Human Rights and Mental Health Uruguay

Mental Disability Rights International

a project of the

Center for Human Rights & Humanitarian Law

Washington College of Law, American University

and the

Bazelon Center for Mental Health Law

Washington, D.C.

June 1995

Acknowledgements

MDRI is indebted to many people in Uruguay who took the time to offer MDRI their observations and insights. To protect their privacy, most of the individuals MDRI interviewed are not named in this report, including many people who use or reside in Uruguay's mental health facilities, members of their families, mental health service providers, members of psychiatric and nursing professional associations, representatives of the Uruguay Ministry of Public Health, the judiciary, and their staff.

MDRI's work in Uruguay would have been impossible without the invitation and assistance of the Instituto de Estudios Legales y Socia/es del Uruguay (IELSUR) and without the close collaboration and invaluable guidance of Francisco Ottonelli, Executive Director of IELSUR, and Sylvia Cousin, a member of IELSUR's Board of Directors. Thanks to the many staff members at IELSUR who arranged all aspects of the MDRI fact-finding mission in Uruguay and offered their open hospitality. Special thanks to Mariana Terra for her long hours of translation and for her warm, thoughtful, and thought provoking introduction to the history, culture, and sights of Uruguay. Christian Courtis, Legislative Aide in the Senate of Argentina, also provided valuable support as a translator and as an active member of the fact-finding mission in Uruguay.

Professor Herman Schwartz, Co-Director of Washington College of Law (WCL) Center for Human Rights and Humanitarian Law provided the support and vision that made the creation of MORI possible and that assured the success of the Uruguay project. Professor Robert Dinerstein of the Washington College of Law provided detailed comments on an early draft of this report. Professor Claire Morel-Seytoux of the University of Monterrey, Mexico, Karen Bower of the Women's Law & Public Policy Program at Georgetown University Law Center, and Melissa Crow, Schell Fellow at Human Rights Watch also contributed valuable comments on the draft. Thanks to Felipe Michelini of the Center for Justice and International Law (CEJIL/Sur), Montevideo, Uruguay, for advising MDRI on this project. Dr. Peter Statsny, Einstein Medical College, reviewed the report and contributed psychiatric references.

Angelica Moncada and Simon Abromovici conducted valuable background research on the mental health law of Uruguay. Peter Hansen helped proof the English text of the report. The report was translated into Spanish by Jerome V. Luhn, Laura Noriega-Martin, Alejandra Segura, and Professor Guillermo Ramirez, Laura Bergman, Valentina Delich, Monique Byrne, and Dr. Luis Byrn. Christian Courtis and Liliana Obregon painstakingly reviewed and prepared the final Spanish translation of the report for publication.

The Washington College of Law Center for Human Rights and Humanitarian Law funded the publication of this report. MDRI's work on the Uruguay project was funded by the Echoing Green Foundation, the Nathan Cummings Foundation, the Bazelon Center for Mental Health Law, and the Washington College of Law Center for Human Rights & Humanitarian Law. Clarence J. Sundram, Leonard S. Rubenstein, and the University of Miami School of Law generously contributed to the cost of travel and research in Uruguay.

Foreword

After centuries of indifference, human rights concerns are now recognized as essential to a free, democratic and humane society, of concern to all decent people everywhere. Because human rights issues arose originally in political contexts, primary emphasis has understandably been given to political rights like speech, press and association. The rights of institutionalized persons were of concern only if they were associated with political abuses.

That has changed somewhat, but the rights of the mentally disabled are still not on advocates' radar screens. Yet, if experience in the United States is any indication, few groups are subjected to as much discrimination, cruelty, and just sheer neglect and indifference. Only pretrial detainees are treated as badly, and as to them, there is at least a suspicion of wrongdoing, despite the presumption of innocence. People with mental disabilities are, however, completely innocent. The only crimes in which they are involved are those that are perpetrated upon them.

Nor is it likely that the United States is unique in this regard. Even in other free democratic societies like Uruguay, where the mental health workers are dedicated to humane treatment of the mentally disabled, this report finds that:

Conditions in Uruguay's psychiatric institutions violate a broad range of rights codified in the [United Nations Principles for the Protection of Persons with Mental Disabilities], including protections against harm and unjustified medica tion, respect for personal dignity, privacy and choice, and the right to treatment directed toward the preservation and enhancement of personal autonomy.

So little attention has been paid to these unlucky people, that despite international treaties, United Nations action, and other well-intentioned initiatives, human rights advocates know little about the treatment of the mentally disabled, and have done even less.

That must change. Those of us concerned about human rights must become aware of the inhumane treatment that even the most civilized societies inflict on the mentally disabled, and start doing something about it. This may be an especially auspicious moment for that, for there is increasing international interest in the treatment of the disabled, as reflected in Article 22 of the Declaration of the United Nations World Conference on Human Rights in Vienna in June 1993, and in the appointment of a U.N. Special Rapporteur on the Equalization of Opportunities for Persons with Disabilities.

This report by the Mental Disability Rights International project of the American University Human Rights Center on the treatment of the mentally disabled in Uruguay is a major step in that direction. It documents the combination of neglect, indifference and outright cruelty that is perpetrated on these helpless people in one country, and it charts a strategy for change that takes into account the economic and social situation in that country. It is indispensable reading for all who are concerned about what has been, until now, a dark corner of human rights abuse. With luck it will be just a beginning.

Professor Herman Schwartz

Executive Summary

This report documents human rights conditions in Uruguay's mental health system and recommends steps necessary to bring the system into conformity with internationally recognized human rights standards. The report is the product of a fact-finding mission conducted November 29 - December 8, 1993 by a Mental Disability Rights International (MDRI) team of attorneys and a psychiatrist. The team came to Uruguay at the request of the Instituto de £studios Legales y Socia/es de! Uruguay (IELSUR), a human rights group based in Montevideo, Uruguay.

The identification of human rights violations in this report should not detract from the impressive efforts of the individuals who work in Uruguay's mental health system who have devoted themselves to the care and concerns of people with mental disabilities. Nor should this report undervalue the strengths of Uruguay's mental health system, its great human resources, and the widespread interest in the rights of people with mental disabilities which together hold promise for Uruguay to be a leader in mental health system reform.

A. Structure of Services

The public mental health system of Uruguay relies almost exclusively on large in-patient institutions at the expense of community-based care. There are more than 2,000 people in Uruguay's public psychiatric institutions (from a total population of 3.1 million people) of whom 1,300 to 1,400 live in asylums (known as "Colonias") in remote parts of the country. Most patients in the Colonias remain there for life.

A few impressive public and private community mental health programs exist in Uruguay. Public programs serve fewer than 200 individuals, however, and they cannot accommodate the large numbers of people who need community services. By official accounts, one-half to two-thirds of people in Uruguay's mental health system are "social patients" without any need for psychiatric hospitalization.

Many "social patients" are not mentally ill but are detained in institutions because they happen to be homeless or have no place else to go. People are held in institutions for committing petty crimes, for alcoholism, epilepsy, old age, or mental retardation. Institutional ization of people with retardation in Uruguay's psychiatric facilities is particularly inappropriate and harmful, because these individuals receive no services tailored to their special needs.

Uruguay's medical and social service systems do not accommodate the needs of people with mental disabilities living in the community, creating added stress that leads to further institutionalization. Mental health coverage other than psychotropic medication is not included in mainstream health care. Disability pensions are terminated for people who obtain a job of any kind, even if such employment does not provide subsistence income.

In the mid-1980s, shortly after Uruguay's return to democracy, the Ministry of Public Health brought together a National Commission to study the need for mental health reform. The National Program for Mental Health put forward by the Commission in September 1986 recommended that Uruguay "abandon the hospital" as the primary locus of mental health services and develop community-based services integrated into the national health system. The National Program for Mental Health was adopted by the Ministry of Public Health, but funds were never allocated for its implementation.

Uruguay's near-exclusive reliance on institution-based treatment results in the unjustified, unnecessary, and potentially harmful institutionalization of people capable of safely living and working in the community. The structure of Uruguay's mental health system thus violates internationally accepted medical and human rights standards adopted by the Pan American Health Organization (PAHO) in the Declaration of Caracas, and the United Nations General Assembly in the Principles for the Protection of Persons with Mental Illness (Ml Principles). The detention of "social patients" at the discretion of hospital authorities constitutes arbitrary detention prohibited by the International Covenant on Civil & Political Rights (the ICCPR) and the American Convention on Human Rights (the American Convention). The improper and unjustified hospitalization of individuals capable of living in the community results in decreased social functioning and violates the right to the "highest attainable standard of ... mental health" protected by the International Covenant on Economic, Social, and Cultural Rights (ICESCR).

International law requires that the detention of "social patients" be terminated and community-based alternatives to psychiatric hospitals be established. Resources currently available for mental health care must be re-directed to ensure the enforcement of internationally recognized human rights. Uruguay is under a legal obligation to invest additional resources for mental health system reform, if this is necessary to enforce the full protections of the ICCPR and the American Convention. To bring Uruguay's mental health system into line with internationally accepted human rights standards, MDRI recommends that Uruguay:

A-1 End the detention of "social patients";

A-2 Conduct a system-wide review of all current commitments to psychiatric institutions;

A-3 Create community-based mental health care and other alternatives to psychiatric institutions;

A-4 Create services to allow people with mental retardation to live in the community;

A-5 End disincentives to work in pension benefits;

A-6 Include psychiatric coverage in mainstream health care.

With or without a further legislative mandate, Uruguay's Ministry of Public Health should:

A-7 Take a leadership role in restructuring the mental health system;

A-8 Involve system users and families in reform efforts;

A-9 Publicly present a plan to the legislature for implementing reforms, including a budget and a timetable.

The Ministry of Public Health's plan should estimate both the cost of creating services in the community and the savings that will arise from closing institutions. Uruguay may need to invest additional resources to restructure its mental health system, particularly to create community-based mental health services, and the implementation plan should include a realistic estimate of these new costs.

B. Civil Commitment

The civil commitment law of Uruguay (entitled the "Law of Assistance to Psychopaths") does not provide the minimum substantive or procedural protections required by the MI Principles.

Uruguayan law allows commitment upon medical certification (requiring the consent of an institution director, two physicians, and a relative). There is no requirement that a patient be dangerous or in need of psychiatric treatment. The only criterion for such commitment is a medical finding of "mental illness," a provision that is not enforced, since large portions of the patient population are not mentally ill. Uruguayan law does not provide a right to independent, periodic review of civil commitment, nor does it provide a right to counsel in commitment proceedings, as the MI Principles require.

On its face, the mental health law of Uruguay violates the minimum requirements of the MI Principles and the protections against arbitrary detention in the ICCPR and the American Convention. Thus, Uruguay must:

B-1 Revise the mental health law to include the establishment of proper substantive commitment standards and procedural protections (including a right to independent, periodic review of commitment, and a right to counsel in commitment proceedings) as required by the MI Principles.

C. Conditions in Institutions

For individuals committed to psychiatric institutions, the experience can be destructive rather than helpful. For most patients, psychiatric services do not enhance personal autonomy or support reintegration into the community. Treatment is often inappropriate and unnecessarily dangerous.

Psychiatric treatment in public institutions is almost totally limited to somatic therapies (psychotropic medications and electroconvulsive therapy (ECT)). These treatments are often administered with no medical justification, e.g. on individuals with mental retardation and no psychiatric diagnosis. The absence of complete treatment records, the lack of specific diagnoses, the shortage of professional staff, and the inadequate monitoring of side-effects render the safe and effective use of psychotropic medications impossible for many patients.

Psychiatric institutions provide no psychotherapy and little rehabilitation or vocational training. Only a minority of patients receive case management to assist them in returning to their work, family, and community. Thus, patients sleep or sit by their bedside, wander the halls, or do nothing most of the day. Whatever social and vocational skills they may have had upon entry are generally allowed to deteriorate.

Living conditions are generally not respectful of the dignity and privacy of residents.

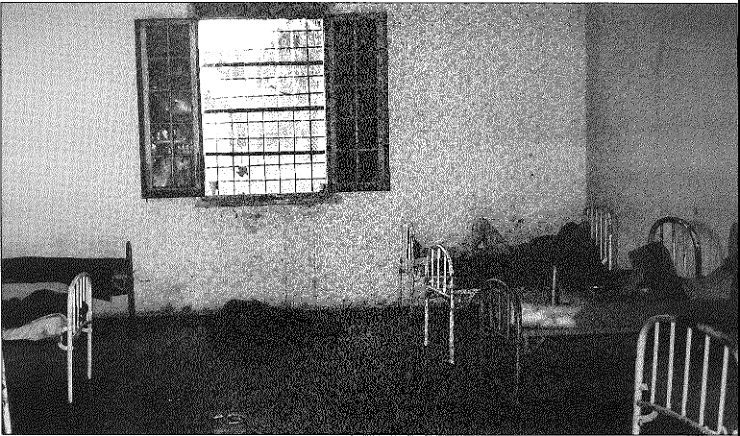

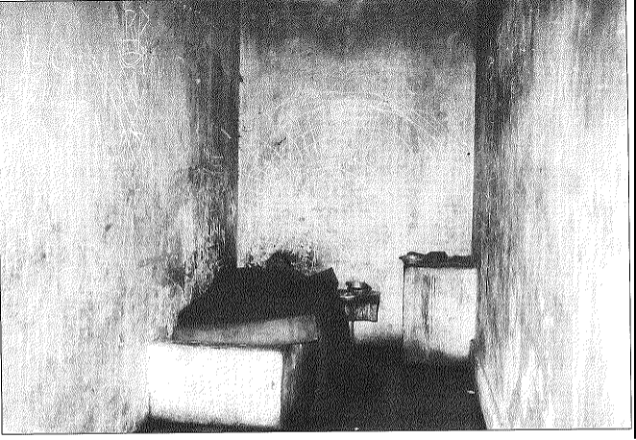

With the exception of a few bed areas where patients have put up a photo or kept a stuffed animal, institutions are almost completely impersonal, undecorated, and drab. Many of the institutions are in old and decrepit buildings, and in some areas the conditions are unhygienic (e.g. the Colonia Etchepare security ward, where clogged toilets flood hallways and where some patients sleep on bare, filthy floors).

There is no system for protecting patients' rights in institutions, and important decisions concerning their rights (including transfer to some locked wards) are made at the discretion of administrators without standards, guidelines, or oversight. Although physical restraints and seclusion appear to be rarely used, there are no established regulations for their use. Some individuals are reported to be held in seclusion for four to six weeks.

Patients are not notified of their rights, and there is a general lack of recognition that they have rights. No complaint mechanisms have been established, nor are there any mechanisms to investigate allegations of abuse or violence.

International pharmaceutical manufacturers are reported to be testing new psychotropic medications in institutions with permission from Uruguayan authorities. MDRI is concerned about potential risks to patients and possible lack of safeguards, including the patients' informed consent, as required by the ICCPR.

Conditions in Uruguay's psychiatric institutions violate a broad range of rights codified in the Ml Principles, including protections against harm and unjustified medication, respect for personal dignity, privacy, and choice, and the right to treatment directed toward the preservation and enhancement of personal autonomy. Improper and dangerous treatment practices and conditions in Uruguay's mental health system unnecessarily and unjustifiably cause great suffering, violating the ICCPR and the American Convention's protections against inhuman treatment. In certain cases, conditions or treatment may be life-threatening, violating the right to life guaranteed by the ICCPR and the American Convention. Conditions leading to the deterioration of mental health and social functioning violate the right to enjoyment of the highest attainable standard of physical and mental health as guaranteed in the ICESCR.

To bring Uruguay's mental health system into conformity with international human rights standards, Uruguay should:

C-1 Adopt treatment standards, including procedures for the proper and safe use of psychotropic medications and ECT;

C-2 Ensure broad-based involvement in development of standards;

C-3 Refer to internationally accepted psychiatric practice guidelines;

C-4 Use internationally accepted diagnoses;

C-5 Improve treatment plans and records;

C-6 Establish a quality assurance system;

C-7 Implement treatment and service programs that build upon existing community supports;

C-8 Conduct a thorough review of current medication and ECT practices;

C-9 Investigate pharmaceutical marketing/research practices;

C-10 Establish continuing education requirements for staff;

C-11 Address problems of staff morale;

C-12 Attack public stigma and the pervasive problem of anomie (despair) in institutions.

D. Oversight

The Ministry of Public Health does not monitor treatment practices at public institutions, and the authorities report that there are no standards by which institutions can be assessed.

The only independent oversight of psychiatric institutions is provided by what is called the "Inspector General of Psychopaths, " a position that was vacant for twenty years. The new Inspector, who took office in October 1993, promised to review every psychiatric commitment in the country. He has only two professional staff members to support him. Patients do not have a right to participate in commitment reviews. Indeed, they may never know about the review, which may be-based solely on a telephone conversation between the Inspector and the institution director.

The government of Uruguay is responsible under international human rights treaties to ensure the safety and well-being of patients detained in mental health facilities. Given the poor conditions in psychiatric facilities, the dangerous treatment practices, and the lack of proper safeguards in the civil commitment process, the existence of independent oversight is particularly important. MDRI recommends that Uruguay engage in a thorough review of treatment practices and:

D-1 Create an effective oversight mechanism to ensure the enforcement of rights in institutions;

D-2 Publicly report on conditions annually;

D-3 Establish human rights committees in psychiatric facilities;

D-4 Support consumer and family advocates.

E. Recommendations to Advocates and the International Community

To create political support for national mental health reform, advocates in Uruguay should:

E-1 Bring together a broad base of constituents for reform including system users, family groups, community providers, mental health professionals, and human rights advocates;

E-2 Re-establish momentum around Uruguay's 1985-86 National Reform Plan which called for the creation of community-based mental health care;

E-3 Educate the public about conditions in institutions and about the existence of alternatives to institutions.

The international community should press for the enforcement of international human rights law:

E-4 The United Nations Special Rapporteur on the Equalization of Opportunities for Persons with Disabilities should evaluate the conditions of people with mental disabilities in Uruguay and Uruguay's efforts to create services and programs that will provide people with mental disabilities the full opportunity to live and work community. The Special Rapporteur should provide technical assistance to Uruguay to create service programs in the community and should help raise international financial support for the development of such programs;

E-5 The United Nations Human Rights Committee should require Uruguay to report on the enforcement of rights of people with mental disabilities under the ICCPR;

E-6 The United Nations Committee on Economic, Social, and Cultural Rights should require Uruguay to report on the enforcement of rights of people with mental disabilities under the ICESCR.

Preface: Goals & Methods of this Report

Mental Disability Rights International (MDRI) sent a fact-finding team to Uruguay in November-December 1993 at the invitation of the Instituto de Estudios Legates y Socia/es del Uruguay (IELSUR), a human rights organization based in Montevideo active in advocating for the rights of people with mental disabilities in Uruguay. Long concerned with human rights violations in the mental health system, IELSUR is initiating a new effort to bring about major reforms in the mental health laws and services in Uruguay.

This report documents human rights conditions in Uruguay's mental health system and recommends steps necessary to bring the system into conformity with internationally recognized human rights standards. This report is the product of a fact-finding mission to Uruguay conducted from November 27 to December 9, 1993 by an inter-disciplinary team of four attorneys and a psychiatrist from the United States and an attorney from Argentina.1 Members of the MDRI team interviewed representatives of the Uruguay Ministry of Public Health, governmental and non-governmental service providers (institution and community program administrators, psychiatrists, social workers, nurses, and other staff), representatives of mental health professional organizations, the President of the Uruguay Supreme Court and attorneys involved in oversight of the psychiatric commitment process. The MDRI team also met with mental health system users and family members. 2

The MDRI fact-finding team conducted site visits at each of two "Colonias" (public psychiatric institutions or asylums located in the countryside), two public psychiatric in-patient facilities in Montevideo, one private psychiatric institution, one institution for boys and adult men with mental retardation and other disabilities, and two community mental health facilities.3 During these visits, team members met with administrators, toured the facility, examined custodial conditions, visited program areas, examined patient charts at random and interviewed system users and staff.

The MDRI team received full access to facilities, patients, and patient records without restrictions. MDRI team members were met with openness and interest by service providers, administrators, representatives of the Ministry of Public Health of Uruguay, members of Uruguay's judiciary, their staff, and all others we interviewed. In addition, representatives of the associations of psychiatric and nursing professions were extremely helpful.

Many of the individuals interviewed by the MDRI team were unsparing in the information and assistance they provided, and they spent a generous amount of their own time with the team, answering questions thoroughly, often with great candor. These individuals provided important insights as to the problems within the mental health system, and they demonstrated a genuine concern for people with mental disabilities. This report would have been impossible without this support.

Three members of the MDRI fact-finding team presented a summary of the report's findngs at a conference organized by IELSUR in Montevideo, Uruguay, August 17 and 18, 1994. Representatives of the Ministry of Public Health, directors and administrators of Uruguay's major public psychiatric institutions, officers of psychiatric and nursing associations, independent service providers, and community leaders (including psychiatric system users and their families) participated in a lively discussion of the report at the conference. Human Rights and Mental Health: Uruguay reflects many of the issues raised at the conference. An advance copy of this report was submitted to the Ministry of Public Health for comment in December 1994. MDRI offered to publish a response by the Ministry of Public Health and offered to wait until March 20, 1995 before going to press. MDRI received no response to our offer.

In individual meetings with government representatives, mental health system administrators, providers, family members, and system users, MDRI team members were encouraged by the widespread support for improving and reforming Uruguay's mental health system. This confluence of interest and concern presents the greatest possible hope for bringing the full protections of human rights law to people with mental disabilities in Uruguay.

This report is not intended to single out Uruguay for criticism but to examine the enforcement of international human rights law that applies to people with mental disabilities universally. The international human rights community should monitor these rights worldwide, and MDRI has begun to do so in South America, Eastern Europe and the United States. The views expressed in this report are those of Mental Disabilities Rights International and the authors and do not represent a position of the Washington College of Law or American University.

I. Introduction

This introduction describes the international human rights standards for the treatment of people with mental disabilities and Uruguay's obligation to reform its mental health system under international human rights law. In addition, the introduction provides background about the historical and political context of Uruguay, including the country's history as an innovator in social welfare programs. Finally, the introduction outlines the organization of Uruguay's present mental health care system.

A. Mental Disability Rights: An International Concern

In the latter half of the twentieth century, there. has been enormous growth in the reach of international human·rights law and its application to people especially vulnerable to abuse. The United Nations has drafted international human rights treaties to protect the rights of women, children, refugees, and ethnic or national minorities. In addition, the United Nations General Assembly has adopted human rights resolutions which set minimum standards in many areas once considered the exclusive concern of domestic policies, including rights in the context of labor and employment, marriage, education, social welfare, the treatment of prisoners, and the treatment of people with mental disabilities.4

The process of establishing international minimum standards for the treatment of people with mental disabilities began in the early 1970's. In 1971, the United Nations adopted the Declaration on the Rights of Mentally Retarded Persons,' and in 1975 the United Nations adopted the Declaration on the Rights of Disabled Persons.6 In the late 1970's and early 1980's, specialized agencies of the United Nations began to develop human rights standards for people with mental illness.

As the United Nations was drafting human rights standards for people with mental illness, regional bodies, such as the Pan American Health Organization (PAHO) took the lead in calling for nations to take concrete steps to assure the protection of human rights for people with mental disabilities.7 In an historic meeting convened by PAHO in November 1990, the Declaration of Caracas was adopted by legislators, non-governmental organizations (NGOs), mental health professionals, and human rights leaders from North and South America.8 The Declaration found that exclusive reliance on the psychiatric hospital "isolates patients from their natural environment ... generating greater social disability. "9 Such conditions "imperil the human and civil rights of patients. "10

The Declaration of Caracas calls on national authorities and NGO's to restructure mental health care systems to "promote alternative service models that are community-based and integrated into social and health care networks. "11 Mental health resources must be used to "safeguard personal dignity and human and civil rights"12 and "national legislation must be redrafted if necessary ... "13 to ensure the protection of human rights.

In December 1991; the United Nations General Assembly adopted the final draft of the Principles for the Protection of Persons with Mental Illness and the Improvement of Mental Health Care (hereinafter the "Ml Principles").14 The MI Principles are the most detailed and comprehensive codification of mental disability rights under international law.15 They provide an instrument for fair and consistent evaluation of human rights practices in mental health systems around the world, applicable across cultures to all levels of economic development. The MI Principles recognize that certain practices will vary from country to country, and according ly, they protect the right of the patient to "treatment suited to his or her cultural background. "16 At the same time, the United Nations working group that developed the MI Principles made clear that the MI Principles are "minimum . . . standards"17 designed to "adequately reflect and accommodate all legal and social systems and all stages of development without sacrificing the essential needs and basic rights of the individual human beings ultimately concerned."18 Thus, the MI Principles state that each country should "implement these Principles through appropriate legislative, judicial, administrative, educational and other measures "19

The Ml Principles apply broadly to people with mental illness, whether or not they are in psychiatric facilities. In addition, the MI Principles apply to "all persons who are admitted to a mental health facility, "20 whether or not they are diagnosed as mentally ill. The Ml Principles protect all such people against discrimination21 and detail a list of rights intended to ensure that people with mental disabilities and other people in mental health facilities are "treated with humanity and respect for the inherent dignity of the human person. "22

The Ml Principtes set out substantive criteria23 and due process protections24 against improper psychiatric commitment. Among the substantive criteria for commitment to a mental health facility, the Ml Principles limit commitment to people diagnosed as mentally ill "in accordance with internationally accepted medical standards."25

The Ml Principles specify that people in mental health treatment have the right to protection against "harm, including unjustified medication . . . "26 "No treatment shall be given to a patient without his or her informed consent ... " (except under special circumstances set out in the Ml Principles).27

The Ml Principles emphasize throughout that "[e]very patient shall have the right to be treated in the least restrictive environment ...."28 Within psychiatric facilities, "[t]he treatment of every patient shall be directed towards preserving and enhancing patient autonomy. "29 In addition, the Ml Principles state that "[e]very patient shall have the right to be treated and cared for, as far as possible, in the community in which he or she lives. "30

Many of the rights in the MI Principles create protections against governmental intrusion upon the lives of people with mental disabilities, while other rights require countries to provide appropriate mental health services.31 Thus, the MI Principles are intended to provide a full range of human rights protections to people with mental disabilities, allowing them the opportunity to enjoy the same freedoms and rights as other people and to live life to its fullest potential.

Since the adoption of the MI Principles, the United Nations has continued to press for the advancement of domestic and international efforts to improve conditions and opportunities for people with mental disabilities. In December, 1993, the General Assembly adopted the Standard Rules on the Equalization of Opportunities for Persons with Disabilities (the "Rules on Equalization").32 In the Rules on Equalization, the United Nations specifies that states should devise policies, 33 develop rehabilitation and other service programs, and reform laws "to create the legal bases for measures to achieve the objectives of full participation and equality for persons with disabilities. "34 To the extent that such programs and legal protections require the investment of resources, "States have the financial responsibility for national programmes and measures to create equal opportunities for persons with disabilities. "35

The Rules on Equalization propose that States "at regular intervals, collect . . . information concerning the living conditions of people with disabilities"36 and create "national coordinating committees, or similar bodies, to serve as a national focal point on disability matters. ,m The Rules on Equalization also call for "international cooperation concerning policies for the equalization of opportunities for people with disabilities."38 Finally, the Rules on Equalization create a Special Rapporteur to monitor implementation of the Rules and to initiate international exchange and cooperation on the improvement of conditions for people with disabilities. 39

B. Uruguay's International Treaty Obligations

The Ml Principles elaborate upon certain protections that are guaranteed by international human rights treaties, to which Uruguay is a party, including the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights (ICCPR),40 the International Covenant on Economic, Social, and Cultural Rights (ICESCR),41 and the American Convention on Human Rights (American Convention).42 As such, the Ml Principles can be used as a guide to application of human rights treaty provisions to conditions in mental health systems.43. The protections in the Ml Principles relating to civil commitment to a psychiatric institution, for example, protect against "arbitrary detention," as prohibited by the ICCPR44 and the American Convention.45 Practices in mental health facilities which violate the MI Principles and cause great suffering may constitute "inhuman treatment" prohibited by these treaties46 or may violate the right of detained persons to be "treated with humanity and with respect for the inherent dignity of the human person."47

The ICCPR and the American conventions create a legal obligation on State Parties to "respect" and "ensure" the full enforcement of their protections.48 State Parties undertake to take "legislative or other measures as may be necessary to give effect to the rights recognized in the present Covenant. "49 The ICCPR makes no exception to the duty of full enforcement for rights that may require the investment of resources, and rights may be limited ("derogated") only "[i]n time of public emergency which threatens the life of the nation and the existence of which is officially proclaimed. "50

Uruguay is also urrder an obligation to ensure the "highest attainable standard of physical and mental health" under the ICESCR.51 Countries can work toward this treaty obligation by establishing mental health policies consistent with the minimum standards established by the MI Principles. For example, policies consistent with the principle that "the treatment of every patient shall be directed toward preserving and enhancing patient autonomy"52 or the principle that "[e]very patient shall have the right to be treated and cared for, as far as possible, in the community ... "53 can be considered a step toward the enforcement of the treaty obligation to ensure the highest attainable standard of mental health.

Unlike ICCPR, which creates an immediate duty of full enforcement, the ICESCR creates a duty of "progressive enforcement." No country can produce the "highest attainable" standard of mental health overnight, but each Party to the ICESCR "undertakes to take steps ... to the maximum of its available resources, with a view to achieving progressively the full realization of the rights" established under the Covenant.54 Even though outcomes may only be achieved over time, "the obligation 'to take steps' is an immediate one .... At minimum, this might involve the drawing up of a detailed plan of action for the progressive enforcement of the right. "55 The steps taken should be "deliberate, concrete and targeted" to the full enforcement of rights.56

The ICESCR's requirement that a State take steps "to the maximum of its available resources" does not specify which of its national resources can be considered "available" for reform.57 At minimum, State Parties to the ICESCR must use resources currently available in mental health budgets to enforce policies that will uphold the rights established in the ICESCR. Even where resources are limited, the obligation to "devise strategies and programmes" for the promotion of rights established in the ICESCR "are not in any way eliminated as a result of resource constraints. "58

As this report demonstrates, improper treatment practices in Uruguay's mental health system raise fundamental human rights concerns. Yet the identification of human rights violations is not meant to suggest that the individuals working within Uruguay's mental health system intend to cause danger or suffering.59 On the contrary, MORI encountered a large number of staff dedicated to the well-being of people in their care. The reforms proposed in this reort are necessary so that same staff dedication can be properly re-directed toward treatment that is appropriately respectful of the rights of people with mental disabilities.

C. Political & Historical Context of Uruguay

Uruguay is a small country of approximately three million people located on the Atlantic coast of South America between Argentina and Brazil. Uruguay's per capita gross domestic product is the forty-fifth largest in the world (on approximately the same level as Hungary and Greece), but it is ranked twenty-ninth according to the "Human Development Index" of the United Nations Development Program (UNDP).60 The UNDP ranking reflects the fact that Uruguay has a high rate of literacy,61 an excellent system of higher education,62 a long life expectancy, and many good social welfare programs. Although social programs have been cut back in recent years, the distribution of income in Uruguay is still the most egalitarian in Latin America.63

1. Welfare state, dictatorship and democracy

From the late nineteenth century to the mid-twentieth century, Uruguay enjoyed a long period of economic growth and political stability. During this time, Uruguay developed some of the best and most innovative social welfare programs in the region. A period of economic decline began in the 1950's and continued into the 1960's. In 1973 the military took power.

The military held power for twelve years in what was a brutally repressive regime.64 After a 1980 plebiscite in which the military government was surprised by a vote against a constitution that would have legitimized its power, the military allowed general elections. On March 1, 1985 the military government stepped down and the winner of the election, Julio Marfa Sanguinetti of the Colorado party, was allowed to take office.

2. Impact of economic decline and dictatorship

Uruguay's formidable array of public benefits began to decline in the 1960's as the economy faltered, and social programs were further cut back during the dictatorship. Hospital administrators and representatives of the Ministry of Public Health reported to MORI that the dictatorship caused a period of stagnation in the mental health system when major reforms were impossible. When the military came to power in 1973, the worldwide move toward treatment of people with mental disabilities in the community had just begun to influence thinking about mental health service planning in Uruguay. After the coup, innovation became difficult or impossible. The result was the maintenance of the status quo - reliance on large, custodial hospitals for the treatment of most people with mental disabilities. Few, if any, community alternatives to large psychiatric hospitals were developed in the 1970's and 1980s.

3. National Program for Mental Health

Shortly after the re-establishment of democracy, there were efforts to restore and improve social programs that had been allowed to languish during the dictatorship.65 The Ministry of Public Health initiated a new effort to study and plan comprehensive reform of the mental health system. 66 The Ministry of Public Health established an inter-disciplinary commission of thirty six representatives of all sectors of the mental health system (the "National Commission") , which produced a program for national reform, the Programa Nacional de Salud Mental (the "National Program"). 67 The National Program proposed two main goals for reform: (1) the development of a community-based mental health system integrated within the general health care system and (2) the establishment of a campaign on prevention and rehabilitation. The plan emphasized the importance of an inter-disciplinary approach to mental health treatment in which families would be integrally involved in prevention and rehabilitation. When it was completed in 1986, the National Program was approved by the Ministry of Public Health, and its goals are the official policy of the Ministry today.

Psychiatrists, social workers, and nurses interviewed by MDRI reported that, following the adoption of the National Program in 1986, there was a widespread feeling of hope that major changes would take place in the mental health system as a result of the National Program. As of 1993 when the MDRI team visited Uruguay, however, the National Program had not been implemented. Neither the National Commission nor the Ministry of Public Health ever calculated the cost of implementation,68 and the legislature never appropriated the necessary funds. Despite this, Ministry of Health Officials report that some elements of the National Program have been put into effect. As recommended in the National Program, there was a move toward the decentralization of mental health services, with mental health units having been established in public hospitals outside of Montevideo. A mental health unit was established in Maciel Hospital in Montevideo to be the first receiving hospital before patients were transferred to other hospitals. In addition, the Ministry of Health and administrators at the Colonias engaged in significant efforts to address life-threatening conditions at the Colonias, such as insufficient food and heat.

In recent years, as Uruguay's economy stagnated, the Ministry of Public Health has been subject to budget cutbacks, leaving the mental health system even further from the goals set forth in the National Program for reform.69

D. Organization of Uruguay's Mental Health System

There are both private and public mental health services in Uruguay. Sixty percent of the population receives health care (including access to mental health care) through "mutualistas,"70 networks of private hospitals and physicians that provide services under governmentally mandated insurance plans. Most working people in Uruguay are required to become a member of a mutualista. Thirty percent of the population who have not paid to be part of the mutualista system may receive services through the public health care system. Additional private services also exist, serving wealthier individuals and government employees.71

1. Mutualistas

Limited outpatient and inpatient mental health care is available through mutualista hospitals, consisting almost entirely of pharmacological treatment. No patient management, vocational programming, rehabilitation, or psychotherapy is available through mutualistas.

Outpatient care is provided by psychiatrists at mutualista hospitals and "policlinicas" (outpatient clinics). Outpatient care consists of very brief visits with psychiatrists (usually 10-15 minutes) for the purpose of prescribing medications and monitoring blood levels of medications. The mutualista will pay for the cost of inpatient care at a private, mental health facility for up to thirty days. Such facilities often do not provide any psychiatric treatment programs themselves, so mutualista psychiatrists will visit patients in these facilities to oversee the prescription of psychotropic medications and the administration of ECT. Private inpatient mental health facilities do not exist outside the capital, Montevideo. Thus, all private inpatient care outside Montevideo is provided through mutualista general hospitals.

2. Public hospitals

The public mental health care system services individuals who have no other form of insurance and cannot provide for their own private care. It also provides for long-term patients who have used up benefits provided through the mutualista system.

The public mental health system consists almost entirely of inpatient facilities, with some treatment to outpatients. There are just over 2,000 inpatient psychiatric beds in the country (.06% of the three million people in Uruguay).72 According to the Ministry of Public Health, the cost of care to the government is twenty to twenty-five dollars per day for each inpatient psychiatric bed.

Public inpatient beds in Uruguay are divided between two "Colonias" (Santin Carlos Rossi and Etchepare) located ninety kilometers outside of Montevideo, housing a total population of just above 1,300, and two psychiatric institutions in Montevideo, Musto and Vilardebo, with populations of 600 to 650, respectively.

According to Ministry of Public Health officials, the average length of stay in the Colonias is at least ten years. At Musto and Vilardebo, the Ministry of Public Health reports that the average length of stay is approximately one year. The MDRI team was not able to verify these figures, but there is evidence to suggest that the average length of stay at each of these institutions may be much longer.73

There are no public, inpatient services for the treatment of alcohol or substance abuse.

Protective shelters for people who are homeless are not available.

3. Disability pensions

A pension system for people unable to work due to mental disabilities is available through the social security system. Only individuals who have worked and paid into a social security system are eligible for this pension, equivalent to eighty to one hundred dollars per month.

To qualify for disability, individuals must demonstrate that they .are unable to work. Thus, if a person on disability gets any form of paid work, he or she loses disability payments entirely (regardless of whether the individual's total earning are sufficient to live on). Recipients of disability benefits, family members, and social workers complained that this rule is a disincentive to find jobs. Since the pension is not enough to live on, patients living in the community are reported to work "off the books." This practice makes it difficult to find jobs and results in individuals working without any legal protections or benefits.

4. Professional resources

Uruguay is rich in human resources and has a well educated population. The country has a plentiful supply of psychiatrists and psychologists, but there is a great shortage of professionals with more basic and widely applicable skills - such as psychiatric nurses and psychiatric social workers.

There are more than 450 psychiatrists registered with the Uruguay Psychiatric Association,74 a relatively high concentration of psychiatrists per capita by world standards.75 Most psychiatrists are trained in the country at the University of Uruguay medical school. There are approximately 2,500 psychologists in Uruguay with a five-year college degree.76 Most psychologists are psychoanalytically trained and take patients in private practice.

There are a large number of trained psychiatrists and psychologists currently working in private practice in Uruguay who could potentially contribute an enormous amount to the mental health system. There are also many low-paid mental health professionals and non-professionals who could contribute much more than they now do, but who can only afford to work part of the time in the public mental health system. Within each institution, MDRI found a core of the staff who demonstrate great commitment to their work and to the well-being, dignity, and rights of patients. These individuals, many of whom work at other jobs, work very long hours on behalf of patients in public facilities.

There is a great potential for new opportunities for mental health professionals to contribute to the improvement of services. More and better mental health professionals could be attracted to working in the public sphere, and individuals now working in the public mental health system might contribute more as they saw their efforts come to fruition.

There is a great shortage of other professionally trained staff. Because of low pay in the public mental health system, public hospitals are generally not able to hire sufficient numbers of specialized nurses and social workers.

According to representatives of the Association of Nurses of Uruguay, there are 1,800 university trained nurses in Uruguay, but very few work in public psychiatric institutions because of the low pay. There is reported to be a great shortage of trained psychiatric social workers in the country, and only a few work in public psychiatric facilities.77 The great majority of staff, known as "tecnicos," are non-professionals with only in-service training.

5. Services for victims of human rights abuses

The Servicio de Rehabilitacion Social (SERSOC) is a non-governmental organization established to provide mental health care to individuals and families suffering from the post traumatic effects of torture, disappearances, and other abuses under the dictatorship. Psychologists, social workers, psychiatrists and other physicians volunteering their time and working at low pay for this organization have helped more than 3,000 clients. SERSOC estimates that they have been able to serve only a small portion of the population who have experienced severe mental health problems as a direct or indirect result of abuse. Despite this, the organization receives no support from the public or private mental health care systems.

II. Human Rights Conditions

The primary findings of MDRI's investigation of human rights conditions in Uruguay's public mental health system are described below. Section A describes the structure of Uruguay's mental health system and the human rights implications of a system based almost exclusively on in-patient treatment. Section B describes Uruguay's civil commitment law, its implementation, and analyzes the extent to which it comports with international standards. Section C describes conditions in Uruguay's psychiatric facilities and identifies practices that violate international human rights standards,78 and Section D analyzes the extent to which oversight mechanisms exist to ensure the enforcement of international human rights in the mental health system.

A. Structure of Public Services

Medical and human rights standards adopted by the Pan American Health Organization (PAHO) in the Declaration of Caracas and the United Nations General Assembly in the Ml Principles call for governments to structure service systems to ensure support for people with mental disabilities in the community.79 As the Ml Principles provide, "[e]very person with a mental illness shall have the right to live and work, as far as possible, in the community. "80 In addition, every patient has the right "to be treated in the least restrictive environment. "81

One of the most noticeable aspects of Uruguay's mental health system is that it relies almost entirely on psychiatric institutions. This near-exclusive reliance on institution-based treatment results in the unjustified, unnecessary, and potentially harmful institutionalization of people capable of safely living and working in the community.

The segregation of patients in hospitals often breaks down personal, family, and economic ties to the outside world and results in a decline in social and mental health functioning. The Ministry of Public Health, psychiatrists, nurses and others noted their concern to MDRI with regard to the imbalance of services, and they have attempted to remedy this situation. There are a number of impressive community mental health programs in Uruguay.82 These programs provide essential services that allow a small number of individuals to leave institutions and receive mental health care in the community. Such programs serve as an Uruguayan model for mental health services which allow people to receive support and treatment in their own communities.

1. Custodial institutionalization

Uruguay's mental health institutions have two functions, acute care and long-term care. Long-term patients receive essentially custodial care, which includes psychotropic medication and a limited number of in-hospital activity programs. Staff at the Colonias informed MORI that the primary emphasis of care is on maintaining individuals within institutions rather than providing rehabilitation and returning individuals as quickly as possible to the community from which they have come.

The lack of emphasis or urgency placed on rehabilitation and reintegration into the community can be seen·throughout Uruguay's public mental health facilities. The problem of custodial institutionalization is particularly extreme for at least half of the 2,000 individuals in the public system who are labelled "chronic patients" and are thought to have little or no potential for return to the community. Indeed, "chronic patients" live ten, twenty, thirty years or their whole lives in the psychiatric facility. Many "chronic patients" receive no rehabilitation programming that might give them the hope of ever leaving the institution. Most residents of the Colonias are reported to live there until they die.

Custodial hospitalization adversely affects other patients who only need acute care. Overcrowding makes it difficult to find beds for some acute patients. By stretching the already inadequate rehabilitation and out-placement services at institutions (described in Section C below), "short term" stays in the institution last for unnecessarily long periods of time. At Musto, a facility designed as an acute care facility, the average length of stay is reported to be one year (the average length of stay at Musto may well be much longer, however, given the large number of long-term patients).

2. "Social patients"

Authorities at Uruguay's public psychiatric institutions reported to MORI that between one-third and two-thirds of the 2,000 inpatients have no need to be committed to a psychiatric institution but are held there because they have no place else to go. These individuals are commonly known as "social patients." According to institution authorities, all of these individuals could be moved out of institutions if appropriate community facilities were available.

Officials and mental health system administrators expressed great concern about "social patients," and they observed that the dislocation of these individuals stems from problems that go far beyond the mental health system. Indeed, the mental health system is forced to cope with the effects of a range of social problems - including poverty, unemployment, the lack of affordable housing, and the breakdown of family support systems - that are not necessarily linked to mental health. These social problems cannot be solved alone by Ministry of Public Health officials or institution administrators.

The ranks of the social patients include four categories of individuals:

(1) People who may once have needed hospitalization

The first category of social patients are individuals with mental illness who may once have required psychiatric hospitalization but who could now live safely in the community with appropriate community treatment. This includes "short-term" or "acute" patients, who are likely to leave the institution eventually, as well as "chronic" patients who may only leave the institution after many years. For both populations, the unnecessary length of their stay increases the difficulty of returning to the community as family and economic ties to the community are weakened and lost.

At Colonia Rossi and Colonia Etchepare, there is a particularly large number of long term "chronic" patients who have lost almost all contact with the outside world. Many of these individuals are elderly and neither need nor receive any form of psychiatric treatment but may require nursing care.

(2) People with other disabilities or illnesses and elders

The second category of social patients may have no mental illness but have another disability or illness for which they may require community support, such as mental retardation, epilepsy, or alcoholism. In the Colonias, one-third to one-half or more of all residents may have mental retardation.83 All these individuals could function in the community,84 but specialized services suited to their needs are lacking. Psychiatric institutionalization is particularly inappropriate for people with mental retardation, because these individuals are particularly vulnerable to abuse and neglect. In Uruguay's psychiatric institutions, no habilitation services are provided to meet their special needs; instead, they often receive psychotropic medications or ECT that may be inappropriate to their needs.

In institutions, MORI also found elders who lack family or who are unable to take care of themselves. MORI documented the case of an elderly woman who lived by herself with many cats and other pets. When neighbors complained to the police about the sounds and smells of the pets, the woman was placed in a psychiatric hospital. Upon arrival at the institution, psychiatrists determined that the woman was not mentally ill, but she was held there because no other placement could be found for her. Unlike many other social patients, this woman was eventually able to leave the institution because a placement was identified for her in a nursing home.

(3) Petty criminals, social outcasts

A portion of social patients without mental illness are detained in institutions by judicial order. Among the people in this category are petty criminals who may also be alcoholic or mildly mentally retarded, or may simply display bizarre behavior of one form or another that leads judges to refer them to psychiatric institutions rather than to prisons. As a result of this disposition, however, the individual will be subject to an indefinite period of detention, possibly longer than if convicted of the petty crime for which he or she may have been charged. Mental health officials are unable to release these individuals without a judicial order. This problem is discussed further in section B-4, below.

In one case, MDRI team members interviewed a patient who was reported to be a lesbian. Although thi patient was also mildly mentally retarded and could have been hospitalized as a "social patient" on that ground alone, the fact that she was a lesbian apparently contributed to the difficulty of returning her to the community. Indeed, the director of one institution said that gay and lesbian patients were excluded from one outpatient placement program for fear of antagonizing people in the community.

(4) People who are homeless

A fourth category of institution residents have no mental illness, and may have no other disability, but are homeless or have no other place to go. At Vilardebo Hospital, we interviewed a Brazilian woman who was living in the institution while waiting for official papers to be approved and for financial assistance from her family to come so that she could return home. A sixteen year-old woman at Colonia Etchepare reported to us that she lived in the Colonia because she was born to two patients in the institution.

The institutionalization of people who are homeless is a graphic illustration of the mental health system being assigned a responsibility that has nothing to do with mental health. The government of Uruguay must take responsibility for this problem, which cannot be solved by officials of the mental health system alone.

3. Lack of community-based alternatives

The Ml Principles provide that "[e]very patient shall have the right to be treated and cared for, as far as possible, in the community in which he or she lives. "85 Many people are forced to stay in institutions because there is a great shortage of community-based alternatives. In addition to the 1,400 or so individuals considered to be "social patients" in public hospitals, there is almost certainly a need for community services for individuals in private psychiatric facilities and among individuals currently receiving no mental health treatment. In addition, many other current residents of public psychiatric facilities not labelled "social patients" by the institutions might well prosper in the community if services were available.

The Substitute Family Program, which places former residents of the Colonias with families, is a very impressive model. The program provides payments to families who are willing to take in a former psychiatric patient. Although payments to families are small (the equivalent of approximately thirty-eight dollars per month) there is no shortage of families willing to take in psychiatric patients. The program not only provides a home in the community for former long-term residents of the Colonias, it provides follow-up services that protect the safety and promote the well-being of the former patient, including mental health care and assistance in finding a job. The program also builds upon existing community structures, making contacts for the patient with churches, civic associations, and social welfare programs.

Although organizers report that the substitute family program needs additional funds, it now functions on strikingly small government contributions. The program could be greatly expanded without large increases in funding.

There are also both governmental and non-governmental models for supportive mental health services in the community. The public mental health system currently supports one rehabilitation program in the community, the National Center for Psychiatric Rehabilitation. The National Center provides a setting for psychiatric treatment and rehabilitation of forty to sixty people with mental disabilities, as well as a supported work program for eighty participants. Each program participant is evaluated by an inter-disciplinary team of psychiatrists, psycholo gists, and social workers, and an individual treatment plan is developed. Mental health treatment is discussed with the patient, and no coercive treatment is provided. Participants in the rehabilitation program live on their own or with families and come to the rehabilitation center for a half or full day of crafts, recreation, and occupational therapy.

The National Center for Psychiatric Rehabilitation is the only community facility in the public mental health system. In addition, four or five private community mental health treatment centers also exist. MDRI visited one such facility, the Sur Palermo Rehabilitation Center, which provides structured programs for the rehabilitation of sixteen to twenty former psychiatric patients in a supportive environment. Staff and service users are considered "members" of a co equal community, and no treatment is provided without the user's understanding and consent. Former members and their families reported to MDRI that the Sur Palermo program provides an effective service that helps former psychiatric patients live in the community and avoid re hospitalization.

The two community mental health programs reviewed in this report demonstrate that Uruguay has the technical resources and know-how to develop community facilities, and can do so with a limited infusion of public resources. In addition, they demonstrate the cultural relevance and practical value of programs built on respect for the choice and rights of system users.

In addition to the lack of mental health services in the community, there is also a lack of many other kinds of services that would allow people to leave psychiatric institutions. There is a particularly great need for habilitation and support services for people with mental retardation. Almost every person with mental retardation now living in an institution could function in the community with a great improvement in quality of life.86 Despite this, the MDRI team was not able to locate a single supported living program in Uruguay that would allow adults with mental retardation to function in the community. There are also reported to have been recent cutbacks affecting community programs for people with alcoholism and for homeless shelters.

Finally, the resources available to increase community-based alternatives to institutions that do exist have not been fully tapped. In addition to serving as models for new programs, existing community mental health programs could be expanded with only small increases in government support. The Director of the National Center for Psychiatric Rehabilitation explained that his facility is currently operating under capacity. Without an increase in staff or office facilities, the Center could take another ten or twenty patients. The staff of the substitute family program also explained that there are more families willing to take psychiatric patients at the current rate (approximately thirty-eight dollars per month per patient) than there are currently funds to support. The Sur Palermo and SERSOC programs receive no governmental funding at all.

B. Civil Commitment

Civil commitment to psychiatric institutions in Uruguay is regulated by the law of "Assistance to Psychopaths."87 The law, first enacted in 1936, fails to provide the minimum protections against improper commitment set out in the MI Principles with regard to both substantive criteria and procedural protections. 88 In practice, not even the minimal require ments of Uruguay's commitment law are enforced.

1. Lack of criteria for commitment

Article 15 of the law of Assistance to Psychopaths provides generally that involuntary commitment by medical order is authorized only for "treatment purposes."89 While the law limits involuntary commitments to patients certified as "mentally ill," there is no further definition of what constitutes "mental illness." No other substantive criteria are required for most involuntary commitments.9°

The commitment law of Uruguay fails to contain the MI Principles' minimum substantive standards that would limit involuntary commitment to individuals who are dangerous to themselves or others,91 or to individuals who, because of severe mental illness, require treatment that cannot be provided outside the setting of a psychiatric hospital.92 In addition to its failure to define "mental illness," the law does not require that a determination of mental illness "shall be made in accordance with internationally accepted medical standards. "93

Despite its weaknesses, the commitment law of Uruguay might prevent the hospitalization of half the patients now in Uruguay's public psychiatric institutions if the law were actually enforced. As described in section A-2 above, authorities estimate that one-third to one-half of the population of the Colonias are placed in the institution because of mental retardation and not mental illness. A range of individuals now hospitalized because of epilepsy, alcoholism, old age, or petty criminal behavior would be excluded from institutions by law if they are not mentally ill. "Social patients," who by official accounts constitute approximately half the total patient population, are hospitalized because "they have no place to go" and not for the purpose of psychiatric treatment as required by Uruguay's commitment law. Thus, full enforcement of Uruguay's commitment law would require and end to the practice of detaining "social patients."

2. Lack of procedural protections

Commitment procedures under the law of Assistance to Psychopaths fail to provide protections against improper commitment both as a matter of law and as a matter of practice.

a. Commitments under Uruguay law

Under Uruguay's law, individuals may be subject to involuntary commitment in four ways, by (1) medical certification,94 (2) emergency medical commitment,95 (3) emergency police commitment,96 or (4) judicial order.97 According to institution authorities, the great majority of patients are admitted by medical certification, and only ten to fifteen percent are admitted by judicial order.98 Only one to two percent of patients are reported to be admitted to the institution as voluntary patients.

Three of the four methods of commitment (except judicial commitment, which is described further in section C-4, below) entail a certification process which may include approval by the institution medical director, independent physicians, family or police (these three methods of commitment are described here as "commitment by certification"). In all three forms of commitment by certification, the admitting physician must notify an "Inspector General of Psychopaths"99 and a judge within twenty-four hours. Neither the Inspector nor the judge are required to act on this notification.

Since there are no substantive criteria for determining who can be committed in most cases (except "mental illness" and "for the purpose of psychiatric treatment"), the certification process under the law of Uruguay requires only the consent of the person providing certification. There are no limits on the discretion of the individual providing consent.

"Medical certification," the most common way individuals are committed to psychiatric institutions (and the procedure with the fewest protections), requires consent of the receiving physician at the hospital, and two physicians who must agree that the individual is "mentally ill." In addition, there must be consent by the patient's closest relative, legal representative, or an adult living with the patient. Since medical certification is always an option, any additional protections created by other forms of commitment can be circumvented

Not surprisingly, the three methods of commitment by certification in the 1936 mental health law of Uruguay do not provide the procedural protections contemplated by the MI Principles. Although a court must be "notified" within twenty-four hours of any involuntary commitment, 100 there is no right to a review of commitment by a "judicial or other indepen dent or impartial body."101 None of the methods of commitment by certification provide an individual subject to involuntary commitment with a right to "appeal to a higher court." 102 Nor does the individual have the right to counsel,103 or to "attend, participate, or be heard personally in any hearing. "104

The Ml Principles do not provide relatives or legal representatives with the right to commit a psychiatric patient, and international law generally does not allow one person to waive another individual's rights. In lieu of rights provided to the person subject to commitment, however, the rights that Uruguayan law delegates to family members could provide protections against some improper commitments. Even so, not even this minimal protection is consistently enforced. Many family members reported to MDRI that they were never asked permission when their relative was committed. Some family members who were asked to consent said that they considered it a formality - they were provided with no information about the commitment and they never believed they actually had a choice.

One mother reported being able to prevent commitment by refusing to consent, but she said that this proved to be a difficult experience. When she refused, psychiatrists tried to go around her by asking other members of the family to authorize commitment. According to the mother, the institution psychiatrist told other relatives that her judgment was impaired due to stress and exhaustion. Despite this, none of the other relatives agreed to provide authorization, and the commitment did not go forward.

b. Inspector General of Psychopaths

One of the potentially most important protections under the law of Assistance to Psychopaths, is an office called the "Inspector General of Psychopaths" (lnspecci6n General De Psic6patas).105 The Inspector is intended to provide independent oversight of the commitment process and to monitor the enforcement of the mental health laws generally.106

The admitting physician at a psychiatric institution must notify the Inspector within twenty four hours of any commitment and must provide a certificate explaining the patient's symptoms and conditions. 107 The Inspector may help family members who seek release of a relative from a psychiatric institution by bringing a case to the attention of judicial authori ties.108 The Inspector must keep a general registry of everyone civilly committed.109 In order to monitor the enforcement of mental health laws, the Inspector may conduct unannounced visits to psychiatric institutions, send warnings to institutions about improper commitments, or notify courts of potentially criminal wrongdoing.110

Despite these intended protections, the practical value of this law has been limited. From the early 1970's until 1992, the position of Inspector of Psychopaths was vacant.111 In October 1992, one month before the visit by the MDRI team, the position was filled for the first time. The new Inspector, serving as an independent ombudsman, could potentially provide important protections to patients subject to civil commitment. Yet the current law establishes significant limitations on the Inspector.

The most important limitation on the value of the Inspector is that patients do not have a right to review of commitment by the Inspector, nor do they have a right to participate in the review in any way. The investigation of any particular case is now entirely up to the Inspector's discretion. This limitation is particularly serious, given the lack of a right to a hearing by an independent review body under the commitment law. The power of the Inspector is also limited by the weakness of the underlying commitment law that the Inspector is empowered to enforce.

The new inspector has an enormous task before him to make up for the years of improper commitments. 112 The Inspector reported to MORI that his first major project would be to modernize and computerize the psychiatric register, which contains information about every person who has ever been committed to a psychiatric hospital.113 In addition, the Inspector said that he planned to institute a new system to require institutions to obtain informed consent of families before providing ECT.

The Inspector stated that, within a year, he intends to review every psychiatric commitment in the country of more than sixty days, beginning with commitments at private psychiatric facilities. The Inspector's method for a review of commitment, which he demonstrated while a member of the MORI team was in his office, is to telephone the director of a psychiatric institution and ask about the well-being of a particular patient. If the director states that the patients is present and still mentally ill, the review is complete. While this method of review may help up-date the psychiatric register, it provides almost no human rights protections to the patient: The current method provides no opportunity to review whether an individual meets substantive criteria for commitment, it provides patients with no due process protections or opportunity to present their views or concerns, it provides no independent check on the authority of psychiatric institutions, and it provides the Inspector with no independent information about the conditions and possible abuse of psychiatric patients.

The Inspector acknowledges also that there is a problem of patient access to his services. After two months in office, very few, if any, patients were aware of his office, and no patient had yet contacted him with a problem. In response to this situation, the Inspector also stated that he would insist that all private psychiatric institutions provide patients with access to tele phones. The Inspector told MORI that any private institution that does not provide patients with access to a telephone would have its license revoked within a few months.

3. Indefinite length of commitment

The Law of Assistance to Psychopaths provides only indefinite commitment and places no practical limitations on the discretion of medical authorities to retain a person in an institution. Most patients may be discharged only when the treating physician determines that there is no more need for treatment. 114

The law further provides that individuals who have at any time been subject to "restraint of liberty" within an institution can only be released when "they are no longer dangerous. "115 The law does not provide a right to discharge, however, to a patient who is no longer dangerous.