ALTERNATIVE REPORT BY MEXICAN CIVIL SOCIETY ORGANIZATIONS SUBMITTED TO THE COMMITTEE ON THE RIGHTS OF PERSONS WITH DISABILITIES

2014-2019

TABLE OF CONTENTS

- EXECUTIVE SUMMARY

- RECOMMENDATIONS TO THE MEXICAN STATE

- VIOLATIONS TO RIGHTS RECOGNIZED IN THE CONVENTION ON THE RIGHTS OF PERSONS WITH DISABILITIES

- Article 5. Equality and non-discrimination

- Article 6. Women with disabilities

- Article 10. Right to life

- Article 12. Equal recognition before the law

- Article 13. Access to justice

- Article 14. Liberty and security of the person

- Article 15. Freedom from torture or cruel, inhuman or degrading treatment or punishment

- Article 19. Living independently and being included in the community

- Article 23. Respect for home and the family

- Article 24. Education

- Article 25. Health

- Article 27. Work and employment

- Article 33. National implementation and monitoring

ABBREVIATIONS

CRPD - Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities

CRPD - Committee United Nations Committee on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities

CRC - Convention on the Rights of the Child

CRC - Committee United Nations Committee on the Rights of the Child

DRI - Disability Rights International

ECT - Electroconvulsive therapy

ACRONYMS IN SPANISH

CAIS - Assistance and Social Integration Center

CONADIS - National Council for the Development and Inclusion of Persons with Disabilities

CRREAD - Rehabilitation and Recovery Center for Drug Addicts and Alcoholics

ENADID - National Survey of Demographic Dynamics

ENDIREH - National Survey on the Dynamics of Relationships in Households

ENADIS - National Survey on Discrimination

GIRE - Information Group on Elected Reproduction

LGDNNA - General Law on the Rights of Children

IMSS - Mexican Institute of Social Security

INEGI - National Institute of Statistic and Geography

ISSSTE - Institute of Security and Social Services of State Workers

NOM-025 - The Official Mexican Standard NOM-025-SSA2-2014 for the provision of health services in comprehensive medical-psychiatric hospital care units

REDIM - Mexico Children’s Rights Network

SIPINNA - Executive Secretary of the National System for the Integral Protection of Children and Adolescents

I. EXECUTIVE SUMMARY

This alternative report is a collaboration between the “Colectivo Chuhcán” A.C., Disability Rights International (“DRI”), EQUIS Justice for Women A.C. (“EQUIS”), Information Group on Elected Reproduction (“GIRE”), Transversal, Action on the Rights of People with Disabilities A.C. and the Mexico Children’s Rights Network (“REDIM”).[1]

This report is submitted to the Committee on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities (hereinafter “The Committee” or “CRPD Committee”) for the working group of the pre-session 12, which will be held from September 23 to 27, 2019, to determine the list of issues for the CRPD Committee’s evaluation of Mexico.

Among the findings that are addressed in this report, the participating organizations found that persons with disabilities are segregated and abused in institutions, suffer violence in family and in community settings; are discriminated at work, at school and in their families; cannot exercise their right to legal capacity under Mexican law; and cannot access justice.

Persons with disabilities, including children, are detained because of their disability in highly dangerous institutions and may remain there for life. In the institutions, this population faces the risk of death, torture, use of isolation rooms, physical restraints, sexual and physical abuse and forced sterilizations. They cannot report abuses because there are no reporting mechanisms that could allow them to access justice.

According to official estimates, 26,000 children are detained in institutions. However, according to an official from the System for the Protection of Childhood, this number of children in institutions may be as high as 140,000. Children are increasingly detained in smaller institutions that may be intended to be family-like. However, these children are still raised without the opportunity to establish any permanent family bonds and these facilities still operate like institutions. Adults with disabilities are also being detained in institutions in the middle of urban areas, but these environments are still segregated from the community.

This report is based on the Concluding Observations on the Initial Report of Mexico of 2014 issued by the CRPD Committee,[2] the report sent by the Mexican State,[3] investigations carried out by the organizations that submit this report and testimonies of the persons with psychosocial disabilities.

The Report analyzes violations to the following CRPD provisions: Equality and non-discrimination (Article 5), Women with disabilities (Article 6), Right to Life (Article 10), Equal Recognition before the Law (Article 12), Access to justice (Article 13), Liberty and security of the person (Article 14), Freedom from torture or inhuman or degrading treatment or punishment (Article 15), Right to Live Independently and to being included in the community ( Article 19), Respect for home and a family (Article 23), Education (Article 24), Health (Article 25), Work and employment (Article 27) and National implementation and monitoring (Article 33).

II. RECOMMENDATIONS TO THE MEXICAN STATE

Article 5. Equality and non-discrimination

- Establish concrete actions and budgets in terms of equality and non-discrimination towards persons with disabilities.

Article 6. Women with disabilities

- Generate reliable statistics that report on the situation of violence experienced by girls and women with disabilities in Mexico.

Article 10. Right to life

- Investigate and prosecute all those responsible for the death of persons with disabilities in institutions.

Article 12. Equal recognition before the law

- Modify the legislation that allows the legal incompetence of persons with disabilities.

Article 13 – Access to justice

- Allocate a budget for the improvement of the mechanisms of access to justice for persons with disabilities.

- Conduct trainings for the judicial powers regarding the rights of persons with disabilities in accordance with the provisions of the CRPD.

- Implement mechanisms within the judicial powers to guarantee that persons with disabilities are attended by jurisdictional staff trained in the human rights of persons with disabilities.

- Implement access to justice mechanisms for persons who are living in institutions.

Article 14. Liberty and security of person

- Eliminate the laws that allow the arbitrary detention of persons with disabilities.

- Implement a mechanism to learn about the situation of persons with disabilities who are living in prisons.

- Implement mechanisms that allow access to justice for persons with disabilities who are in detention centers according to the different needs of their population.

- Implement a social reintegration program for persons with disabilities who are in prisons.

Article 15. Freedom of torture or cruel, inhuman or degrading treatment or punishment

- Take immediate action to investigate and punish the persons responsible for inflicting cruel, inhuman and degrading treatment on persons with disabilities within the institutions.

- Eliminate the legislation that allows the realization of irreversible treatments for persons with disabilities such as forced sterilization, surgical interventions in children, electroshock therapies, among other procedures.

- Legislative power: Eliminate the assumption of "mental retardation" from informative Appendix "A" of NOM 005, considered as an indicator to be a candidate for the Bilateral Tubular Occlusion procedure.

Article 19. Living independently and being included in the community

- Adopt legislative and financial measures to create community-based services for persons with disabilities.

- Establish a strategy for the deinstitutionalization of persons with disabilities, including concrete actions and with the necessary budget to achieve it.

Article 23 – Respect for home and the family

- Provide the necessary support so that persons with disabilities can exercise their right to have a family.

- Create alternative care programs to allow children with disabilities to exercise their right to live in a family and not in an institution.

Article 24. Education

- Ensure appropriate measures for all children with disabilities can have quality inclusive education.

Article 25. Health

Federal and local health institutions

- Ensure that places, services, materials and information on contraceptives and reproductive health are friendly and accessible for persons with disabilities.

- Harmonize criminal legislation and administrative instruments on abortion due to rape with the General Law of Victims and NOM 046, eliminating the requirements of time, complaint and prior authorization and ensure access without discrimination for persons with disabilities to such service.

- Guarantee emergency medical care in cases of sexual violence for persons with disabilities, consisting of emergency contraception, prophylaxis to prevent sexually transmitted infections and termination of pregnancy, as well as their registration, disaggregated by legal cause, age, ethnicity and disability, if any.

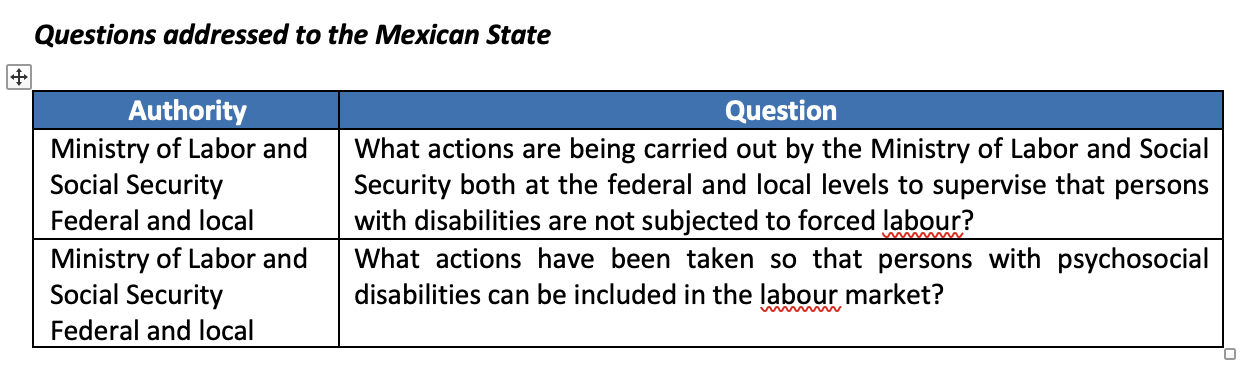

Article 27 – Work and employment

- Establish mechanisms to protect persons with disabilities from any forced labour.

- Establish employment integration strategies for persons with psychosocial disabilities.

Article 33 – National implementation and monitoring

- Strengthen the existing mechanisms related to the implementation of the Convention, such as “CONADIS”.

VIOLATIONS TO RIGHTS RECOGNIZED IN THE CONVENTION ON THE RIGHTS OF PERSONS WITH DISABILITIES

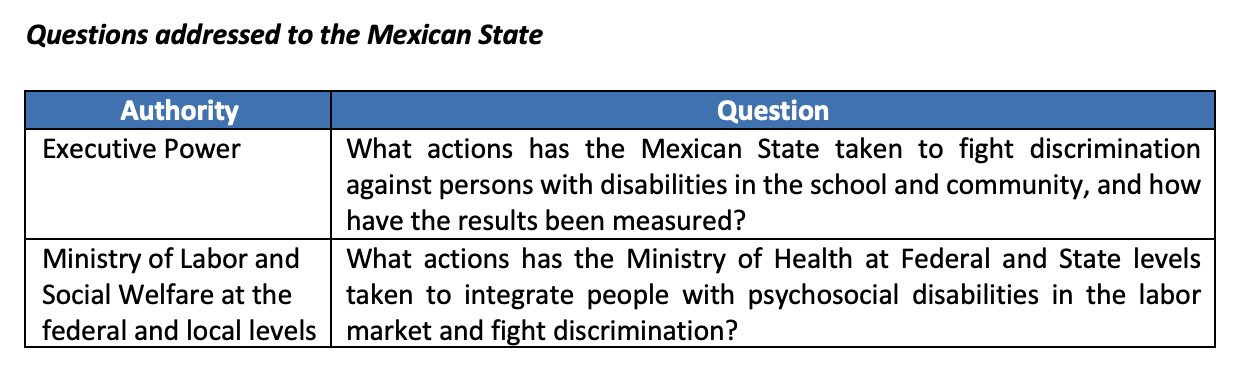

Article 5. Equality and non-discrimination

The CRPD establishes that States Parties shall prohibit “all discrimination on the basis of disability and guarantee to persons with disabilities equal and effective legal protection against discrimination on all grounds.”[4] In its concluding observations, the Committee recommended that Mexico establish “specific budget lines to meet its targets in respect of equality, as well as specific actions to combat cases of intersectional discrimination.”[5]

The National Survey on Discrimination (ENADIS 2017) estimated that there are about 157,000 adolescents with disabilities -between 12 and 17 years, of which, 48.1% (75 thousand) claim to have been discriminated at least in one occasion in the school setting (25.3%), in the street or public transportation system (16.9%), and in the family (6.2%). People with psychosocial disabilities from the “Colectivo Chuhcán” said they had been discriminated, particularly in the workplace.

“I went to look for a job once. I have multiple scars on my arms, the person there could see the scars on my hand, and when she saw it, she told me that I could not apply.”

“In a job they found out that I had schizophrenia and my boss was afraid of me […] and she wanted to fire me [...]. She ordered me to do many more things than the rest to fire me.”

“For fear of being fired in my job, I have not said that I have a disability. The job is often too much for me. I am a responsible person, the disability does not make us irresponsible, but I feel overwhelmed, and I feel that I cannot reach my goals.”

“I was discriminated in my last job. My brother, who was my boss at the time, did not understand the stress I was dealing with. By being his assistant, he gave me extra work, and, the rest of the coworkers, seeing this situation, did not respect me.”

Testimonies from members of the Colectivo Chuhcán, June 2019.

People with psychosocial disabilities from the “Colectivo Chuhcán” also said they had been discriminated by their families, in the public transportation system and in their communities because of the stigma and lack of information about psychosocial disability.

“I think there is a lot of ignorance about [psychosocial] disability, [...] there is a lot of prejudice, and there is too much stigma.”

“I have been discriminated in the public transport [...] by the police. There are public transport officials who, when I say I have a disability [...] they feel angry when I say it, because they think I am lying because my disability is not visible, and I feel angry that they do not believe us.”

“In general, in the society, if they do not see you with a physical disability, they think you have nothing. Same thing happened to me in the subway, they do not want to let me use my disability discount card because my disability is not visible. That is why there needs to be a lot of information about psychosocial disability.”

“There is a lot of ignorance, starting with the family [...]. There is a lot of ignorance, and my parents do not want to talk about my disability with the family.”

“Ignorance begins with the family. My mother did not want anyone to find out that I had schizophrenia, she spoke about it as a secret and treated it as something bad. When I was taking medicine to sleep, I was sleepy all the time and when people went to our house, my parents told me: better go to your room, do not come out.”

“My family tried to ‘help’ me by hiding me. If my own family, who has heard programs about schizophrenia, who knows about the issue, and understands it, treats me like that, you can imagine how society and the neighbors, who know nothing about schizophrenia, treat me.”

“In my family they say that I am handicapped. They cling to that term. They say that I do not understand the reality, that I am unconscious and they say that I cannot understand and, therefore, my decisions are incorrect. They act in a prejudiced way.”

Testimonies from members of the Colectivo Chuhcan, June 2019.

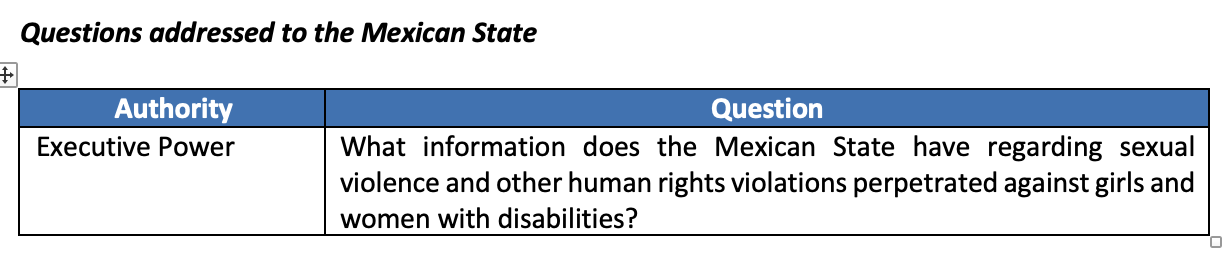

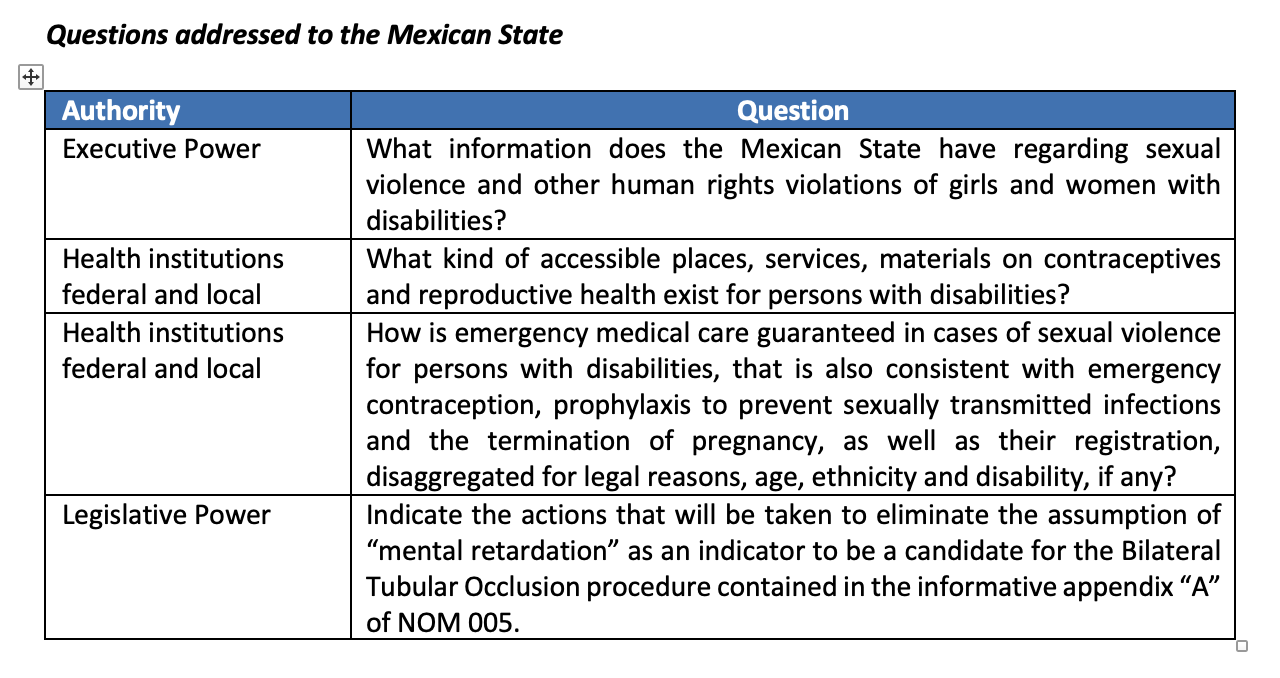

Article 6. Women with disabilities

In its concluding observations, the CRPD Committee recommended Mexico to “put into effect the legislation and all of the programmes and actions targeting women and girls with disabilities, including corrective measures and affirmative action, to eradicate discrimination in all aspects of life.”[6] Likewise, the Committee recommended to the State to “systematically compile data and statistics on the situation of women and girls with disabilities, together with indicators for the evaluation of intersectional discrimination.”[7]

In Mexico, according to data from the National Survey of Demographic Dynamics (“ENADID” 2014), around 7.1 million people lived with some disability, 3.8 million were women.[8] Despite these numbers, there is no data on the violence and human rights violations that women with disabilities experience. In fact, the National Survey on the Dynamics of Relationships in Households (“ENDIREH” 2016) that measures, among other things, sexual violence against women, does not specify whether the women interviewed had any disability, which prevents them from knowing the incidence of violence towards this population. In addition, the National Institute of Statistic and Geography “INEGI” considers disability as a reason to suspend a survey and leaves the decision to suspend it at the discretion of the person conducting the survey.[9] Not collecting information on women with disabilities is discriminatory and contributes to the invisibility of the violence they face.

In Mexico there is no data that shows the situation of violence faced by women with disabilities, but the CRPD recognizes that women and girls with disabilities are usually exposed to a greater risk of violence inside and outside the home, injury or abuse, abandonment or negligent treatment, mistreatment or exploitation. The lack of data on the situation of girls and women with disabilities prevents the State from developing and implementing public policies that prevent and address violence against women with disabilities and is a sign of the lack of interest of the Mexican State in this population.

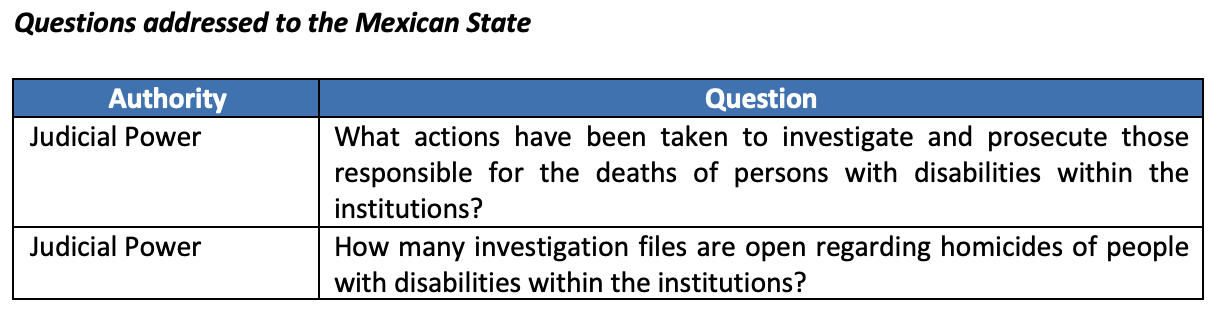

Article 10. Right to life

The CRPD establishes that “States Parties reaffirm that every human being has the inherent right to life and shall take all necessary measures to ensure its effective enjoyment by persons with disabilities.”[10] Any person locked up in an institution in Mexico is at risk of dying due to the inherent dangers present in Mexican facilities. DRI has found that facilities in Mexico have dangerously unhygienic and degrading conditions, no adequate treatment to deal with diseases and contagious infections, no adequate standards in the administration of treatments, severe neglect –which is particularly dangerous in the case of children, use of cages and restraints in dangerous positions, among others. Two examples of this are “Casa Esperanza” in Mexico City, and “Casa Gabriel” in Ensenada, Baja California. Both are private institutions that detained children and adults with disabilities, some of whom were sent by government authorities.

At “Casa Esperanza”, an institution with 37 children and adults with disabilities that DRI reported to the CRPD Committee for the evaluation of Mexico in 2014, DRI witnessed children and adults tied up in very painful positions. We received information that at least one person died while he was tied up. Mexico’s reaction to this abusive institution was to send the 37 children and adults to other institutions. At least one young man and one young woman (both in their early thirties) died within six months of being transferred. According to government officials, the deaths were caused by severe malnourishment which originated in “Casa Esperanza” and was inadequately treated at the institutions they were transferred to.

Staff at “Casa Gabriel”, a private institution for children with disabilities in Ensenada, told DRI that two girls, one boy and one young adult woman –aged 12 to 22 years old, died within days of each other in February 2018. All had been fed with feeding tubes. Staff confided to us that “complications” with feeding tubes were the cause of their deaths. Another girl and boy died in November and December 2017. In total, 6 children died in a period of four months. The total population of the institution at the time was around 25 children and adults, which means that in a period of four months, a quarter of the population died. Despite this high mortality rate, the State has not opened an investigation regarding the deaths.

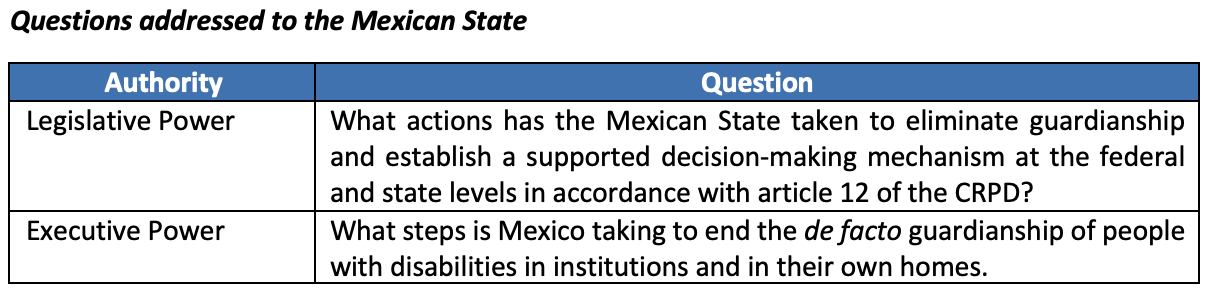

Article 12. Equal recognition before the law

The CRPD recognizes that persons with disabilities have legal capacity.[11] In its Concluding Observations, the CRPD Committee expressed to Mexico its concern about the “lack of measures to repeal the declaration of legal incompetence and the limitations on the legal capacity of a person on the grounds of disability”[12] and urged the Mexican State to suspend “any legislative reform that would perpetuate a system of substitute decision-making and to take steps to adopt laws and policies that replace the substitute decision-making system with a supported decision-making model that upholds the autonomy and wishes of the persons concerned, regardless of the degree of disability.”[13]

a. Denial of legal capacity

Through its legal framework, Mexico automatically and completely continues to deny persons with disabilities their right to legal capacity. Mexico’s Civil Code establishes that adults “[…] with diminished or disturbed intelligence, even though they may have lucid intervals; and those who suffer from any disease or condition caused by persistent impairment of a physical, psychological or sensory nature […]” have “natural and legal incapacity.”[14]

DRI analyzed the civil codes of the 32 states and found that all have provisions that establish a guardianship regime for people with disabilities.[15] In the case of persons with disabilities who live in institutions, they are automatically put under a de facto guardianship of the facilities’ director. In practical terms this means that 1) adults with disabilities are never taken to a judge that can review their guardianship and detention in an institution; 2) it becomes even harder for persons with disabilities in institutions to judicially challenge an assumed guardianship and a detention, and 3) they are unable to access justice on their own.

According to the Colectivo Chuhcan, people with disabilities in Mexico are also subject to a de facto guardianship by their families and government officials.

“I am fighting a brother in court for a testamentary succession and what I have observed is that he tells the authorities that I must be considered a minor because I have schizophrenia and many authorities agree with him.”

“My sister handles my disability pension card, so that I cannot spend the money.”

“My family handles the medication and they do not want to give it to me, and it should not be that way, it should not be.”

“My mother wants to inherit her house to me but my brothers do not agree because they are afraid that in a crisis I will give it away, and they want to 'protect me.' They do not want her to make her will leaving me the house [...] I do not know what will happen when my mother is no longer here.”

“A year ago my mother died and I had to fight to get a pension I was entitled to because they [Social Security Institute staff] said I did not have the right to it because of the disability.”

Testimonies from members of the Colectivo Chuhcán, June 2019.

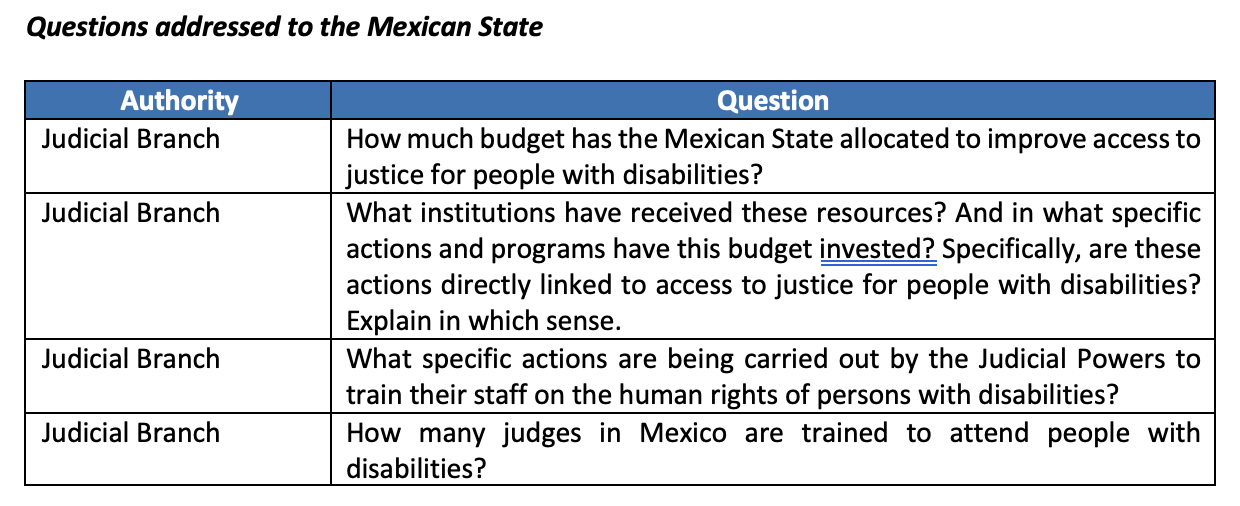

Article 13. Access to justice

The Convention establishes that the States shall “ensure effective access to justice for persons with disabilities on an equal basis with others.”[16] However, children and adults in institutions who are locked up lose their rights including their right to legal capacity –the legal ability to make decisions over their lives and exercise their rights. As a result, people in institutions are unable to file complaints and access courts. This automatically entails an impossibility to access justice.

The Convention also establishes that States shall promote “appropriate training for those working in the field of administration of justice.”[17] EQUIS Justice for Women provided legal representation to Leti – a poor indigenous woman with an intellectual disability – who was raped.[18] In the judgment, the judge considered that “individuals with mental retardation are at a higher risk of exploitation or physical or sexual abuse because of their intellectual deficiency, which leads to a decrease in the ability to adapt to the daily demands of a normal social environment.”[19] The prejudices underlying this judgment motivated an investigation[20] on the Judicial Branch’s obligation to train its officials on the rights of persons with disabilities and access to justice. The investigation revealed the systemic failure to fulfil this obligation.

In terms of budget, for example, it is estimated that from 2008 to 2017, national expenditure on disability training represented less than 1% of the budget allocated to overall judicial training.[21] Nine of the 32 states (Aguascalientes, Chiapas, Chihuahua, Guerrero, Jalisco, Puebla, San Luis Potosi, Tabasco and Zacatecas) did not allocate any budget to the subject, and other 16 states have no information about it.

In the last 10 years, no judicial branch trained its staff continuously on the rights of persons with disabilities.[22] This situation did not change significantly over this decade, not even with highly relevant normative advances that brought important legal changes, such as the entry into force of the Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities in 2008, and the Constitutional Reform on Human Rights in 2011, the year in which the General Law for the Inclusion of Persons with Disabilities was also approved.

Seven states (Aguascalientes, Baja California Sur, Guerrero, Jalisco, Oaxaca, San Luis Potosi and Tamaulipas) did not carry out any activity to train their judicial staff on disability rights. The activities reported as training are sporadic, disjointed, poorly implemented[23] and with little participation of the staff. It is estimated that only 13.7% of judges and 10.7% of magistrates have had any training activities on this issue. However, we cannot guarantee the level of training of these judges, because the trainings had no evaluation criteria, some included topics that were contrary to the human rights and were taught by teachers with little specialized knowledge on the issue.

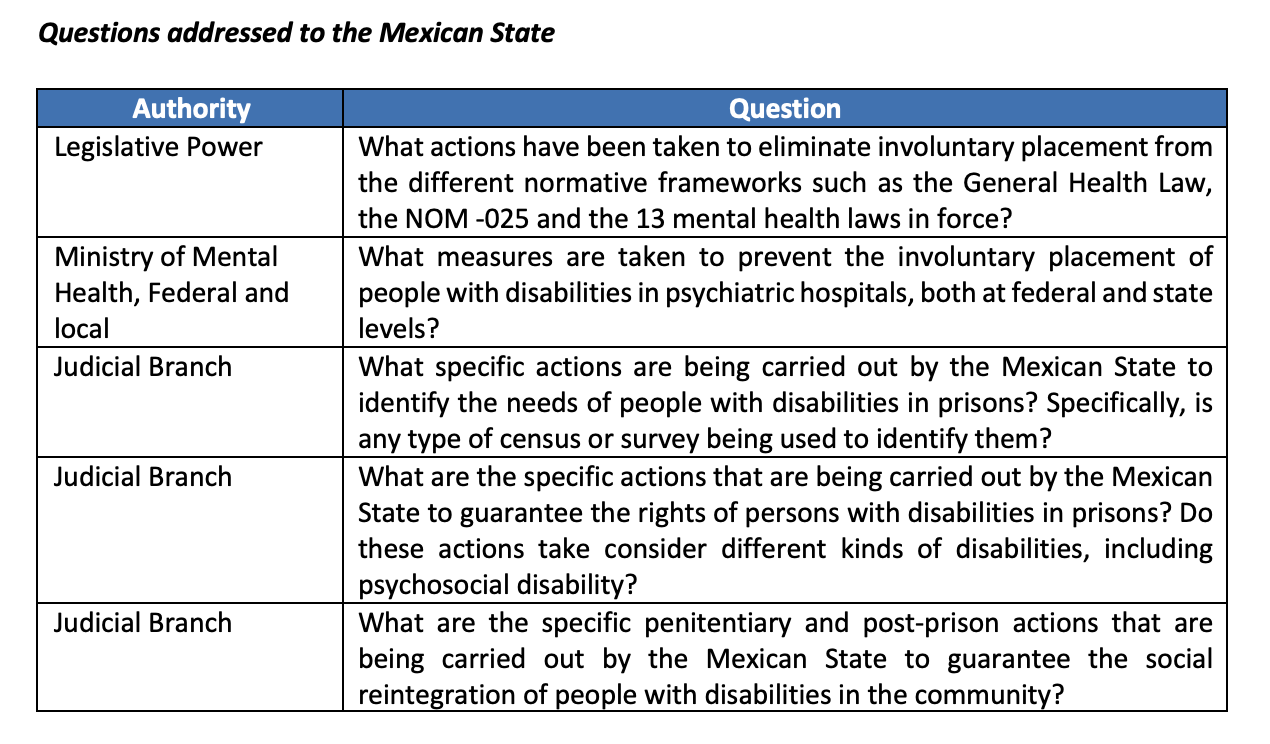

Article 14. Liberty and security of the person

The CRPD has affirmed that deprivation of liberty on the grounds of disability is discriminatory and incompatible with recognized international human rights standards for persons with disabilities. Article 14 of the CRPD states that “the existence of a disability shall in no case justify a deprivation of liberty.”[24] The interpretation of the CRPD Committee is unequivocal: any involuntary and / or prolonged detention for reasons of disability is contrary to the CRPD and should be considered unjustified and, therefore, arbitrary.[25] In its Concluding Observations to Mexico, the CRPD Committee expressed its concern that Mexican legislation “authorizes deprivation of liberty in the case of persons with intellectual and psychological disabilities, on the ground of their disability; in particular, that provision is made for their confinement in psychiatric institutions in the context of medical or psychiatric treatment.”[26]

In 2014, the CRPD Committee urged the Mexican government to eliminate “security measures that mandate medical and psychiatric inpatient treatment and promote alternatives that comply with articles 14 and 19 of the Convention; Repeal legislation permitting detention on grounds of disability and ensure that all mental health services are provided based on the free and informed consent of the person concerned.”[27] However, current Mexican laws allow for the involuntary placement of persons with disabilities in institutions. In practice, DRI found that people with disabilities can be arbitrarily detained in unregulated, unregistered, private facilities, by any private person.

a. Involuntary placement and arbitrary detention

There are 13 Mental Health State Laws in force that allow involuntary placement,[28] contrary to the CRPD. The General Health Law and the Official Mexican Standard NOM-025-SSA2-2014 for the provision of health services in comprehensive medical-psychiatric hospital care units (hereinafter “NOM-025”) establish that the person or their representative has a right to informed consent, except in cases of involuntary placement.[29]

NOM-025 establishes that, in case of ‘emergency,’ a person can be detained in a psychiatric facility “by written indication of the specialists [...], requiring the signature of the responsible relative who is in agreement with the placement […].[30] The regulation establishes that the detention will be reviewed within the next 15 days to determine if the person must remain in the institution.[31] NOM-025 also mentions that, “as soon as the patient’s condition allows it, he or she will be informed of his situation of involuntary commitment so that, if appropriate, he can give his free and informed consent and his status can change to voluntary admission.”[32]

According to the Colectivo Chuhcan, people with psychosocial disabilities are detained involuntarily in psychiatric institutions with the consent of their relatives.

“I was hospitalized twice against my will.”

“During the last crisis I had, my family wanted to hospitalize me, but fortunately I did not let them, but they threatened me that they wanted to hospitalize me. In other occasions, they have hospitalized me against my will.”

Testimonies from members of the Colectivo Chuhcán, June 2019.

DRI found people with disabilities detained without their consent in “rehabilitation centers” on the border with the United States (USA). These rehabilitation centers are for people with addiction problems but in practice they detain minors, people with disabilities and deported persons from the USA.

“These rehabilitation centers do not have any sort of screening, keep people against their will and make people with intellectual disabilities sign contracts to detain them with their ‘consent.’ In one case a facility told [Al Otro Lado that a] person had signed a contract to be there. They had him doing handyman work because nobody was paying for him to be at the rehabilitation center. When [Al Otro Lado] saw him in the facility, he had his hands covered in urine and had no shoes on. This is a man who was [eventually brought] to the border crossing point, it was raining and there were puddles and he needed to hold [someone’s] hand and was jumping over the puddles. He clearly had a type of disability but was nevertheless forced to sign a contract and he probably was not explained what that meant.”

Interview with Mexico Director of Al Otro Lado

People are mostly taken to these rehabilitation centers by police, who picks them up from the street. In practice, there is no need for a judicial order to forcibly place people in these facilities.[33] According to a supervisor at “CRREAD Cañón Rosarito”, “it’s mostly the police that brings people here. They get tired of the people hanging around in the streets. They want to have the streets clean for tourists so they pick them up, gather them and bring them to us.”[34]

b. Arbitrary detention in unregulated facilities

Mexican laws are in violation of the CRPD but in practice, the procedures they establish to detain a person without their consent are not even enforced. People with disabilities can be arbitrarily detained in unregulated, unregistered, private facilities, by any private person. For instance, in the state of Baja California, DRI found two institutions operating without a license that arbitrarily detained children and adults with disabilities –some of whom were sent by the government. DRI visited a private facility that locked-up minors, adults with drug and alcohol abuse problems and adults with disabilities, all mixed together. The institution had no registration or legal authority to operate.

Another institution was operating in a dilapidated house and where children and adults with disabilities were detained and mixed together. The government sent children to this institution for months, despite it being unlicensed. When DRI visited it, in November 2018, the government was removing the children because they were mixed with adults, not because the institution had no registration. In fact, according to the director, the children were leaving but the adults with disabilities were going to stay.

c. Stigmatization of people with disabilities in detention centers

“EQUIS” requested information from all prison authorities in the country about what they considered a disability and the types of disabilities present in detention centers. They received responses from 24 authorities.[35] In the definitions provided by authorities from several states, the medical model prevails and is focused on the deficiency of the person, and not on the interaction of it with their context.[36] Also, EQUIS observed some responses contrary to the principle of recognition of the autonomy of persons with disabilities -established in the CRPD, with phrases such as “those that cannot take care of themselves (...).” Five prison authorities[37] responded that the determination of a disability is made through a medical evaluation. This is problematic because it focuses on the ‘deficiencies’ of the person and does not consider social barriers.[38]

Questions addressed to the Mexican State

Authority

Question

Legislative Power

What actions have been taken to eliminate involuntary placement from the different normative frameworks such as the General Health Law, the NOM -025 and the 13 mental health laws in force?

Ministry of Mental Health, Federal and local

What measures are taken to prevent the involuntary placement of people with disabilities in psychiatric hospitals, both at federal and state levels?

Judicial Branch

What specific actions are being carried out by the Mexican State to identify the needs of people with disabilities in prisons? Specifically, is any type of census or survey being used to identify them?

Judicial Branch

What are the specific actions that are being carried out by the Mexican State to guarantee the rights of persons with disabilities in prisons? Do these actions take consider different kinds of disabilities, including psychosocial disability?

Judicial Branch

What are the specific penitentiary and post-prison actions that are being carried out by the Mexican State to guarantee the social reintegration of people with disabilities in the community?

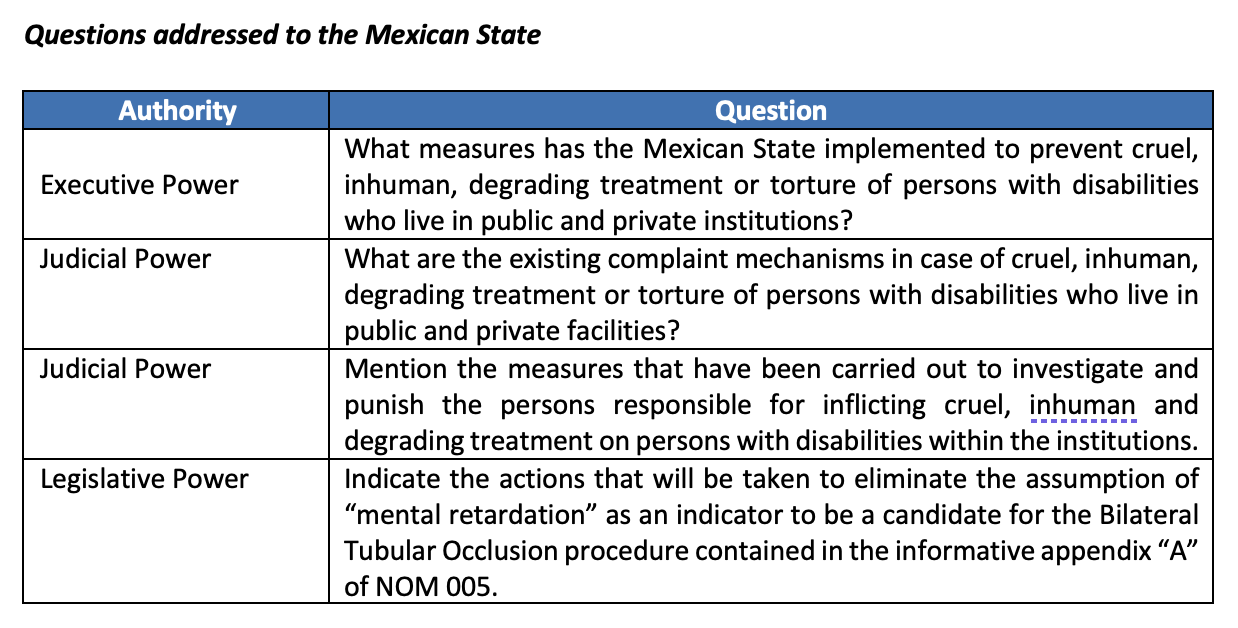

Article 15. Freedom from torture or cruel, inhuman or degrading treatment or punishment

The CRPD establishes that “no one shall be subjected to torture or to cruel, inhuman or degrading treatment or punishment.”[39] However, in institutions DRI has documented the use isolation rooms, physical restraints, physical and sexual abuse, and unhygienic conditions that threaten the health and life of children and adults with disabilities. In institutions, DRI saw children tied down with bandages, some of them fully wrapped in them like mummies, others were put in in cages. Adults spoke about the physical and sexual abuse they’ve endured in institutions, particularly women, who are sterilized to conceal rape at the facilities. Forced sterilization of women has also been documented by the "Colectivo Chuhcán", DRI and “GIRE”. Conditions are so unhygienic in some of these institutions that they directly threaten the life of the people there detained, as they expose them to infections and diseases.

a. Forced Sterilization

In 2014, the CRPD Committee in its Concluding Observations expressed its concern because “persons with disabilities are being sterilized without their free and informed consent in institutions such as “Casa Hogar Esperanza,” where according to reports received by the Committee, forced or coerced sterilization is recommended to, authorized or performed on girls, adolescents and women with disabilities.” [40]

Forced sterilization is only typified in the Federal Criminal Code and the Criminal Codes of 18 States.[41] The National Standard NOM-005-SSA2-1993 “On family planning services” (NOM 005) states that “mental retardation” is an indicator for the permanent contraceptive method called “Bilateral Tubal Occlusion.” Stating that intellectual disabilities are an ‘indicator’ for sterilization assumes that women with disabilities should not reproduce, which is clearly contrary to the CRPD.

In the DRI and Colectivo Chuhcán report "Abuse and Denial of Sexual and Reproductive Rights of Women with Psychosocial Disabilities in Mexico,”[42] 50 women with disabilities were interviewed. One in two women reported that “a family member or a medical staff has recommended to be sterilized.”[43] 42 percent of the women interviewed responded that they had been sterilized[44] in a forced or coercive manner.

In 2017, DRI visited “Centro el Recobro” in Mexico City, a private institution that had 176 women with disabilities. The person in charge of the institution told DRI that: “if they arrive pregnant and they are out of control, when they give birth they are sterilized.”[45] The person in charge of “Centro el Recobro” mentioned to the DRI team that some of the women are already sterilized when the DIF sends them to the institution.[46] Use of isolation rooms

The use of isolation rooms for people with disabilities in institutions continues to be a systemic problem. In several institutions that DRI visited we found people isolated in rooms, cages and patios. For instance, in Baja California’s Psychiatric institution, in Mexicali, DRI found 10 isolation rooms, five for men and five for women. Seven of them were occupied. The director stated that the people can go in and out these rooms but DRI observed that they were locked and the people who were in them had to ask permission to go out. A nurse told DRI that people could stay there “usually three to five days, if they are in very bad conditions, weeks.”[47]

In this institution DRI found a man with an intellectual disability who was approximately 68 years old. According to staff, he had been in an isolation room for about four months. One nurse told DRI that the reason he is in that isolation room is because he started ‘eating dirt and paper sheets.’ The director added that the patient bothers other patients. The nurse told DRI that the patient is permanently in this room “for his own protection.”

At “Casa Hogar San Pablo” in the State of Queretaro, DRI investigators found seven isolation rooms where they daily put children and adults with physical disabilities. Each room measures approximately 1.75 by 1.20 meters.

At the “Centro de Rehabilitación Fortalécete en Cristo” DRI found two people with disabilities locked in a "detox" room, a room with empty walls and a smell of urine and feces. According to the director of this institution, people are placed in this room for several days while they “detox”. However, people with disabilities were not “detoxing”, they were simply locked there for no apparent reason.

The National Mental Health Council (“CONSAME” for its acronym in Spanish) monitored 14 psychiatric hospitals in the country, from 2013 to 2016, and reported that 11 of them use some kind of isolation, either in isolation courtyards, within their own wards for long periods of time, or specifically in isolation rooms.[48] In 2014 and 2015, the “CONSAME” reported that the Yucatan Psychiatric Hospital used isolation rooms for people who are in the institution[49]. According to the reports, in 2014 “an isolation patio was found whose door was closed with bandages and in which there were two isolated users,”[50] as well as “17 isolated people in their wards.”[51] For 2015, the “CONSAME” reported that the people who were in the institution were isolated permanently because they shared the facility with the forensic patients[52] –people who had committed a crime and were deemed to have a psychiatric disability.

b. Physical restraints

In Its concluding observations to Mexico, the CRPD Committee found alarming the use of physical coercion[53] towards persons with disabilities who are living in institutions, and found that it may even amount to “acts of torture or cruel, inhuman or degrading treatment.”[54] The Committee recommended to Mexico “abolish the use of physical restraints and isolation in institutions for persons with disabilities.”[55]

In institutions monitored by DRI, the use of prolonged restraints on minors and adults with disabilities was common. These restraints varied and consisted on wrapping children with bandages fully covering their bodies, using duct tape and clothing. For instance, in the visit to “Hogares de la Caridad” in Jalisco, DRI found a 17-year-old wrapped in a blanket by the torso and tied with duct tape. The young man spends long periods of time tied this way, on a bed with tall wooden bars.

At “Casa Esperanza”, an extremely abusive institution that DRI reported on for Mexico’s evaluation for 2014,[56] DRI found children and adults with their hands and feet tied in painful positions with duct tape and using their own clothing. They were tied with duct tape and bandages, for prolonged periods of time.[57] We are aware that at least one person died while tied up and locked in one of the bathrooms, which was used as an isolation room.[58]

DRI interviewed a person who was hospitalized at the Psychiatric Hospital “Dr. Rafael Serrano” (known as "El Batan") in Puebla. This person mentioned that physical restraints are part of the hospital admission policy. Regardless of the condition in which the users arrive, “the patients are tied up for a whole day.”[59] He mentioned that the nurses ask for help from patients who were more stable to tie the new patients.[60] In the same way, restraints are used as a form of punishment. If a person is considered to be “misbehaving,” they tie him/her up. If a person does not eat “well,” they tie him/her up, too. This person mentioned: in one occasion, they tied me up for reading a magazine out loud because the doctors thought I was hallucinating.”[61]

Mexican laws also allow physical restraints. The Yucatan Mental Health Law allows the use of physical restraints in users.[62] Juan E. Méndez, a UN former Special Rapporteur on torture and other cruel, inhuman or degrading treatment has stated that “restraint on people [with mental disabilities] for even a short period of time may constitute torture and ill-treatment.”[63]

c. Sexual Abuse

Children and adults with disabilities in institutions are subjected to sexual abuse and rape. In “Casa Esperanza”, a case reported to the CRPD Committee in 2014, five women testified that they had been sexually abused in the institution. The response of the State to the serious violations suffered by the victims has been simply to transfer them to other facilities. One of the victims reported having been raped for a period of more than eight months by one of the staff members of the new institution to which she had been transferred.[64]

“Ciudad de los Niños” was another extremely abusive institution where children were raped and possibly trafficked for over four decades in the State of Guanajuato. A local Judge, Judge Karla Macías, determined that the children of “Ciudad de los Niños” had been victims of rape. Her judgement includes the case of a 10-year-old girl who said “suffered touching of a sexual nature by an adult named * and that they played “the father and the mother.” [65] The girl explained how she played dad and mom, “the girl by signs, with her arms flexed, brings them closer to her body at the height of her hips, back and forth, repeatedly, and moves her pelvis forward and backwards.”[66]

d. Inadequate use of electroconvulsive therapies

“Juan had a dispute with the director of the Tabasco Psychiatric hospital and, as a punishment the director ordered that he underwent 16 sessions of electroshock without anesthesia. However, at the eleventh session, the assistant director of the hospital saw him in a very serious condition and, thinking that he could die, ordered the suspension of the procedure. Juan said he ended “like a rag” after the electroshocks. Mr. Juan says he does not remember anything - a side effect of electroshocks - and still has serious sequelae, including temporary memory loss. Mr. Juan also mentions that, due to his condition, he spent two months locked up in his ward, and his friends were the ones who bathed and cared for him.”

Testimony of Juan, detained at the Mental Health Hospital of Tabasco, 2016.

The CONSAME evaluated the Mental Health Hospital of Villahermosa, Tabasco, in 2014 and found that “when electroconvulsive therapy is carried out, the protocol of the hospital is not complied with and seems to be an indiscriminate practice, on average 6 therapies are applied daily.”[67] In 2015, the CONSAME, in one of their monitoring reports reported that “in the ECT logbook it was observed that an average of 10 sessions of electroconvulsive therapy were applied on average; 38 electro-shock sessions were applied to only one user.”[68] The ex-rapporteur against torture, Juan Méndez, pointed out that:

“Unmodified therapy can cause severe pain and suffering and often have consequences [...]. It cannot be considered an acceptable medical practice and can constitute torture and ill-treatment.” [69] Lobotomies

The WHO states that legislation should prohibit “irreversible interventions as a form of treatment on children, especially psychosurgery.”[70] However, the current Yucatan Mental Health Law allows surgical intervention in children.[71] Lobotomies are still carried out across Mexico:

“The IMSS [Mexican Institute of Social Security] provided information regarding lobotomy procedures performed by its hospitals […] from 2010 to 2016. Of a total of 51 cases, 28 were women and 22 men –aged between 1 and 85 years old, with an increasing trend in 2015 and 2016, mainly in the State of Sonora.”[72] In Hospitals of the Institute of Security and Social Services of State Workers (ISSSTE), [73] “from 2004 to 2016, a total of 29 lobotomies were performed [...]. It is striking that, on two occasions, 2 women underwent 2 lobotomies each.” [74]

Although the authorities are unaware of the diagnoses behind the lobotomies[75], it stated that:

“At least 9 of these procedures were performed on women, under a diagnosis of anorexia, and 4 cases (2 women and 2 men) were performed to treat schizophrenia and aggressiveness […] and that at least one of those cases had an unfavorable outcome.”[76]

e. Unhygienic and dangerous conditions

In the institutions that DRI visited, it found inhuman and degrading conditions. The Assistance and Social Integration Center “(CAIS) Villa Mujeres” is a public institution that has an approximate population of 400 women with and without disabilities. One of the women with disabilities who are detained there told DRI about the lack of water in the facility, which makes everything remain dirty, particularly the bathrooms. [77] The same person commented that if you need to drink water, it has to be tap water since they do not have drinking water available for them.[78]

A volunteer from “CAIS Cascada” mentioned that, “the floors are full of blood and feces”[79], the women walk around barefoot and when the area is ‘cleaned,’ they throw water on the floor and all this goes to their feet, causing skin infections.[80]

A person interviewed by DRI who was detained in the Psychiatric Hospital “Dr. Rafael Serrano,” mentioned that the hospital does not have cleaning staff and that the facilities are always dirty. The same person mentioned that in one occasion a patient urinated his mattress during the night and the next morning a nurse forced another patient to lie down on the same mattress, asking him only to flip it. [81]

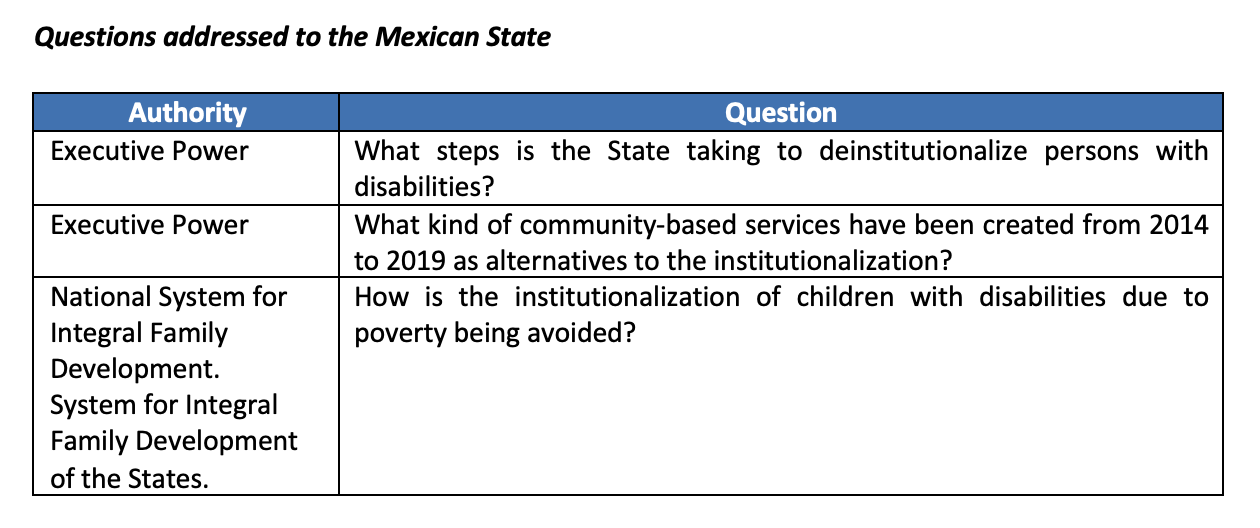

Article 19. Living independently and being included in the community

The Convention recognizes in article 19 the right of persons with disabilities to live independently and be included in the community.[82] In 2014, the CRPD Committee in its Concluding Observations to Mexico expressed its concern about “the lack of a State strategy for the inclusion of persons with disabilities in society and their ability to live independently”[83] and recommended that Mexico “adopt legislative, financial and other measures to ensure that persons with disabilities may live autonomously in the community.”[84]

Mexico continues to enforce a policy of segregation of its most vulnerable populations, especially children and adults with disabilities. Between 2014 and 2019 DRI visited over thirty public and private institutions where children with and without disabilities and adults with disabilities are detained. In these institutions DRI found thousands of children and adults whose rights were being violated by the mere fact that they were segregated from society. These children and adults were also subjected to abuse, inhuman and degrading treatment and torture, as outlined in the previous section.

Mexico has also failed to create and implement a deinstitutionalization strategy. In fact, Mexico continues to invest in institutions. It is estimated that the Ministry of Health allocates about 2% of its budget for mental health and 80% goes to the operation of psychiatric hospitals.[85] According to the Sixth Report of the Government of the Former President Enrique Peña Nieto “from January 2013 to June 2018, 122.7 million pesos (6 million USD) were spent on psychiatric hospitals.”[86] The State of Nuevo Leon foresees an investment of $ 160 million pesos for the creation of a new psychiatric hospital.[87]

Mexico has not created community-based services for persons with disabilities nor has it adopted a deinstitutionalization strategy. None of the 13 State Mental Health Laws contemplate the creation of community-based services for persons with psychosocial disabilities,[88] even though these laws were approved years after the CRPD was signed and ratified by Mexico. DRI is working on an investigation that will include persons with psychosocial disabilities that aims to identify the lack of services in the community in Mexico. This research will be sent to the Committee of the CRPD for the evaluation of Mexico in 2020.

According to the Colectivo Chuhcan, there are no supports for people to be able to live independently and have access to a job with the necessary accommodations.

“Before the disability, I wanted to have my own life project and aspired to an independent life [...] I would have liked to be able to have a job according to my career [chemical pharmacobiology] with the supports that are needed, which are the same as a normal person, but with all the adjustments because, for example, an eight hours job is very hard, perhaps a shift of six hours […] I also aspired to buy a house.”

"If I lived independently, I would like to study [...] demonstrate what I know so that others do not make fun of me.”

“In my case, it is not that I cannot or do not want to be independent, I feel that I would need a person that can give me support.”

“Organizations like the Colectivo [Chuhcán] are needed so people can meet other persons with psychosocial disabilities, to have peer support.”

Testimonies from members of the Colectivo Chuhcán, June 2019.

a. Institutionalization of children

The General Law on the Rights of Children and Adolescents recognizes the right of all children with or without disabilities to live in a family[89] -biological or extended. If the family is not available, children must be placed in a foster family or have the option of adoption.[90] However, according to the Social Assistance Housing Census of the National Institute of Statistics and Geography (INEGI, by its acronym in Spanish) of 2015, there are more than 26,000 children institutionalized.[91] These numbers are below the estimate. In an interview with Ricardo Bucio, Executive Secretary of the National System for the Integral Protection of Children and Adolescents (SIPINNA, by its acronym in Spanish) he mentioned that the number of institutionalized children could be actually 140 thousand. Mexico has no record on how many children with disabilities are institutionalized. In addition, the Mexican State has not created support programs for biological or extended families to eliminate the risk of institutionalization, nor has it created foster families to allow children with and without disabilities to exercise their right to live in a family.[92]

In Mexico, poverty and disability continues to be one of the main factors behind the institutionalization of children. In “Esperanza Viva”, a residential institution in Puebla that houses 92 children, the person in charge told DRI that around “60 percent of the population are here because of poverty.”[93] The facility “Nuestros Pequeños Hermanos,” in Miacatlán, Morelos, that has 500 children, has also admitted that most of its population is in the institution “for poverty reasons.”[94]

Questions addressed to the Mexican State

Authority

Question

Executive Power

What steps is the State taking to deinstitutionalize persons with disabilities?

Executive Power

What kind of community-based services have been created from 2014 to 2019 as alternatives to the institutionalization?

National System for Integral Family Development.

System for Integral Family Development of the States.

How is the institutionalization of children with disabilities due to poverty being avoided?

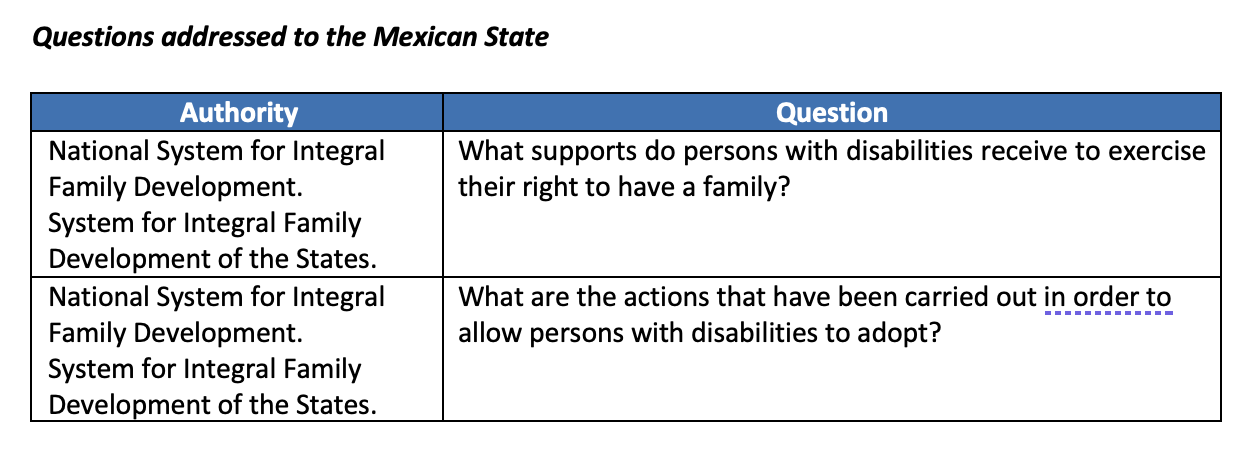

Article 23. Respect for home and the family

The Convention establishes that States Parties “shall take effective and appropriate measures to eliminate discrimination against persons with disabilities in all matters relating to marriage, family, parenthood and relationships, on an equal basis with others”[95]. The report “Abuse and Denial of Sexual and Reproductive Rights of Women with Psychosocial Disabilities in Mexico” found that more than 50% of women have been told that they should not have children. Men and women with disabilities from the “Colectivo Chuhcán” have been told that they cannot be fathers or mothers.

“My mom told me: we do not want you to get pregnant because we cannot support you. We are not going to support you [...]. My sister does not have a disability and they are supporting her with her three children [...]”.

“Once I went to the health center, I went because I had a stomach ache and as soon as they took my blood pressure, the doctor started asking me about my wounds and asked me why I had my wounds [...] I mentioned my [psychosocial] disability , and she started telling me if I knew I could not have children [...] she told me, do not even think about it because you are no good and you cannot and it would be irresponsible and I got really upset about what he said”.

“My sister told me that I cannot have children, that I'm not ready”.

“My brother says that I cannot have children, that I cannot be a father, that I cannot be responsible for a family and I think that is a very big discrimination, because I feel that I have the right as any person to decide if I want or not to have a family and I would like to have a child”.

Testimonies from members of the Colectivo Chuhcán, June 2019.

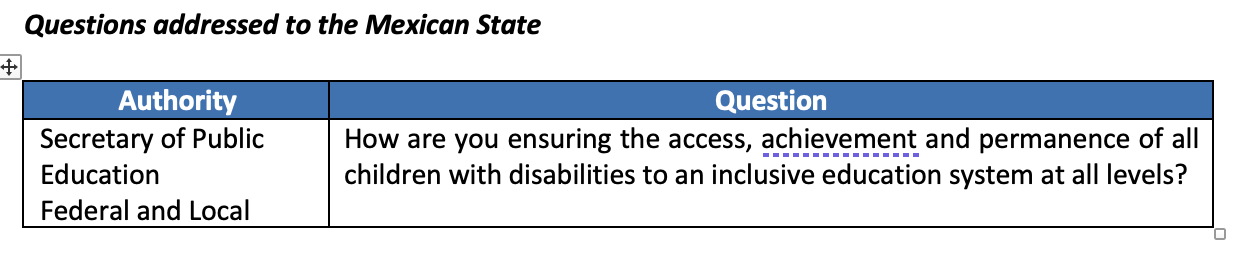

Article 24. Education

The CRPD states that States Parties shall take appropriate measures, including “Ensuring that the education of persons, and in particular children, who are blind, deaf or deafblind, is delivered in the most appropriate languages and modes and means of communication for the individual, and in environments which maximize academic and social development.”[96] The CRPD Committee on the CRC called Mexico to:

“(e) Step up efforts to establish an inclusive education system for all children at all levels, as mandated in the General Act on the Rights of Children and Adolescents, including by providing accessible schools and educational materials, trained teachers and transportation in all areas of the country.” [97]

According to the “ENADID” 2018, a child between 3 and 17 years with a disability is 1.8 times more likely to not attend school, compared to the population without disabilities; 15% of children without disabilities do not attend school compared to 28% of children with disabilities who do not attend school. Something similar happens with illiteracy; 13.8% of children between 5 and 17 years without disability claim not to be able to read or write, while in the population with a disability, it is almost a third of the population who cannot read (31.5%).[98]

Inclusive education is not a reality in Mexico, particularly for children who belong to indigenous populations. DRI visited “Proyecto Paz y Dignidad A.C.” an institution located in Tecate, Baja California. This facility allocates 158 indigenous children in three different ‘houses.’ These children are from an indigenous community that is approximately two hours from Tecate. The main reason why they live in an institution instead of living in their community is due to the lack of educational opportunities in it.

Article 25. Health

The Convention establishes that States Parties “shall take all appropriate measures to ensure access for persons with disabilities to health services” [99] and shall “provide persons with disabilities with the same range, quality and standard of free or affordable health care and programmes as provided to other persons.”[100] In its Concluding Observations, the Committee recommended that Mexico “ensure that women with disabilities may enjoy their right to accessible and safe sexual and reproductive health services, in both urban and rural areas.”[101]

Counseling and contraceptive delivery services have to consider the needs of people with disabilities in order to guarantee their sexual and reproductive rights. “GIRE” has however found that at the federal level, no health institution reported having trained staff on disability issues. At the local level, 91% of the health ministries do not have staff specialized or trained on disability.[102]

The lack of trained staff in health institutions to care for people with disabilities presupposes a lack of support systems that guarantee their rights and respect their autonomy in decision-making on an equal basis with others –including decisions on temporary or permanent contraceptive methods, abortion, or prenatal, partum and postpartum care and, in general, in the exercise of their sexual and reproductive rights.

In October 2018, different organizations participated in the “Global Dialogue on abortion, prenatal tests and disability” and elaborated a document that contains 13 principles to guide their work on these issues.[103] The document foresees, among other issues, that the autonomy and self-determination of persons with disabilities should be promoted with respect to the voluntary termination of pregnancy, as well as the whole spectrum of reproductive justice, especially with regard to transgressions that affect disproportionately women and girls with disabilities, such as forced or coerced abortion, contraception and sterilization. They add that it is necessary to ensure that sexual and reproductive health services are physically and financially accessible and that information and communication on sexual and reproductive health is provided in accessible formats.

“I had a gynecologist at the Psychiatric Hospital “Fray Bernardino Álvarez.” My doctor retired and they told me that they will not see me anymore. Now, I have to pay for it in a private clinic, and I do not think it's fair, because it's expensive. There are no such services in the community available for women with psychosocial disabilities.”

Testimonies from members of the Colectivo Chuhcán, June 2019.

a. Legal and safe abortion

The CESCR Committee examined Mexico, in March 2018. One of the concerns expressed by the Committee is the access of women to abortion differs in relation to the legislation of the State in which they reside, as well as the difficulties that persist in accessing this service under the criminal codes.[104]

Currently, Mexico has a legal framework that allows the voluntary termination of pregnancy in cases of sexual violence. According to the General Law of Victims and the NOM-046-SSA2-2005, family violence, sexual violence and against women, criteria for prevention and care (NOM 046), access to this service must be guaranteed for every woman, with no more requirements than a statement under oath that the pregnancy was a consequence of rape. However, there are still local legislations that establish requirements contrary to the general legislation, as well as other types of barriers that make access to this service in Mexico is precarious or null.[105]

From September 2015 to March 2019, “GIRE” has accompanied three cases of women with intellectual disabilities who, as a result of a rape, became pregnant. In two of the cases, the authorities denied them access to abortion despite the fact that the current legal framework establishes that this service must be guaranteed for every woman, with no other requirements than a declaration under oath that the pregnancy was a consequence of rape. Even though health authorities are obliged to provide emergency care to victims of sexual violence, in the third case that GIRE accompanied, the authority notified the refusal to interrupt the pregnancy 26 days after the request was made.

It is essential that the State guarantees access to these services in accordance with the general regulations without any discrimination, ensuring higher-quality, and more efficient and specialized care for girls and women with disabilities to guarantee the respect for their autonomy at all times.[106]

Article 27. Work and employment

Article 27 of the CRPD states that “persons with disabilities are not held in slavery or in servitude, and are protected, on an equal basis with others, from forced or compulsory labour.” [107] In addition, the Committee recommended Mexico to “set up mechanisms to protect persons with disabilities from all forms of forced labour, exploitation and harassment in the workplace.” [108]

Persons with disabilities are more vulnerable to being victims of forced labour or exploitation in institutions, which constitutes a crime. In the case of the people who were detained at “Casa Esperanza,” multiple testimonies show that the victims were forced to work during their stay in the institution. One woman reported that “in the house I have to wash the dishes. The staff shouts at me. I do not like being here and sometimes I cut myself.”[109] The “Centro el Recobro” in Mexico City has 178 women with disabilities[110]. The women are in charge of the cleaning and caring of women with more severe disabilities.

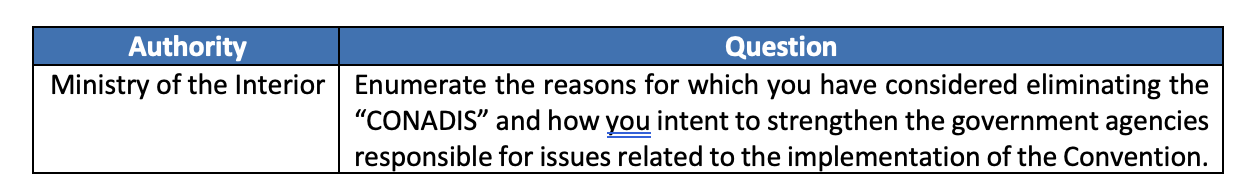

Article 33. National implementation and monitoring

The organizations that are part of this shadow report want to express our concern about the possible disappearance of the National Council for the Development and Inclusion of Persons with Disabilities (“CONADIS”, by its acronym in Spanish). In the course of this presidential administration, no person has been designated to be the head of the National Council. According to the Deputy Secretary for Multilateral Affairs and Human Rights of the Ministry of Foreign Affairs, Martha Delgado, the creation of a National Disability Care System is being considered, however, the structure or functions of this System are not clear yet.

Authority

Question

Ministry of the Interior

Enumerate the reasons for which you have considered eliminating the “CONADIS” and how you intent to strengthen the government agencies responsible for issues related to the implementation of the Convention