mama Anna told DRI: “I locked myself and my baby in the house for a long time because of all the negative talk about my son.” Another surveyed mother stated: “I can’t take my child to church since they have not accepted my child.”

Stigma affects all areas in the life of a mother and child, including work and school. One surveyed woman wrote: “I have a hair salon business and some clients refuse to come when they see I have a child with a disability.” Children with disabilities also face rejection from schools. One of the mothers from Heshima told DRI: “I was told that my son should go to school, but after three months they told me that my son had brought disgrace to the school. I took my son back home and I cried.”

Two surveyed mothers shared that their children were rejected from schools because they of their disability. This is in part because disability is thought to be contagious. Mama Paul from Heshima recalled how some parents refused to let their children play with Steve, saying they will also get sick. The director of Heshima told us that they started a water project to employ the mothers of children with disabilities and provide clean water to the community through the installation of a well. At first however, the community did not want to get water from that well because it was operated by mothers of children with disabilities and they thought they could get “infected.”

Given the strong stigma that parents with disabilities face in the community and the rejection children with disabilities face in schools, many children with disabilities are left hidden at homes. According to the parents interviewed by DRI, “children with disabilities are still being hidden in homes because of community attitudes and stigma.”[10] The Action Foundation works with children who are hidden at home and with their parents; it trains the parents and rehabilitates and reintegrates the children to schools. In June 2017 DRI visited the Action Foundation and met a three-year-old girl who had been rehabilitated by them. According to the Action Foundation, when they met her she was severely malnourished and had reportedly never left her home, her muscles had atrophied, and she had barely grown.

C. Medical negligence and lack of information for parents of children with disabilities

Mothers interviewed by DRI stated that nursing staff and doctors, particularly at public hospitals, do not tell the mother of the child that the child has a disability when they are born. The mother and child are often sent home without any information or care plan. According to Mama Paul from Heshima, “the doctors and nurses at the government facility where I gave birth never informed me that my son had a disability. They just sent me home with no explanation at all.” Another mother from Heshima shared how she gave birth after two weeks of labor, and her son “was tired and could not cry.” He was put in a nursery for one month. After that, she was told to take her child home but was not told that her child had a disability. Once at home, “I realized that my child was weak, could not breastfeed and eventually did not sit or walk.” Another mother from Heshima told DRI: “my baby was born with a disability, but I was not told when the baby was born. They did not feel that my child was worth enough to tell me what her condition was and how I could take care of her.”

It can be months and even years before a mother finds out that her child has a disability, which may deprive the child of critical healthcare that could mean the difference between death and survival. Of the surveyed mothers, 93% stated that they found out that their child had a disability only after they took the baby home. A quarter of the women found out within the first six months, a fifth within a year, a third within 3 years, ten percent within six years and 3 mothers found out their child had a disability up to 15 years later. Most of the women realized on their own that their child may have a disability. Two thirds of the surveyed mothers responded that they suspected their child may have a disability because they were not reaching certain milestones, such as sitting up, crawling, talking or walking. A total of 18% found out when they took their child back to the hospital because they became ill. Only four mothers out of sixty-one said they had been informed that their child had a disability when they were born.

Once the mothers realize that their child may have a disability, they still face a lack of information, guidance, and treatment from doctors, particularly in government hospitals. As a result, half of the surveyed women responded that they did not know how to best take care of their child. According to a mother from Heshima, “doctors do not give you all the information about the child and his diagnosis. They assume you will not understand and do not try to explain anything. I went to several government clinics and nobody told me about the condition of my daughter. I had to go to a private doctor to get the information.” A mother interviewed by DRI stated that “doctors assume that the parents do not understand, therefore they don’t even care to explain. They just give you medication and tell you to give it to the child and nothing else.”

One of the mothers currently working at Heshima said that parents seeking services for their children with disabilities in public hospitals face a lot of stigma. Her daughter has cerebral palsy, but she did not know the diagnosis for several years. She went to various public hospitals, but no doctor informed her of her child’s disability. She was just given medication with no explanation of what it is for. Another mother from Heshima stated that “there is no assistance from government hospitals and we did not know where to go get help for our children as this information is not available. The system is also so corrupt and therefore not easy to get help.” A mother that participated in DRI and KAIH’s workshop stated that “the doctors are very dismissive to parents of children with disabilities especially government facilities.”

The mothers also reported many instances of serious medical negligence. One mother from Heshima said that “I noticed that my child was not well because he was convulsing a lot. I went to the doctor and he just gave me medication. He did not explain to me what it was for. When the medication was over, my child started convulsing again. The doctor did not care to tell me that I needed to come and get more medication when I ran out of it.” Another mother similarly stated that “I gave birth at Kenyatta National Hospital (KNH) and my child was convulsing. They gave him medication while in hospital, but they never informed me the diagnosis or that I needed to give him the medication every day. When I was discharged from hospital, they never told me that my son should continue taking the medication. We went home, and he continued convulsing.”

Mothers that were interviewed stated that most government facilities have nurses “who do not understand disability rights, they are rude to parents of children with disabilities and even in offering services they do not explain to the parent what needs to be done.”[11] According to a nurse that works at Kenyatta National Hospital and who attended the workshop organized by DRI and KAIH, nurses and doctors do not want to treat children with disabilities because of the stigma surrounding them; “many nurses believe that the disability could be contagious and do not want to treat the child.” According to this nurse, doctors also believe children with disabilities are not “worth it” or “are not going to make it.” Mama Anna from Heshima said that after she realized something was not right with her daughter and sought medical attention, the doctor told her that her child was “a cabbage and would be a cabbage all her life.” She later found out that her daughter was deaf.

According to Joseph (*not his real name), a father of a child with a disability, the utter lack of information available to parents makes it harder for them to fight stigma and, in the end, to decide to keep their child.[12] Joseph talked about how complications during the birth of his son resulted in a disability. Nobody explained to him what had happened to his child, but he knew it was not his wife’s fault. If anything, he believed it was the fault of the nurses that were delivering his baby. When his and his wife’s families attacked his wife (the mother of the child) for having a disability and accused them of being cursed, Joseph said he could stand up to them because he knew for a fact that his child was not cursed. Without that certainty, “it would have been hard to fight the stigma and everyone telling you your child must be cursed.” Joseph is calling on hospitals to provide more information to families, as information is the best tool parents have to fight the stigma that they and their children will face on a day to day basis.

D. Lack of supports to families

Parents who keep their children reported to DRI that there are not adequate supports, including financial support, accessible schools, or job opportunities. Almost two thirds of the surveyed women responded that one of the main struggles they faced is the lack of support. Parents interviewed by DRI stated that they face hardships and an uphill battle to get their children education and the chance of a better life. Mothers of children with disabilities that belong to JOMVU Network reported to DRI that they have to carry their children on their backs to bring them to the only public school that accepts children with disabilities in the county. The roads are inaccessible, some children do not have wheelchairs, and there is no school bus to pick up the children.

Two surveyed women wrote that “I have to take my child to school carrying him on my back” and “the roads are inaccessible, and it is hard to move a wheelchair, so I have to carry my child on my back everywhere including to and from school.” According to one surveyed mother, “the school is inaccessible, and it makes my child's life difficult.” A teacher from one of the few public schools in Mombasa that accepts children with disabilities stated that due to the lack of accessibility, children with more severe disabilities just stay home.[13]

Among mothers surveyed, 97% responded that one of the main struggles they face is that it is very expensive to raise a child with a disability. Parents interviewed by DRI agreed that taking care of a child with disability is expensive in Kenya. According to parents from the JOMVU Network, “taking care of a child with disability is expensive with regards to food, medication and diapers. Some have severe disabilities and they use adult diapers.” Some of the families receive Ksh. 2,000 (USD 20) per month as support from the government. However, according to a mother whose child has spina bifida, she spends Ksh. 8, 160 (USD 81) per month on diapers alone. All of them have other children and struggle to make ends meet.

Over half of the surveyed women stated that they cannot find work as a mother of a child with a disability. Eighty two percent responded that they could not find anyone to take care of their child if they went to work. Some of these mothers face extreme hardship, as shown by the story of Mama George, one of the surveyed mothers. She was abandoned by her husband and shunned by her family and her community after she gave birth to a child with cerebral palsy. She has not been able to find a stable job that will allow her to bring her child with her or find someone to take care of her child while she goes to work. To survive she works plots of land for a day. She carries her child with her but the child cannot stand or sit on his own, so she digs a hole in the ground where she can “sit” him while she works. When she is done for the day she picks him up and carries him back home. She worries for the time when her son will be too big for her to carry, and she will not be able to take him with her to work.

II. INSTITUTIONALIZATION OF CHILDREN IN KENYA

Throughout the world, a large percentage of children in orphanages have at least one living parent or extended families.[14] This is certainly true in Kenya. DRI found that children in institutions in Kenya are placed outside the family because the families are unable to care for them due to poverty, disability, and lack of supports, or a combination of these factors. Given the stigma and pressure to kill children with disabilities, support and information for families is especially important to avoid unnecessary institutionalization. Despite the obvious dangers that exist for children in the community, DRI’s investigation demonstrates that placement in institutions may be even more dangerous.

A. Poverty and disability: major factors behind institutionalization

“If I had had the resources, I would have kept my grandson with me.”

– Grandmother of a child who was in an institution.

“Some are in contact with their family, but they are poor, therefore they stay here.” – Director, Christ Chapel Children’s Home

More than half of the institutions that DRI visited informed us that “most” of the children have parents.[15] According to a social worker in Nyumbani Village “all of the children have at least extended families.” Several children in the institutions “go home during the holidays,” as reported by the Local Chief of Muranga County and by a number of institutions.[16] Based on interviews carried out by DRI, we found that children are in institutions not because they do not have any family, but because their family (nuclear or extended) does not have the resources to adequately care for them; there is a presence of disability in the family – the parent, the child, or both; or, the child simply got lost and authorities have been unable to locate the family.[17]

The lack of support for parents living in poverty is an important factor behind the institutionalization of children.[18] The majority of institutions explained that most of the children placed in their facilities are unable to live with their parents because they are financially unable to care for them. Despite this, the great majority of institutions do not try to reach out and support children to remain with their families. Only two institutions visited by DRI, Dream Children’s Home and Nyumbani Village, carried out efforts to locate the children’s families. Dream Children’s Home has 87 children and they had located the families of 83 -95% of their population.[19] According to the Director, the children remained in the institution because the families did not have the resources to care for them. Similarly, a social worker in Nyumbani Village stated that they are always able to track down the extended families of the children. Once they are identified, Nyumbani Village informs the family that their child is at the institution. However, the child is not sent back to his or her family. According to the social worker, “most extended families are too poor to take care of the children.”[20]

Children of single mothers and teenage mothers are also at risk of ending up in an institution. Five institutions – a quarter of the institutions visited – reported that several children at their institution were given up by single mothers.[21] In one institution, New Hope Children’s Center, the Director told DRI investigators that more than half of the children were from single mothers. In another institution, Happy Life Children’s Home, the Director told us that they received several children from teenage girls who would not or could not keep their children. In this institution DRI found one child that was one week old who had just been given up by his teenage mother.

Disability is also a major factor behind institutionalization. Many parents of children with disabilities must cope with poverty and with the stigma of having a child with a disability. According to the Chief Program Officer of the National Council for People with Disabilities (NCPWD) “many of the children with disabilities that are in institutions have a family.”[22] However, according to the Director of the National Children’s Department, “culture still plays a role as having a child with a disability is said to be taboo and there are also financial constraints for most families. Unable to take care of their children, some parents place the children in institutions.”[23]

Lack of information, supports and services for families of children with disabilities – discussed in the first part of this report – plays a role in their abandonment and institutionalization. The Chief of Muranga County stated that “it is hard for the families of children with disabilities, the mother cannot work or take care of the home. They need support.”[24] The Director of the Association of Charitable Children’s Institutions (ACCIK) stated that “there are no supports for children with disabilities and their families, so they are likely to end up in an institution. Children are locked up like animals.” In Maji Mazuri, a private institution for children with disabilities, we were informed that the majority of the children had families, but they were too poor or unable to take care of them. In another institution, Compassionate Hands for the Disabled, DRI found 89 children with disabilities including autism, cerebral palsy and intellectual disabilities. Most of these children had families but, according to one of the staff, they were too poor and unable to care for their children “so they leave them at the institution.”[25]

The Head of the Children’s Department recognized that public institutions to which abandoned children with disabilities are sent “lack facilities and specialization to provide for their care.”[26] DRI found that private institutions where children with disabilities are sent are also extremely abusive. At both Maji Mazuri and Compassionate Hands for the Disabled we found severe overcrowding, unhygienic conditions, use of prolonged restraints and isolation rooms, lack of staff, neglect, feeding practices that put the children’s life at risk, and inadequate medical care.[27] Lack of supports for families of children with disabilities condemned them to a life of institutionalization and abuse in these institutions.

Mothers with disabilities are also likely to have their children taken away from them and put in an institution. According to the Director of New Hope Children’s Center, one of the girls has a mother “who is dumb”, that is, she has an intellectual disability. “The girl stayed with her mother in a village. A pastor that went to preach to that village could not leave the girl with her mom because she was dumb, so he brought the girl here.”[28] Separation of children based on the presence of a disability in the parent, the child, or both is further in violation of Article 23 (right to a family) of the Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities, as discussed in Section IV.A.

- Indefinite segregation of children with disabilities

Placement in an institution is especially dangerous for children with disabilities, because they usually remain in institutions after they have become adults. The Director of a public institution, Thika Rescue Center, stated that children with disabilities were likely to stay there indefinitely or be transferred to another institution.[29] In Nyumbani Village, DRI found 8 children with disabilities, most of whom have siblings also in the institution. A social worker stated that when the siblings turn 18, they will leave the institution but the children with disabilities will stay indefinitely because “they have nowhere else to go.”[30] DRI found a young man, presumed to be around 30 years old, still at this institution.

Maji Mazuri said in relation to children with disabilities that “the government has nowhere to take them and they tell us to stay with them.” This institution houses a 36 year old man with a disability. According to staff, he had “outgrown the institution” so they are planning to take him to Mathare Psychiatric Hospital, the only psychiatric institution for adults with disabilities in Kenya. This report is focused on children in institutions but DRI did visit the Mathare Psychiatric Hospital. This facility is a very large facility where we observed unhygienic and degrading conditions. Many people are left to languish on the floors and patios without any meaningful activity or prospect of reintegration into the community.

Article 14 (right to personal liberty), paragraph 1 (b) of the Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities (CRPD) unambiguously states that “the existence of a disability shall in no case justify a deprivation of liberty.”[31] Segregation of children based on their disability constitutes arbitrary detention and violates Article 14 of the CRPD.

B. Lack of oversight and monitoring

According UN former Special Rapporteur on Torture Juan Méndez, “the detention of children is inextricably linked […] with the ill-treatment of children, owing to the particularly vulnerable situation in which they have been placed that exposes them to numerous types of risk.”[32] Mr. Méndez stated that “the particular vulnerability of children imposes a heightened obligation of due diligence on States to take additional measures to ensure their human rights to life, health, dignity and physical and mental integrity.”[33] Article 16 of the CRPD requires States to monitor and supervise institutions where children with disabilities and adults are detained.[34] The lack of oversight and rights protection leaves children especially at-risk of abuse.

It is difficult to evaluate the total number of children in institutions as no reliable data is available from government authorities, and there is a lack of oversight and monitoring. In its recent evaluation of Kenya, the Committee on the Rights of the Child (CRC Committee) simply observed that “a large number of children are living in care institutions.”[35] The Association of Charitable Children’s Institutions (ACCIK) estimates that there are over 1,500 private institutions in Kenya. According to the CRC Committee, most of the institutions in Kenya are not registered, so there could be many more.[36] In addition to the private institutions, there are twenty eight government institutions for children who are in conflict with the law or in “need of care and protection” – children who have been lost, abandoned or abused.[37]

In the institutions visited by DRI alone there were approximately 3,500 children of all ages including infants as young as one week old.[38] In Mombasa, a major city on the coast of Kenya, DRI attended a “Christmas Celebration”[39] in a local stadium organized by a private company, Talanta Kenya, for children in institutions. When we arrived, we saw over 3,000 children from different institutions in Mombasa. We were informed by the organizers that fifty institutions were invited. According to the organizers “there are more than one hundred registered institutions in Mombasa, but we cannot include them all, there are too many children.”

The Children Services Department, under the Ministry of Labor and Social Protection, is responsible for registering private institutions. Local child protection officers are in charge of supervising the private registered institutions. However, the CRC Committee expressed its concern given the fact that “the inspection and monitoring of the care provided at childcare institutions are weak, and there is no complaint mechanism through which children can denounce violence in care institutions.”[40] In line with the CRC Committee’s statement, most of the institutions that DRI visited stated that they were not regularly monitored.[41] Unregistered institutions operate under the radar and consequently are also never monitored.

Registered institutions are supposed to receive children only through a court order. However, a wide range of authorities and individuals, besides the courts, are sending children to institutions, including the police; local chiefs; the Kenya’s Children’s Department; the District Children’s Hospital; churches; and persons in the community who find children lost or in the streets.[42] All but two private institutions visited by DRI[43] reported that they received children that were not referred by courts but were brought instead by private individuals, local chiefs, or the police. At Flomina Children’s Home, we found a 6-month old baby who had been abandoned in a beauty salon and brought by a “good Samaritan” to the institution. According to the Director, they “just kept the baby.”[44]

- Lack of monitoring and action from authorities to stop abuses

“It is our responsibility to monitor institutions for children with disabilities, but we do not do it.” – Chief Program Officer, National Council for People with Disabilities

DRI met with the National Council for People with Disabilities who recognized that it is their responsibility to monitor institutions specifically for children with disabilities, but they do not do it.[45] The Chair of Association of Charitable Children’s Institutions (ACCIK), an organization that represents over one hundred institutions in Kenya, informed us that there is no supervision by the government of registered and unregistered institutions; “if you register or not, it makes no difference in terms of the government and supervision.”[46]

There have been several instances where abuses have been reported to local children authorities who have in turn failed to act. Stahili, an organization that is working towards deinstitutionalization in Kenya, stated that it has reported several cases to the children’s officers but they often “do nothing about it.” There is an institution with one hundred and eleven children near the city of Kisumu. According to Stahili, there were allegations of rape and sexual abuse at the facility and the authorities were informed.[47] However, the “local authority is not acting because it is very likely benefitting from the institution”[48] – making reference to possible bribes the government is receiving. According to the Chair of Community United for Advocacy for the Child, an organization in Mombasa that deals with institutions, some institutions are abusing the children. However, owners of institutions are often “very influential and when you identify a child is being abused and report, it goes to the legal system but the case does not go anywhere. The institution still remains open.”[49]

C. Abuses in institutions

In his report on the protection of children from torture, UN former Special Rapporteur on Torture Juan Méndez noted that “even very short periods of detention can undermine a child’s psychological and physical well-being and compromise cognitive development.”[50] Once a child is separated from his or her family and placed in an institution, he or she is subjected to an array of dangers that can be irreversible, including psychological damage from being raised in congregate care without stable emotional attachments, developmental delays, and permanent intellectual disability caused by neglect and a lack of social stimulation.[51] Children in institutions also face exploitation[52] and are at a “heightened risk of violence, abuse and acts of torture or cruel, inhuman or degrading treatment or punishment.”[53]

DRI investigators found inhuman and degrading conditions and practices that are dangerous and life- threatening. Practices we observed may amount to torture, including the lack of adequate medical care, the use of isolation rooms and physical restraint, and tolerance of conditions that allow physical and sexual abuse to occur. We found these problems especially within institutions for children with disabilities, which are consistently more abusive than other facilities. In the limited number of institutions the government has monitored, it has made similar findings. On May 2010, the Area Advisory Council of the Children’s services inspected the “Naivasha Orphans Rescue and Rehabilitation Centre” and found poorly maintained records of the children, unqualified staff, poor diet, inadequate medical care, and poor water and sanitation. The government also found a terminally ill girl who was immediately taken to hospital after having been bedridden.[54]

- Life threatening conditions

DRI found immediate life-threatening conditions and practices in three institutions, two of which are for children with disabilities: Compassionate Hands for the Disabled and Maji Mazuri. In both institutions, children are locked overnight in a room for thirteen hours or more.[55] At Compassionate Hands for the Disabled, up to four children sleep in one bed for those thirteen hours. Being locked up and unable to move puts the children’s lives at risk if there were to be a fire. At Maji Mazuri, a DRI expert found that:

“The light bulb was coated with dead bugs and dirt and was a potential fire hazard. The program director reported that the children are locked in the room at approximately 6 pm each night and the door was not opened until sometimes 7 am the next morning. The door to the room was of solid steel with a latch bolt. If there were a fire, the children would perish before assistance could be provided.”[56]

DRI visited Compassionate Hands for the Disabled twice, in June and November 2017. On both visits DRI observed feeding practices that put the children at risk of choking. In June 2017, DRI observed a four-year-old child feeding another child with cerebral palsy (pictured below) by pulling his head backwards and shoving food in his mouth, repeating the process before the child with cerebral palsy was done swallowing. He was unsupervised.

Compassionate Hands for the Disabled. Photo by DRI

The children with cerebral palsy were observed during lunchtime. Children with cerebral palsy commonly have feeding disorders and swallowing problems (dysphagia) that in many instances place them at risk for aspiration with oral feeding.[57] One child was being fed by another child who lives at the facility. Other children were being fed by caregivers who were placing heaping mounds of food on spoons into the child’s mouth. The children were unable to manage the large amount of food and were thrusting most back to the spoon with their tongue which was then scooped back into the child’s mouth.

At Compassionate Hands for the Disabled, DRI also found a child with “severe hydrocephalus” that has been untreated for years.[58] His condition has not been treated because, according to the institution, they do not have the monetary resources. According to a DRI expert, if “left untreated, progressive hydrocephalus may be fatal.”[59] Untreated hydrocephaly can also be extremely painful for the child.[60]At Canaan Orphanage, in Mombasa, we found thirty eight children crammed in two small rooms. This was not the only institution where we found overcrowding, as detailed in Section II.A.3. However, at Canaan Orphanage the rooms were not adequately ventilated and there were at least two children per bed, with some children sleeping on the floor. According to the manager, during rainy season the rooms would flood. Communicable diseases like malaria and cholera were common in the institution and spread easily due to the overcrowding and lack of ventilation. The institution reported that they did not have access to medications to treat these diseases. According to the manager, a six-month-old infant died in 2017 and at least three others had died in the last five years from malaria and cholera.

- Trafficking

DRI interviewed a Kenyan government official from the Ministry of Labor and Social Protection who said that “trafficking is very high” in institutions; “children are being recruited and they’re shipped out of the country with promises of better lives but they go and they end up in brothels where they are sexually exploited.”[61] This official mentioned that the Children Services Department is working with the Criminal Investigation Department to focus on orphanages “where children are being exploited.” The exploitation is in many cases being carried out by “foreigners.” According to the official, “people are paying to come, people are paying school fees for children and they are sexually exploiting them.”[62]

- Lack of staff and neglect

In every single institution DRI visited, we found that there were few staff taking care of the children. Moreover, staff was not trained and in several places we found teenagers taking care of other children. In half of the institutions, the ratio was one staff person for ten to fifteen children. In the other half of the institutions, we found a more extreme ratio of one staff person for thirty to forty children. These institutions were Happy Children’s Home, Canaan Orphanage (Mombasa), Salvation Army Institution (Mombasa), Flomina’s Children Home, Christ Chapel Children’s Home, Compassionate Hands for the Disabled, Baby Blessing Nursing Home, Dagoretti Rehabilitation Centre, Agape Hope Home, and Thika Rescue Center (public).

Severe lack of staff was especially dangerous in cases of institutions for babies. At Happy Life Children’s Home, there were sixty babies in total, divided in four rooms. The babies were lying down, crying or sleeping in rows of cribs. There were only two staff to “care” for all of the babies, and both were busy changing diapers or preparing feeding bottles. No staff was available to soothe the babies that were crying or to provide individualized attention. At Baby Blessing Nursing Home, there were thirty six babies lying in cribs. There was only one woman that was “caring” for all the babies. One baby that was merely one week old started crying; it took ten minutes for the woman to come and check on him, even after the person that was showing us around called her.

At Kenya Children’s Home, DRI found fifteen babies lying down on a blanket-covered floor with no stimulation. There was only one woman with the children and she was busy changing diapers. At Flomina Children’s Home, DRI found one “housemother” in charge of nine babies. When DRI arrived at the institution, we heard a baby crying for about five minutes. We thought the baby was alone until we walked in and saw the housemother lying down on a bed. It was only after we walked in that she got up to attend to the baby.

Kenya Children’s Home, Photo by DRI

At Flomina Children’s Home, there was one woman in charge of over forty children. Some of the children were running around, would fall, and start crying, but nobody would come to check on them. At Salvation Army institution in Mombasa we found forty young children, including babies, in one room watching television with only one woman with them. At Christ Chapel Children’s Home we found around 30 younger children in one room with one woman, just sitting in the room.

Nyumbani Village brings in some older women referred to as “grandmothers” to take care of the children. They take care of up to fifteen children that all live in a house together. “Grandmothers” taking care of the children are not paid by the institution. Besides taking care of the 15 children, they have to work the land to grow food for the house, cook, and clean. Some of the “grandmothers” are very old. Children mostly play outside on their own without supervision. According to a social worker from Nyumbani Village, “this is not a home, we cannot account for where all the children are at any given time.”

At Compassionate Hands for the Disabled, there were very few qualified staff members. During our June 2017 visit we saw two volunteers, two women and two men, who were wearing lab coats and referred to themselves as a doctor and a physiotherapist. The institution houses eighty seven children. The volunteers were supervising two women who were moving all the children into the rooms where they would lock them up for the rest of the evening until the next morning.

i. Impact of neglect

According to former Special Rapporteur on Torture Juan Méndez, emotional neglect as a result of lack of attachments to a consistent caregiver is one of the most pervasive and damaging types of abuse in social care settings:

“One of the most egregious forms of abuse in health and social care settings is unique to children. Numerous studies have documented that a child’s healthy development depends on the child’s ability to form emotional attachments to a consistent care-giver. […] Unfortunately, this fundamental need for connection is consistently not met in many institutions, leading to self-abuse, including children banging their head against walls or poking their eyes.”[63]

At Maji Mazuri DRI observed a young man with a disability rocking back and forth. At Compassionate Hands for the Disabled we saw one child banging his head on the wall both times we visited the institution, in June and in November 2017. At Happy Children’s Home several children were rocking back and forth. We also found a child that was three years old but looked as small as a one year old and was lying in a crib with the other babies. One baby girl was picked up by a staff to change her and she could not hold her head and arms up, so they were just dangling.[64]

The former Rapporteur on Torture has also found that children deprived of liberty are at a heightened risk of suffering depression and anxiety, and frequently exhibit symptoms consistent with post-traumatic stress disorder.[65] However, children are not receiving adequate psychological support in institutions. In one institution, the director told us that the only emotional support the children get is from herself, though she is not a trained psychologist.[66] In Nyumbani Village there were two psychologists for one thousand children. A Chief Program Officer from the National Council for Persons with Disabilities (NCPWD) acknowledged that the “mental health system is extremely poor” in Kenya and there is little understanding on mental health care and how to provide it adequately.[67]

- Inhumane and degrading conditions

In several institutions children are essentially warehoused. DRI found poor water and sanitation and overcrowding in most of the institutions we visited.[68] More than half of the institutions were severely overcrowded, with twenty to thirty children sleeping in one room.[69] In various institutions, there were more children than beds so the children had to share mattresses.[70] Compassionate Hands for the Disabled has a capacity of fifty but it houses eighty five. In one room, there were ten beds for thirty children. By 5 pm all the children were being put to bed. According to one volunteer, they are left in their beds from 5 pm until 6 am the next day. There were up to four children on one mattress put to sleep together (pictured below), where they would remain for at least thirteen hours, until the next morning. During the night these children would soil or wet the beds they share.

Compassionate Hands for the Disabled, Photo by DRI

At Compassionate Hands for the Disabled, DRI also saw how some children with cerebral palsy had a plate put in front of them and left to feed themselves, even though they were tied to chairs and some of them could not hold a spoon. Children tried to eat but some of them were physically unable. Their mouths and faces were covered in food. Flies were flying all around them and landing in their mouths and on their faces. They were dressed in dirty and ragged uniforms, many with only soiled socks for footwear. All the clothes were gender neutral and the boys and girls had short haircuts alike, making it difficult to tell who was a boy and who was a girl.[71]

Several facilities were also in very bad condition. Some of them were makeshift rooms without an adequate structure. The rooms were small and children were crowded in them. At Baby Blessing Children’s Home, DRI found thirty six babies crammed in two small rooms. In a separate building, there were forty children living in three small bedrooms; the rooms had no windows and, as a result, the illumination and ventilation were very poor.[72] At Agape Hope Home, several buildings were made of wood and there were leaks in the ceilings and walls when it rained. Several buildings had dirt floors.

One particularly disturbing institution was Dagoretti Rehabilitation Centre. This institution was practically a slum with several rooms and passages where five hundred children were crammed in extremely unhygienic conditions. One of the older children was guarding the door with a machete and a whip to prevent the children from leaving. The most dangerous aspect of this facility was that rehabilitating drug addicts and former prisoners are crammed together with girls and teenagers. Several adult men are also roaming the institution.

At Canaan Orphanage in Mombasa there is also severe overcrowding. Thirty eight children sleep in two rooms. There are five bunkbeds in each room so two children sleep in one bed and some children sleep on the floor. According to the Director, during the rainy season the rooms flood. There is no adequate ventilation in these rooms, despite the fact that the institution is on the coast and it gets very hot and humid. Other rooms in the institution had a fan, but not the rooms where the children were sleeping. The facility had two bathrooms in very bad conditions that had a stench of urine and feces.

- Use of isolation rooms and restraints

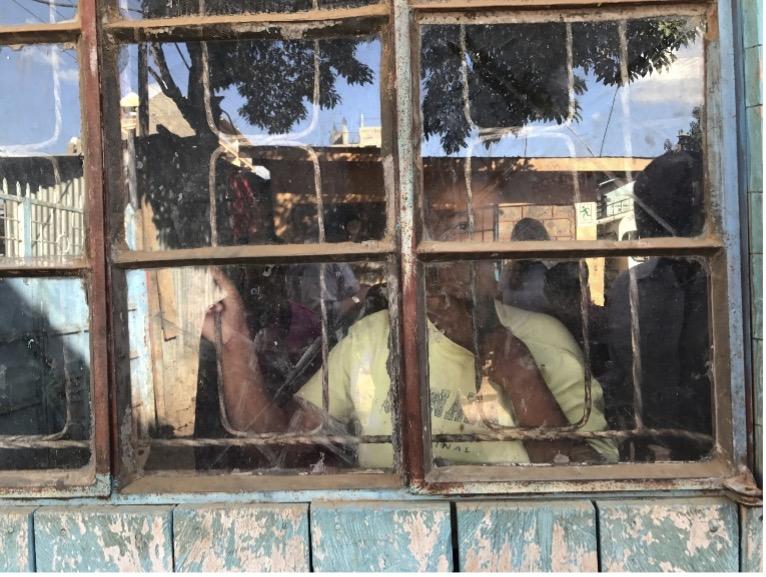

At Christ Chapel Children’s Home, the director told us that when young children “make mistakes,” they are punished by being locked in a dark room with no windows. They remain there for a whole day, are not allowed to play inside and are given no food. According to the Director, “the children are terrified of the room and none of them ever wants to be there.”[73] In a meeting later with the government, the Director of Children’s Services stated in relation to this practice: “that is torture.” At Maji Mazuri, an institution for children with disabilities, we saw one child, Leila (pictured below), locked in a shack where old furniture was stored. When we noticed her in the window, the door was opened and we were told she prefers to be in the room by herself. The door was closed and locked afterwards.[74]

Maji Mazuri, Photo by DRI

At two institutions for children with disabilities, Maji Mazuri and Compassionate Hands for the Disabled, we found children tied to wheelchairs. Staff maintained that they had to be tied down, otherwise they might fall, which suggested that these children remain tied down for prolonged periods of time. At Maji Mazuri, we found a young man tied to a wheelchair with pieces of cloth across his waist. He was standing up with the chair attached trying to push open the gate to the outside.

At Compassionate Hands for the Disabled we also found children in hand splints for prolonged periods of time, a form of restraint. When questioned, the “physiotherapist” reported that the children wear the hand splints throughout the day to “straighten” their hands. There were no documents to indicate an assessment had been conducted to determine why the children needed the hand splints or the benefit to the child of wearing the splints.

Additionally, at Compassionate Hands for the Disabled six children were tied to a standing board in what seemed to be a very painful position, to allegedly keep their legs straight. The children remained in this position for the entire duration of our visit, which was over three hours. By the end of our visit the children were crying out in pain and begging us to release them. The “physiotherapist” told us that the children were going to remain in that position for another couple of hours. After a child begged to be released, the “physiotherapist” replied “if you keep crying, I will keep you here longer.”

The children were observed crying and expressing discomfort, but were not provided an alternate position during the visit. Many of the children in these standing devices were observed to be on “tiptoes” or without their feet touching the bottom of the device, indicating inappropriate positioning and inadequate support, potentially causing additional pain and discomfort.

- Inadequate medical care

In three institutions, including two for children with disabilities, DRI witnessed instances of gross medical neglect and inadequate care. In the institutions for children with disabilities we found use of inadequate wheelchairs that could cause pain. Wheelchairs were ill-fitting and did not appear to have been designed specifically for the child in order to support contractures and reduce further deformity. Many children observed were noted to have knees rubbing together, elbows rubbing against armrests and lap trays, and legs extended and crossed without proper orthotic cushions, supports, or wedges that would “relieve the pressure and reduce the risk of skin breakdown and pain associated with decreased range of motion and limitation in mobility.”[75]

At Maji Mazuri we could hear one child’s bruxism – grinding of the teeth – upon exiting the building to the courtyard where the child was sitting in a wheelchair. He was sitting in a wheelchair, crying and grinding his teeth (pictured below). He rolled his chair closer to us and twisted to the point that his legs were caught between the seat back and the seat. His crying and bruxism intensified. He continued to try and get out of his chair and was sitting high on the back which posed an imminent risk of injury with the chair tipping and him falling to the ground. A staff person grudgingly attempted to assist him without taking the lap tray off the chair in order to safely adjust him to a front-facing position, again risking injury.

In both institutions for children with disabilities there were no medication records at all despite the fact that anti-epileptic medications and anti-psychotics were being administered to the children. According to DRI expert Melanie Reeves Miller, there were no assessments or psychiatric diagnoses for prescribing the medication, no assessments of the the positive or negative effects the medication was having on the children, and no lab tests to monitor the levels of the medications for therapeutic ranges or toxicity. At Maji Mazuri, all the medications were mixed in a bucket including loose tablets, with no boxes to identify the medication. At Compassionate Hands for the Disabled, the “doctor” informed us that one child (who is eight years old) was given 10mg per day of Risperdal (an anti-psychotic medication) due to “hyperactive behaviors.” Yet again, “there was no evidence of a psychiatric assessment to support a mental health diagnosis that would require a dosage of nearly four times the recommended adult range.”[76]

Maji Mazuri, Photo by DRI